4. Lesson 18:

Special Relativity, 4¶

Einstein’s Mass and Energy

What’s Coming:

Here we go. The T-shirt equation. Nothing is the same after this fourth of Einstein’s 1905 papers…that one that said \(m=\dfrac{E}{c^2}\). We’ll develop it without calculus (although if you want to see a full derivation, it’s included for those with that background). Energy now simplifies! Mass becomes interesting! Particle collisions become understandable! Matter gets made! And I get my white board on the Big Bang Theory!

4.1. A Little Bit of Minkowski¶

Fig. 4.1 Hermann Minkowski

1864-1909

¶

“It came as a tremendous surprise, for in his student days Einstein had been a lazy dog… He never bothered about mathematics at all.”

The story of Hermann Minkowski is both engaging and sad. He grew up in Königsberg, Germany after some time in Russia, to a middle-class business family. His mathematical skills were apparent in high school and he entered the University of Königsberg where he stayed through his PhD degree, winning a prestigious prize at the age of 17 for a solution to a challenge problem issued in European mathematics. Mathematicians like to do that sort of thing.

In 1887 he was recruited to the University of Bonn where he taught for seven years and returned to his alma mater, the University of Königsberg, where he stayed for two years before he was appointed the chair of mathematical physics at Eidgenössische Polytechnikum Zürich in 1894. He married in 1897 and had two daughters, the second in 1902.

Fig. 4.2 Hermann Minkowski during the last year of his life.¶

That was a big year for him professionally as well as David Hilbert created a chair for Minkowski at the center of European mathematics at the University of Göttingen. It was there that he developed the ideas of space and time that outlived him and set the path for a firm foundation of Special Relativity and motivated the approach to the General Theory of Relativity. This mathematization of physics was not originally welcome to Einstein, but he grew to embrace it. In fact, in some ways it was Minkowski’s style and his skill that changed the relation of physics and mathematics to the present day.

Morris Kine in a review wrote, “A key point of the [Minkowski] paper is the difference in approach to physical problems taken by mathematical physicists as opposed to theoretical physicists. In a paper published in 1908 *Minkowski reformulated Einstein’s 1905 paper by introducing the four-dimensional (space-time) non-Euclidean geometry, a step which Einstein did not think much of at the time. But more important is the attitude or philosophy that Minkowski, Hilbert, Klein, and Weyl pursued, namely, that purely mathematical considerations, including harmony and elegance of ideas, should dominate in embracing new physical facts. Mathematics so to speak was to be master and physical theory could be made to bow to the master. [my emphasis] Put otherwise, theoretical physics was a subdomain of mathematical physics, which in turn was a sub-discipline of pure mathematics.”

That Minkowski embraced the implications of Special Relativity is a delicious irony as he was Einstein’s mathematics professor in Zurich and his opinion of him was right in line with that of the other faculty:

“Oh, that Einstein, always cutting lectures… I really would not believe him capable of it.”

It was Minkowski who merged space and time into a single “Spacetime” continuum – a mathematical space, but importantly, a model of how the universe is really stitched together. That’s the “Spacetime” in Quarks, Spacetime, and the Big Bang. Below we’ll visit some of “Minkowski Space” and here’s a preview from his notes. Remember the plot at the top.

Fig. 4.3 MARGINCAP¶

This work he did in 1908. While it was well-received, it was a semi-popular lecture that he gave that was the stimulus to many to take Relativity seriously. Ask Mr Google about “views of space and time” and he’ll reward you with 3.5 billion hits:

“The views of space and time which I wish to lay before you have sprung from the soil of experimental physics, and therein lies their strength. They are radical. Henceforth, space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.”

To the shock of the community and dismay to his many friends around the world, Minkowski died suddenly at the age of 44 due to a ruptured appendix.

4.2. Working Our Way toward Relativistic Energy¶

At the end of the last lesson, we crept up on the notion that the speed of an object being pushed at a constant value changes, but not linearly, so that it never exceeds the speed of light. Here’s a cartoonish sketch of that summarizes what seems to be going on.

What we had is a constant force pushing on a mass, creating a momentum, and so a speed.

Fig. 4.4 MARGINCAP¶

Now, let’s compare the Newtonian experience (rather, assumptions) with the relativistic experience.

Fig. 4.5 MARGINCAP¶

In (a) we have the Newtonian notion of a fixed mass and an unlimited speed and so an unlimited momentum. In (b) we have the relativistic situation in which we know that the speed is limited and there’s no limitation on the momentum. So how does that happen? The mass must be unlimited. Not constant, as in the Newtonian definition.

