Particle/Anti-Particle Annihilation

Matt Strassler [March 25, 2012]

The annihilation of particles and anti-particles gets a lot of press — it sounds mysterious and scary and exciting and makes its way into lots of science fiction — but this bread-and-butter process at the heart of particle physics creates a lot of confusion. In this article I want to start demystifying it a bit, by describing a few of the basic rules that determine whether a particle and anti-particle of one type, if they come close together, can turn into a particle and anti-particle of another type. This isn’t the full story of particle/anti-particle annihilation, but it will get you started.

What are anti-particles? I wrote an introductory article about anti-particles here. For our purposes today, this is what you need to know. In a world like ours (with quantum mechanics and Einsteinian relativity) it is a mathematical theorem that every type of particle has a corresponding anti-particle, with exactly the same mass. Actually, it’s not just a theorem: for all known particles the anti-particle has been observed experimentally, so we don’t need to have a debate about it.

(Note: When I use the term `mass’ on this site I always mean the quantity that long ago was sometimes called a particle’s `invariant mass’; in accordance with modern particle physics practise, I never use the concept of `relativistic mass’ on this site. All electrons have the same mass; all photons are massless; this is true no matter how much energy they have and how they are moving.)

However, for some particles the anti-particle and particle are the same: the antiparticle of a photon (a particle of light) is a photon. The same is true for the Z particle and the Higgs particle (assuming the latter exists.) On the other hand, the electron, which has negative electric charge (by definition), has an anti-particle called the “anti-electron” or “positron,” which has positive electric charge. [Do not confuse the positron with the much heavier and more complex proton!] This is true for most of the known particles: the muon has an anti-particle called an anti-muon; the up quark has the up anti-quark; the anti-particle of the positively charged W particle is a negatively charged W particle.

Now, a fact: if I put a particle and an anti-particle together, almost all their properties cancel. For instance, the electric charge of a muon (a heavy cousin of the electron) plus the electric charge of an anti-muon equals zero; the former is negative, the latter positive, but they are equal in size and so they cancel perfectly. The only things that don’t cancel are their masses and energies. Actually, that statement’s a bit tricky. Mass isn’t “conserved”; we’ll see in a minute that mass can appear or disappear, which is really good for particle physics. The only thing that is definitely going to stick around is energy. Energy is conserved: however much you start with, you will end with the same amount. If these things sound obscure, stay tuned; we’re going to watch them play out.

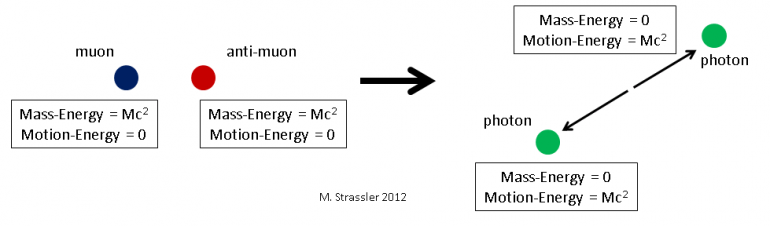

1. Muon and anti-muon turn into two photons

Suppose I have a shoebox that has nothing in it except a muon and an anti-muon that are just about stationary. Then the energy inside the box is just about equal to the mass-energy of the muon plus the mass-energy of the anti-muon. [I'm saying "just about" because I'm oversimplifying by ignoring the electric field between the muon and anti-muon; but trust me that this is a tiny effect of one part in 10,000 that we can ignore for current purposes.] Let’s call the mass of the muon “M”; then the mass-energy of the muon is M c2, and the same is true for the anti-muon; and both have zero momentum since they aren’t moving. So the total energy E and momentum p in the box is initially just about

- Einitial = 2 M c2

- pinitial =0

Meanwhile everything else in the box is zero: the total electric charge is zero; the total angular momentum is zero; there aren’t any other things that are non-zero. Just the energy. And the mass, but they’re related.

Because almost everything cancels, it is often possible for a particle and its antiparticle to transform, through the action of one of the four known forces, into another particle and its antiparticle. For instance, the muon and the anti-muon could transform into a photon and a second photon (remember, the photon is its own anti-particle.) The photons will both have some energy; how much exactly? Well, the two photons are similar so they will have the same energy, and since energy is conserved the total final energy will be the same as the total initial energy, so

- Ephoton = 1/2 Efinal = 1/2 Einitial = M c2 = Emuon

Wow. Notice what amazingly cool thing has just happened: we started with massive particles, each motionless and so having no motion-energy, and having mass-energy M c2. But we ended up with two massless particles, with no mass-energy, but with motion-energy equal to the muon’s mass-energy: M c2. See Figure 1.