Fig. 4.6 MARGINCAP¶

Mass is going to become a very strange thing.

Remember that mass for Newton was problematic. It was a definition that was circularly defined in terms of density. How you measure it presumes that you know how to measure acceleration and force…without the mass. Circular. Relativity is the opening salvo against the naive notion of mass from Newton and we’ll see that with the Higgs Boson discovery in 2012, our ideas of mass changed again…to be even more strange.

4.2.1. Relativistic Momentum¶

Momentum is still:

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

But by now you know the song: that numerator and denominator depend on the frame and so a new kind of momentum – relativistic momentum – is required. I’ll just state it here:

Looks familiar, but there’s the \(\gamma\) function, which tends towards \(1\) when \(u\) is very small, so we get back “regular” momentum.

4.2.2. An Einstein Thought Experiment¶

Let’s follow one of Einstein’s typically imaginative thought experiments that he suggested in his original 1905 fourth paper. The T-shirt equation paper. In order to appreciate it, I need to tell you something that he postulated in his first 1905 paper that was on light quanta – that light consists of little particles that he called “quanta” and which were named “photons” in 1925 by someone else. The thing that we need from this idea (which we will talk about a lot later) is that these little particles carry momentum.

So inside a box is a source of light (photons) at the left and an absorber of photons on the right. We start with the box sitting still, minding its own business.

Fig. 4.7 MARGINCAP¶

Now the bulb is turned on and light begins to stream away from it, that is, photons carry momentum to the right.

Fig. 4.8 MARGINCAP¶

So momentum is now imbalanced to the right, unless the box itself moves to the left with the same, but oppositely directed value of momentum. It recoils.

So from the outside, you see this box suddenly begin to lurch to the left! Then, when the photons strike the absorber on the right-hand side of the box (perfectly absorbing so that there’s no reflection)…the box suddenly stops!

Fig. 4.9 MARGINCAP¶

Einstein analyzed this event and showed that the center of mass of the box rearranged itself and that therefore the photon has to behave as if it has a mass.

Seriously. In the first paper (and every other paper anyone has written since!) the photon is an object with zero mass. And yet, this simple head-experiment concludes that the light has an energy – even Maxwell knew about electromagnetic waves carrying energy. But since light has momentum, we must interpret the situation to suggest that the photon’s energy leads to a second conclusion that suggest that energy is mass-like. That’s a lot to swallow.

4.2.3. Approximating Functions¶

There are a number of ways to get to the T-shirt equation and most require calculus which I’ll not do in QS&BB. I want to sneak up on it with a plausibility argument, rather than a direct proof. In @ref(#lessonmath) I introduced the notion of approximating a function’s shape by successively adding together a string of functions, each one getting you closer and closer to the full function. This was Newton’s idea. What I did in that lesson was look at the function

and showed that it can be represented as the series

the dot-dot-dot means that this progression continues to an infinite number of terms and that when you add them all up you get back \(\dfrac{1}{1-x}\). Almost magical.

Here’s what that looks like:

Fig. 4.10 MARGINCAP¶

Notice a couple of things. First, the full function is the top, bold red curve. Second, notice that each curve in the series does indeed get closer and closer to the desired function. It’s going to take a lot of them to get there – an infinite number of them.

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

Finally, notice that for small \(x\), say below \(x=0.2\) the first two terms, \(1+x\) do a pretty good job. So in practical terms, if you’re sure that your \(x\)’s are going to be less than that value you don’t have to use the whole function, you can get by with just \(1+x\).

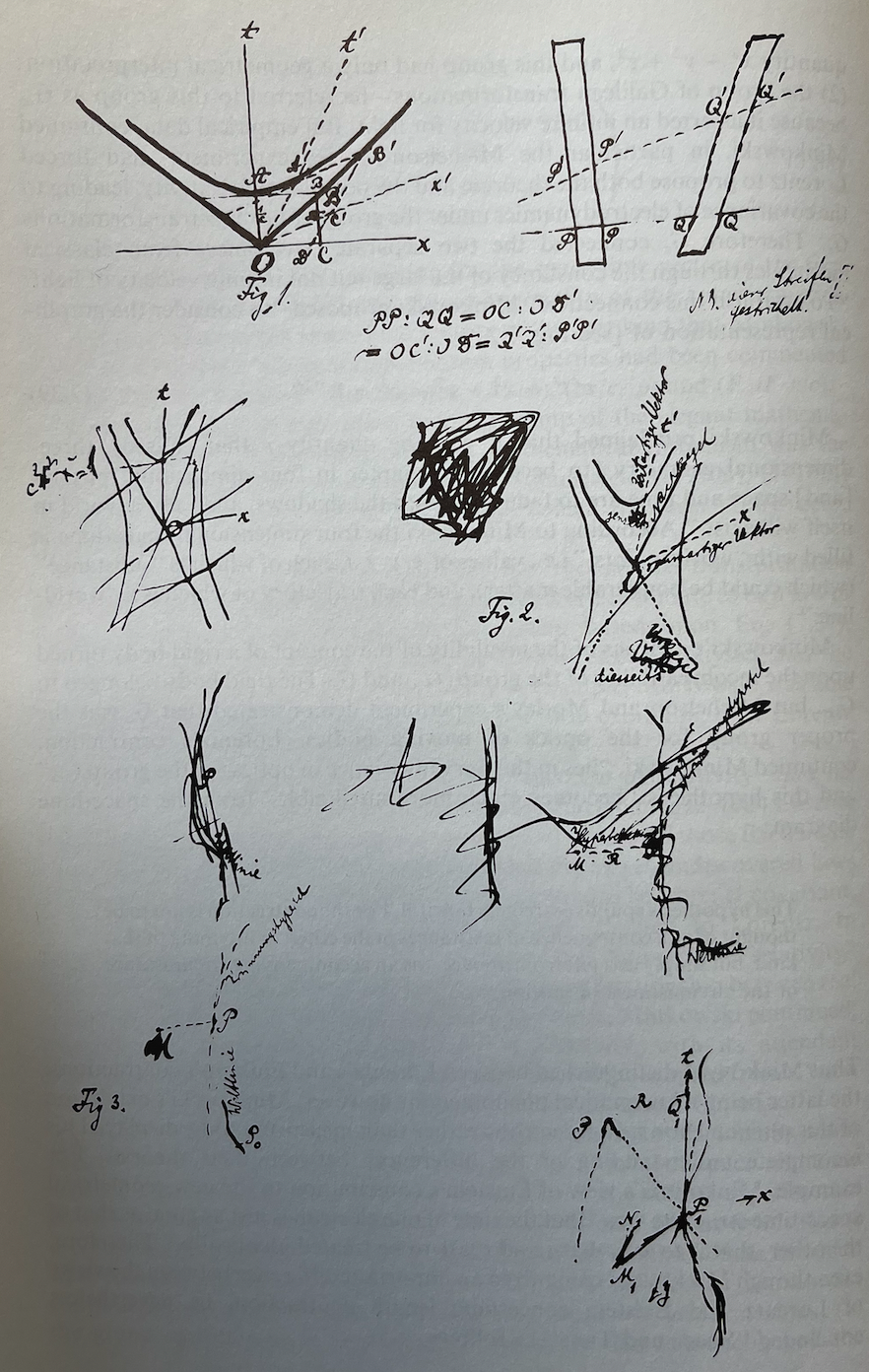

So, with that reminder…we have a function that’s in every relativistic equation, namely, \(\gamma\):

and maybe you know where I’m going. We can indeed express this function in an infinite series and it would be:

Here it is plotted:

Fig. 4.11 MARGINCAP¶

where I’ve emphasized only the first two terms. Again, if we are only interested in very low \(\gamma\)’s we can get away with just the first couple of terms and we’ve done a pretty good job of approximating the whole relativistic gamma function. Knowing that “regular life” is pretty Newtonian, that part of the gamma function should do a pretty good job for barely relativistic situations.

4.2.4. Einstein’s Energy Equation, Through the Back Door¶

Let’s play with that term now and see if we can gain some insight.

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

This is a pencil-out activity. Look at the first two terms in the \(\gamma\) expansion:

Look at the second term. This is really suspiciously like the classical kinetic energy form, \(K=\frac{1}{2}mv^2\), right? Let’s run with this and see what happens. In order to nudge it along, let’s multiply by \(m\) and by \(c^2\). That would do it, right?