Fig. 1: A stationary muon/anti-muon pair, with only mass-energy, can turn into two photons, which have only motion-energy.

The photons will also each have momentum. But the momentum of the two photons will be opposite each other, and the total final momentum will add up to zero.

- pfinal = pinitial = 0

Notice that energy is conserved, momentum is conserved, but mass is not: the final mass is zero, even though the initial mass is 2 times M.

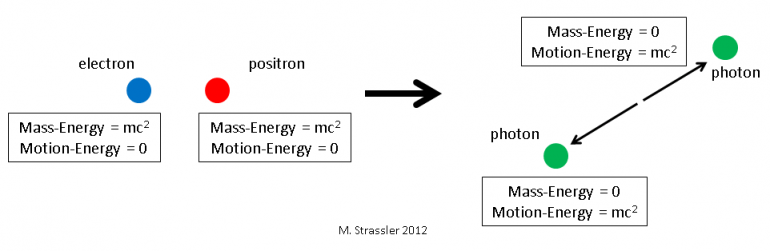

2. Muon and anti-muon turn into an electron and anti-electron

The basic reaction

- particle 1 + anti-particle 1 → particle 2 + anti-particle 2

isn’t the only possible process that can happen when a particle and anti-particle annihilate, but it is a very common one. Let’s look at another option for particle 2.

Fig. 2: If instead the muon/anti-muon pair turn into an electron/positron pair, the electron's energy will be the same as that of the muon, but it will be split, most of it motion-energy but with a small amount of mass-energy.

Instead of becoming two photons, the muon and the anti-muon may instead transform into an electron and a positron (an anti-electron), as in Figure 2; both the electron and positron have the same mass, which we can call m. (The electron mass m is about 200 times smaller than the muon mass M.) It is random chance (but with probabilities determined by quantum mechanics’ equations) that determine whether a given muon and anti-muon will turn into photons or into an electron/positron pair.

Exactly the same logic we used above leads to the same conclusion; by symmetry, the electron and the positron, which have equal mass, will emerge with equal energy, and by conservation that energy must be the same as the initial energy of the muon

- Eelectron = Epositron = 1/2 Efinal = 1/2 Einitial = M c2 = Emuon

So this is a little different; we started with massive particles, each motionless and so having no motion-energy, and having mass-energy M c2. But we ended up with two massive particles, each with a bit of mass-energy m c2 and a lot of motion-energy, with the electron’s total energy equaling the muon’s mass-energy M c2. And again, for the same reason as above, the momentum of the electron cancels the momentum of the positron:

- pfinal = 0

And of course their electric charges cancel too; there was no electric charge in the box before the transformation, and there is none after. Again, energy is conserved, momentum is conserved, charge is conserved, but mass is not; the initial mass was 2M, the final mass is 2m.

Fig. 3: The annihilation of an electron/positron pair to two photons is in exact analogy to Figure 1, except for the replacement of the muon mass M by the electron mass m.

3. Electron and anti-electron turn into two photons

An electron at rest and a positron at rest can turn into two photons, just as a muon and anti-muon can. In fact we can do the whole calculation just by going back to the muon case, and in all the discussion and the equations replacing M by m. There’s really no difference (compare Figure 1 and Figure 3.)

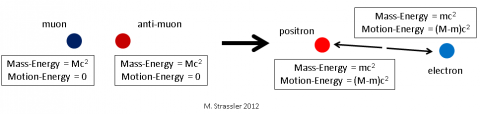

4. Can an electron and anti-electron turn into a muon and anti-muon?

No. And Yes. What I will explain in a moment is that the answer depends on how you ask the question:

- No, if the electron and positron are initially at rest. There isn’t enough energy to make a muon and an anti-muon, so the process cannot occur.

- Yes, if the electron and positron have large amounts of motion-energy and hit each other head on. As long as there is enough energy to make a muon and anti-muon, then this process can occur.