By now we’re used to the idea that slow objects’ modeling are an approximation to the complete relativistic objects’ form. We’re obviously in a slow-ish format here by keeping only the first two terms of the \(\gamma\) function. So we isolated the “regular” kinetic energy piece on the right and so we also know that whatever is left in the other two terms are also energy terms:

\(m\gamma c^2\) is some kind of energy

\(mc^2\) is another kind of energy

\(\frac{1}{2}mu^2\) is the familiar kind of energy of motion, kinetic energy

This is a fundamental change in how we think about energy. What we’ve created through the back door is a new kind of energy:

Total energy of an object \(=\) its energy of mass \(+\) its energy of motion

Even if the object were not moving, it would still have energy in this picture. In fact, all of energy can be described by this little formula - potential energy, chemical energy, nuclear energy, electromagnetic radiation energy, the whole shebang energy.

Here’s our accounting:

\(E_T =\) total energy of an object \(= m\gamma c^2\), first formulation

\(E_m =\) mass energy of an object = \(mc^2\)

The T-shirt equation:

Fig. 4.12 MARGINCAP¶

I’ve left out the kinetic energy here because my back door approach to this was for non-relativistic motion, so our original \(\frac{1}{2}mu^2\) term was relevant. But the fully relativistic kinetic energy is different and we can simply derive its form from what we’ve got by generally calling it “\(K\).”

So our inventory is:

\(E_T =\) total energy of an object \(= m\gamma c^2\), first formulation

\(E_m =\) mass energy of an object = \(mc^2\)

\(K =\) energy of motion \(=\) \(mc^2(\gamma -1)\)

\(p = m\gamma u\) \(=\) relativistic momentum

Have a look at a deeper explanation 1 🖋 📓

With a little bit of algebra, we can write our second form of the total energy:

and we can understand Einstein’s little game of the box with the light.

Please study example 1 🖋 📓

Remember, he had to conclude that if light carries momentum, which Maxwell knew, then it has to behave as if it has a mass, which is not strictly true. In Equation totalE we see how that works. If light quanta are massless, and they are, the total energy is not zero, it’s:

We can see this in a visual way using Pythagoras’ theorem since

Fig. 4.13 MARGINCAP¶

For different kinds of objects, as the mass leg gets smaller and smaller, the hypothenus gets closer and closer to the horizontal leg.

Note

So what does one do when visiting a friend at UCLA who was the Science Advisor for the television program, The Big Bang Theory? And he hands you a marker and your own on-air whiteboard? Why you tell the world how to expand the gamma function. That’s what.

Fig. 4.14 MARGINCAP¶

Please study example 2 🖋 📓

4.2.5. Two Things to Worry About¶

There are two issues buried inside of the general total energy relation that merit attention:

Note

Thing 1. Remember that Einstein started his discussion with his quantum idea, which we’ll have to wait to learn more about. But I’ve already told you that the photon – the quantum of light – has no mass. Notice that this equation for energy accommodates that.

which is precisely what he suggested was the case for a single quantum of light in his first 1905 paper.

and

Note

Thing 2. Remember that a square can have two roots, one positive and one negative. What about the total energy squared?

What are we to make of a negative energy? Stay tuned. But this plagued efforts to create a quantum mechanics that was relativistic.

Please study example 3 🖋 📓

4.2.6. Remember How We Got Here?¶

I started worrying about inertia in the last lesson when we found that a constant force applied to a massive object would result in a constant acceleration (our example was \(g\)) but that the speed of that object would increase at a slower and slower rate, never passing \(c\). Our notion of relativistic mass is a way to think about why that is the case. Since here, \(m_R = \gamma m\) it increases with speed through the relativistic gamma function:

Remember to push Run:

So if you’re fortunate enough to be moving at 80% of the speed of light, your mass as viewed from a Home frame would be about 1.75 times your rest mass as you would “feel” in the Away frame. Food for thought, if you’re a particle physicist. Stay tuned.

Particle accelerators? They operate in the high-end of gamma…here’s a useful example of the gamma region of interest:

Remember to push Run:

Please answer question 1 📺

4.2.7. What Is Mass, Anyway?¶

Einstein’s fourth, less than three page 1905 paper in November, was entitled, Does The Inertia Of A Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content? and he worked out (with different names for the variables):

“If a body gives off the energy E in the form of radiation, its mass diminishes by \(m=\dfrac{E}{c^2}\).” And he closed with, “It is not impossible that with bodies whose energy-content is variable to a high degree (e.g. with radium salts) the theory may be successfully put to the test. If the theory corresponds to the facts, radiation conveys inertia between the emitting and absorbing bodies.”

This. Is an extraordinary idea. Any object with a mass has a special energy solely associated with that mass. “Mass-energy” is a common term for this and captures the notion succinctly. But “energy-mass” is also applicable as we saw for the massless photon in the box! It had energy, but that energy conferred on the photon features that dynamically played the role of a mass.

It’s often said – INCORRECTLY! – that mass can be converted into energy. Mass IS energy and energy IS mass. We can convert the units, but not the actual substance. The best analogy I can think of is currency.

Today, $1 is convertible into 0.83 EURO. If I were to go into a shop in the Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam and purchase a magazine I could pay at the counter in dollars or I could pay in euros – both are readily acceptable in that airport. Their values are identical and indeed, colloquially we can convert dollars into euros and we would see visually the two currencies are represented by two different kinds of paper and coins. The economic value however is identical and the passage of one unit into the other is accomplished by a single conversion factor: 0.83. If I have 10 EURO, I can convert that into dollars:

The conversion of mass and energy units functions the same way. The value of mass-energy is identical, and the conversion of units is accomplished by a single conversion factor as well: from \(E=mc^2\), the conversion is

(in the MKS system). A very big number! If I have a 10 kg object, I can convert that into Joules:

The size of this is hard to wrap your head around. The amount of energy trapped in even tiny masses is enormous.

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

But there’s more to this than just the identification of energy with mass and vise versa. There’s also the interpretation of mass as not constant. From a silly little rearrangement from above:

So, another way of looking at the total energy of an object is to combine its \(E_m = mc^2\) with \(K\) to get:

We’ve now got two “kinds” of mass: what we’ll call the “relativistic mass” and the “rest mass.” The latter is the mass of an object in its own rest frame, like proper time is the time that you read from the watch you’re wearing in your own rest frame. That we’ll call:

The former is what’s sometimes called the Relativistic mass:

The Relativistic mass changes as the speed of a frame changes with respect to a Home observer. By a factor of \(\gamma\).

In our Home and Away notation, the masses are related as:

Note

This is a controversial point. While there is no difference between two interpretations of mass, professional physicists do not use “relativistic mass” preferring to keep the idea of mass a constant quantity regardless of motion and deal exclusively with the total energy, \(E_T\). I think that for our purposes, the relativistic mass is a very nice interpretation which carries a lot of insight along with it. So don’t tell my friends, okay?

4.2.7.1. Momentum In Relativity¶

Remember that I introduced momentum for relativity as if it’s a definition. That’s not strictly the case, and again, it’s a calculus derivation so it’s not appropriate for this text. But we can circle back and retain our original idea of momentum as

by using the relativistic mass in this relation: \(m_R = \gamma m\) where \(m\) is the rest mass. Now we get the originally postulated relativistic momentum:

Remember, that conversion factor is enormous. We need an apple.

Fig. 4.15 MARGINCAP¶

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

Remember that in this beloved example, our table is 1 meter above the ground and the apple has a mass of 0.1 kg. The kinetic energy when it hits the ground is 1 J if we approximate \(g \approx 10\) m/s\(^2\). What is the energy trapped inside of the apple’s mass in comparison?

…essentially \(10^{16}\) times its motion energy as it hits the floor.

Let’s go to an old-time particle accelerator – one in which protons are accelerated to only 95% of the speed of light.

Please study example 4 🖋 📓

Please answer question 2 📺

Please answer question 3 📺

From this point on, when I refer to “mass,” I’ll mean the relativistic mass, \(m_R\). If I mean the mass of an object inside of its own rest frame, I’ll explicitly refer to the “rest mass,” \(m\).

4.3. The Rubber Meets the Road: Particle Creation and Potential Energies¶

In our lesson on energy we learned to represent energy conservation as

Kinetic plus potential energies before…must equal kinetic plus potential energies after some event. That potential energy term was always a little squirrelly – like it was added to make things work.