Ok. First, let’s convince ourselves that if the electron and positron aren’t initially moving — if they have no motion-energy to start with — there is no way they can turn into a muon and anti-muon. The logic is terribly simple; all we have to do is go back to the previous case where we considered a muon and anti-muon turning into an electron and a positron, and everywhere exchange muon for electron, anti-muon for positron, and M for m. This gives us

- Emuon = Eanti-muon = 1/2 Efinal = 1/2 Einitial = m c2 = Eelectron

But this equation is impossible! A muon has mass-energy M c2 plus its motion energy, which is positive. And M is bigger than m. This gives us a contradiction:

- Emuon = M c2 + motion-energy ≥ M c2 > m c2

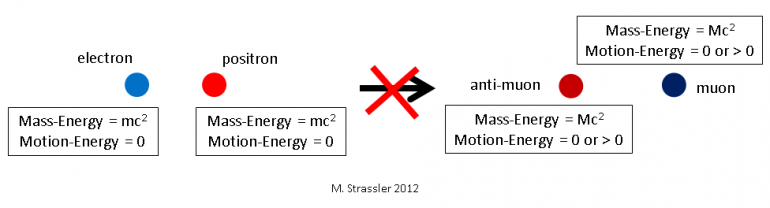

In short the muon’s energy cannot equal m c2, as the conservation of energy (the second-to-last equation) would demand, because M is larger than m. Faced with this contradiction, we must conclude: this process cannot occur (Figure 4.)

Fig. 4: A stationary electron/positron pair cannot annihilate to a muon/anti-muon pair because the muon has larger mass and so there is insufficient initial energy.

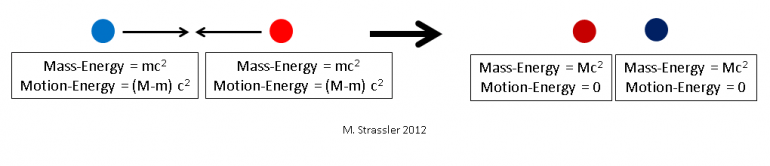

However, the very way that this effort fails reveals how it may be acheived. For we need not consider electrons and positrons that are initially at rest. Let’s accelerate them — speed them up to near the speed of light, so that their motion energies are very large and their total energies (mass-energy plus motion-energy) are much larger than m c2. To keep things simple, let’s imagine we’ve made their initial energies exactly equal to M c2 ; then the total initial energy in the box is 2 M c2, and so for the process to occur the conservation of energy demands

- Emuon = Eanti-muon = 1/2 Efinal = 1/2 Einitial = M c2 = Eelectron

which is no longer in contradiction with the requirements of the previous equation, Emuon = M c2 + motion-energy ≥ M c2 > m c2. In fact, the electron and positron’s energies are in this case just barely large enough to a make a muon and an anti-muon at rest (Figure 5.)

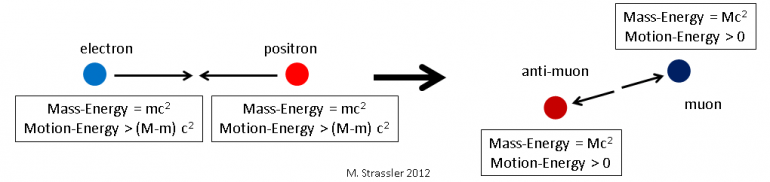

Fig. 5: If the electron and positron (left) collide with sufficient motion energy, that energy can be converted into the mass-energy of a heavier and stationary muon/anti-muon pair (right).

If we make the electron and positron’s energies even bigger, then they can still make a muon and an anti-muon. The excess energy will go into motion-energy of the muon and anti-muon; see Figure 6.

And notice again that mass is not conserved, even though energy is. In this case, the mass has gone up, from 2m to 2M. This is really important for particle physics!!! This is one of the main techniques that we use for discovering new particles; we smash a particle and its anti-particle together with very high motion-energy, in hopes that they will turn into a heavy particle that we’ve never before observed, along with its anti-particle.

Summary

- A particle and its anti-particle that are stationary can annihilate to make a particle and its antiparticle as long as the initial particle is heavier than the final particle.

- A particle and its anti-particle that are stationary cannot annihilate to make a particle and its antiparticle if the final particle is heavier than the initial particle.

- A particle and its anti-particle that are moving relative to each other can annihilate to make a heavier particle and its antiparticle if they have sufficient motion-energy.

- If the mass-energy plus the motion-energy of the particle equals the mass-energy of the heavier particle, then the heavy particle and anti-particle pair will be produced stationary.

- If the mass-energy plus the motion-energy of the particle is greater the mass-energy of the heavier particle, then the excess energy will go into motion-energy of the heavy particle and anti-particle pair.