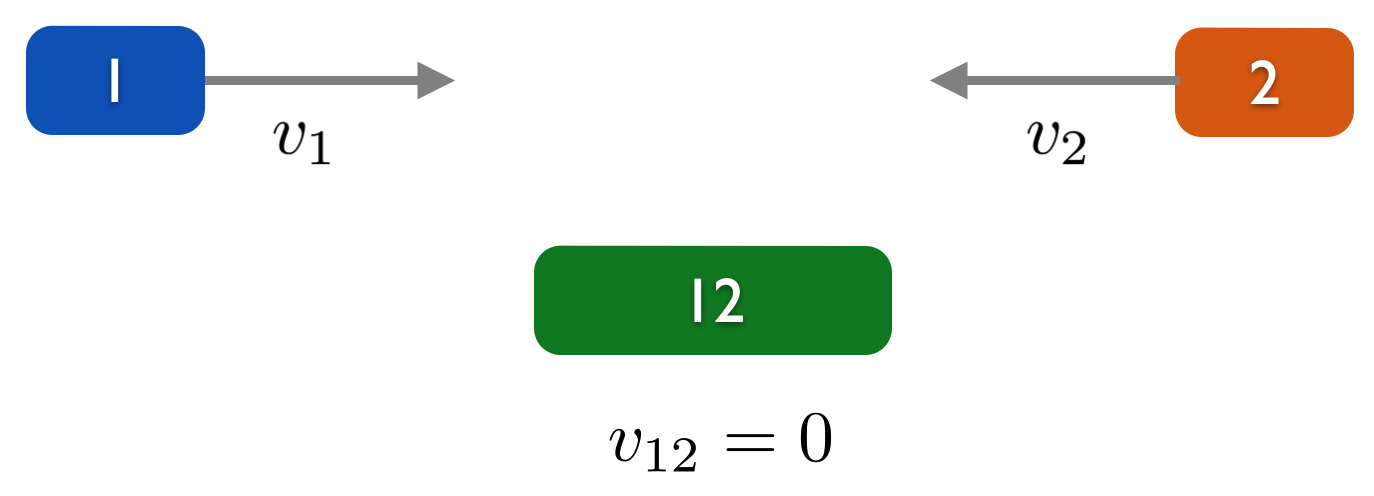

Let’s imagine a football tackle. Player \(1\) runs at player \(2\), tackles him, and they stick together forming a new, single object “\(12\).” The masses of the two players are identical and their speeds are equal.

Fig. 4.16 MARGINCAP¶

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

What would a physics student have calculated in 1904? First, she would have said that momentum was conserved:

And she would have conserved energy:

which doesn’t make any sense. At this point her professor would mumble about energy lost in heat, the springiness of the two objects causing compression and then a release of that compression by heating and moving the air, which we’d hear as sound…and so on and so on. That is, this completely inelastic collision would conserve total energy, but we would have written it like this:

Now let’s suppose it’s early 1906 after Einstein’s realization, and the collision is a for relativistic football tackle.

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

In Special Relativity, we would now write:

Total energy is still conserved, but how it arranges itself between energy of mass (\(E_m\)) and energy of motion (\(K\)) changes.

Now, momentum is still conserved, so the combined objects, 12, stop dead (no pun intended…but if it’s relativistic, they’re moving pretty fast!). That means that \(K_{12 (\text{after})}=0\) and we now have:

Let’s rearrange this a little:

which is different from the 1904 calculation. Remember, there we found that

and that’s now not the situation. In fact,

and so

The combination of the two moving objects is more massive when they collide than they were separately, before they collided. All of that mumbo jumbo about leftover energy can be interpreted as a mass increase: the energy of motion has become additional energy of mass. Said, another way:

Mass + Energy is the thing

Mass, by itself, is not conserved. Mass energy plus energy of motion is always conserved.

4.3.1. Particle Physics: the sum is worth more than the parts¶

One of the discoveries in particle physics that I was involved in was the discovery of the most massive elementary particle we know of: the “top quark.” We’ll learn all about that later, but what’s relevant here is that we collided protons with the antiparticles of protons. Antiparticles are identical to their particle counterpart, except they have the opposite electrical charge. So they have the same mass.

Remember that I said I’d sometimes refer to the mass of a proton as “1” in dimensionless units? This will be more of an issue in later lessons, but some nomenclature:

Note

Antiparticles will be written with a “bar” over the top.

So an electron is \(e\) and an anti electron would be \(\bar e\). (It’s so useful in medicine and other areas of life that it has a name: the positron.)

A proton is \(p\) and so an antiproton is \(\bar{p}\).

A top quark is \(t\) and …you get it, right? The anti-top quark is \(\bar t\).

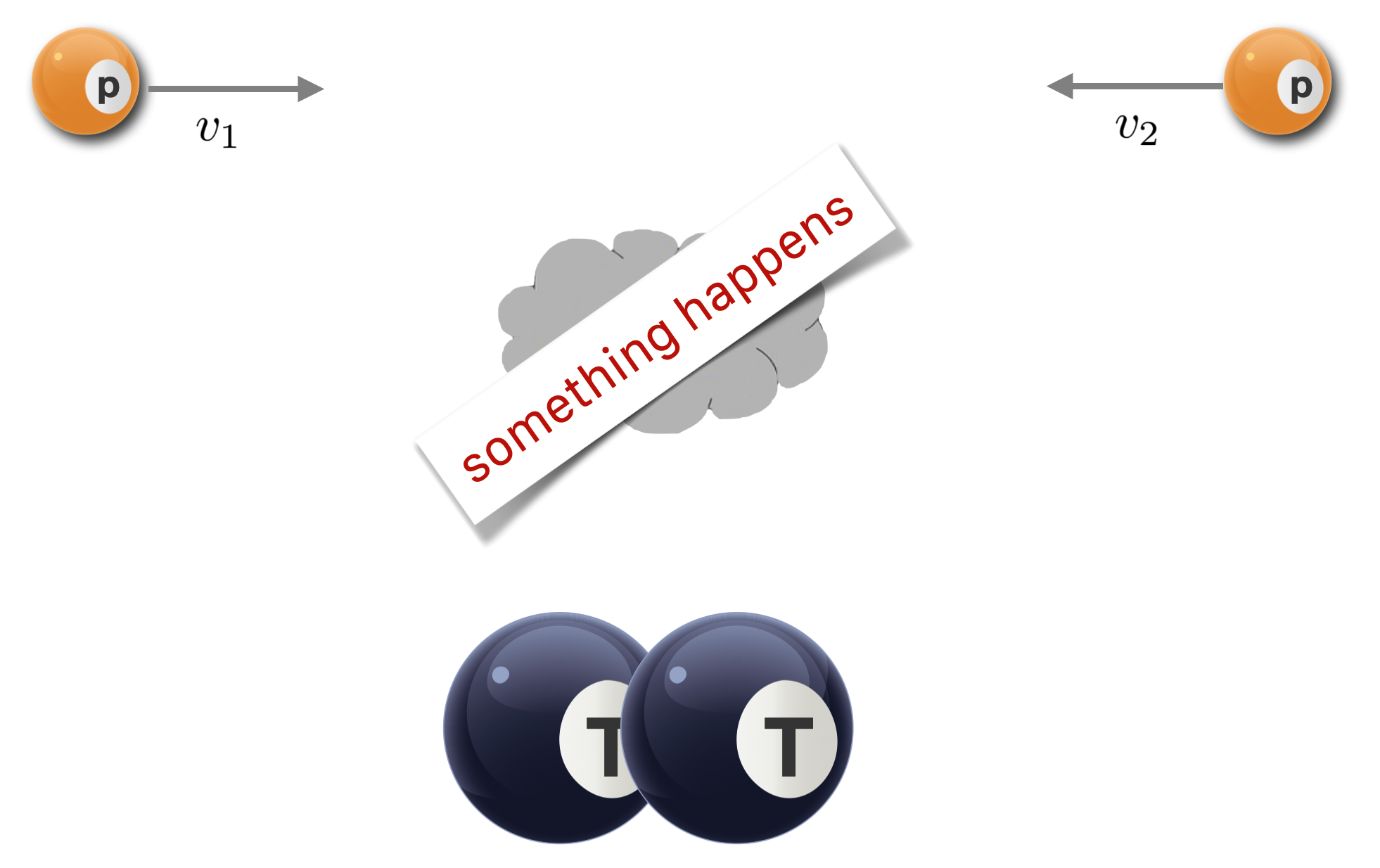

Here’s where relativity is useful as a tool. Our top quark discovery reaction was:

Here’s a cartoon, where the “before” is at the top, then the physics of annihilation and creation is some very short time later (middle) and the two top quarks are the result, at the bottom.

Fig. 4.17 MARGINCAP¶

Here’s a kind of surprising fact:

So if you add up the masses in the initial state of the colliding proton-antiproton set you get \(m(\text{before})=2\) and the masses of the resulting top-quark pair, \(m(\text{after}) = 2 \times 173 = 346!\)

That’s why we must accelerate the protons and antiprotons to very, very high energies – so that the energy of motion in the beams can be turned into energy of mass in the final products. Sweet.

Here’s a colorful model for the collision of two objects into two objects:

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

Fig. 4.18 MARGINCAP¶

Look at each term carefully. Because we’re going to create new matter.

Let’s make a cartoon particle accelerator, in the spirit of the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva. Two protons are accelerated around a huge, evacuated pipe (steered by magnets and accelerated in electric fields as we’ve discussed). In this play-accelerator, they are brought together in one place where they collide.

At the top, we see them coming toward one another

At the bottom they’ve disappeared and created two, new…things, \(t\). The things are much more massive than the original protons.

Wait. Disappeared? Like Beam me up, Scotty?

Glad you asked: Not quite and as maybe you’ve heard me say before, stay tuned. We will talk about that when we get to quantum mechanics where the explanation is both beautiful and weird.

Fig. 4.19 MARGINCAP¶

Here is the reaction formula for a proton from the Left colliding with a proton from the Right to make two “things,” \(t(1)\) and \(t(2)\):

Feynman Diagram for the process:

Fig. 4.20 MARGINCAP¶

Wait. What happens in the gray blob?

Glad you asked: That’s a quantum mechanics model that we’ll get to. Stay tuned. Sorry.

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

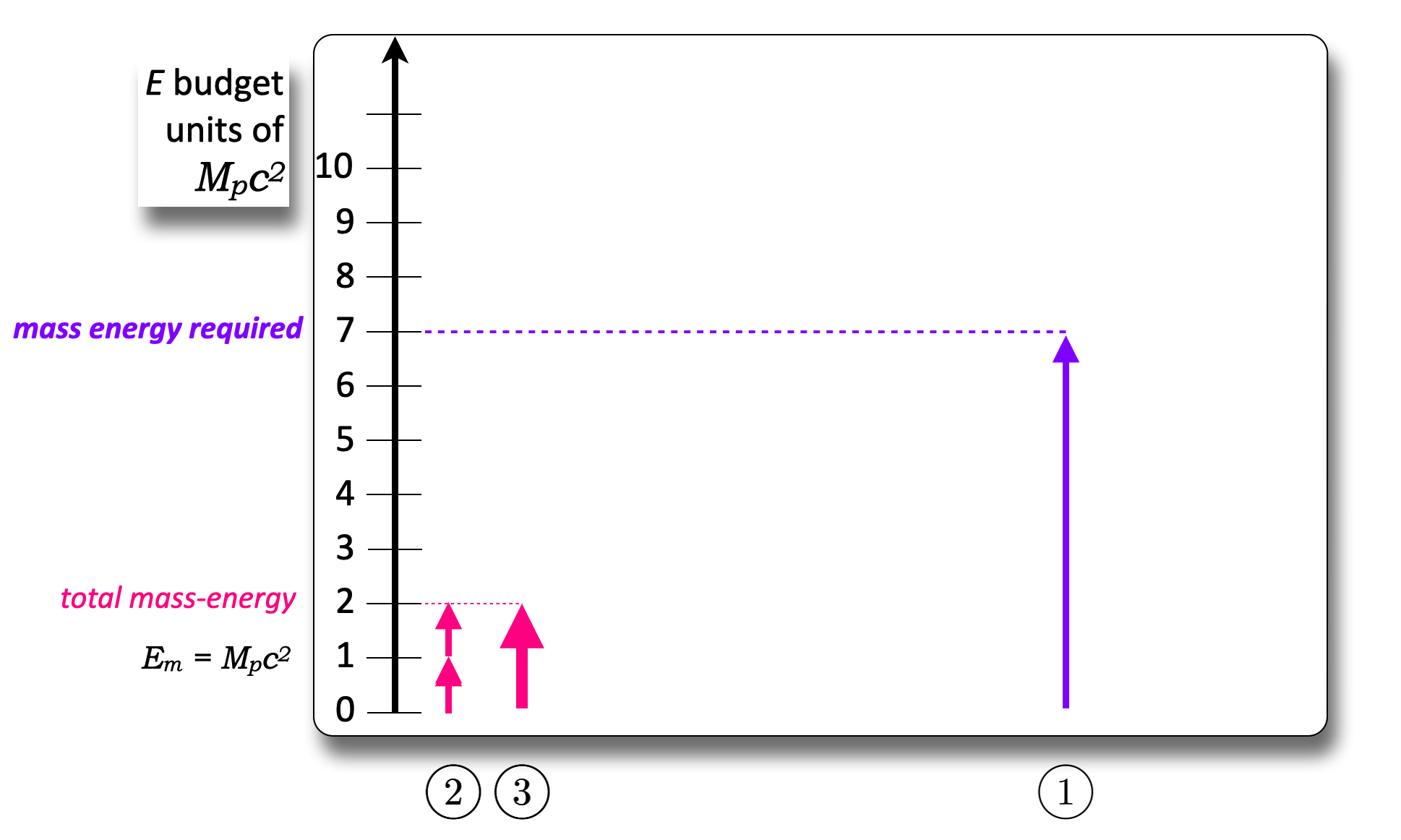

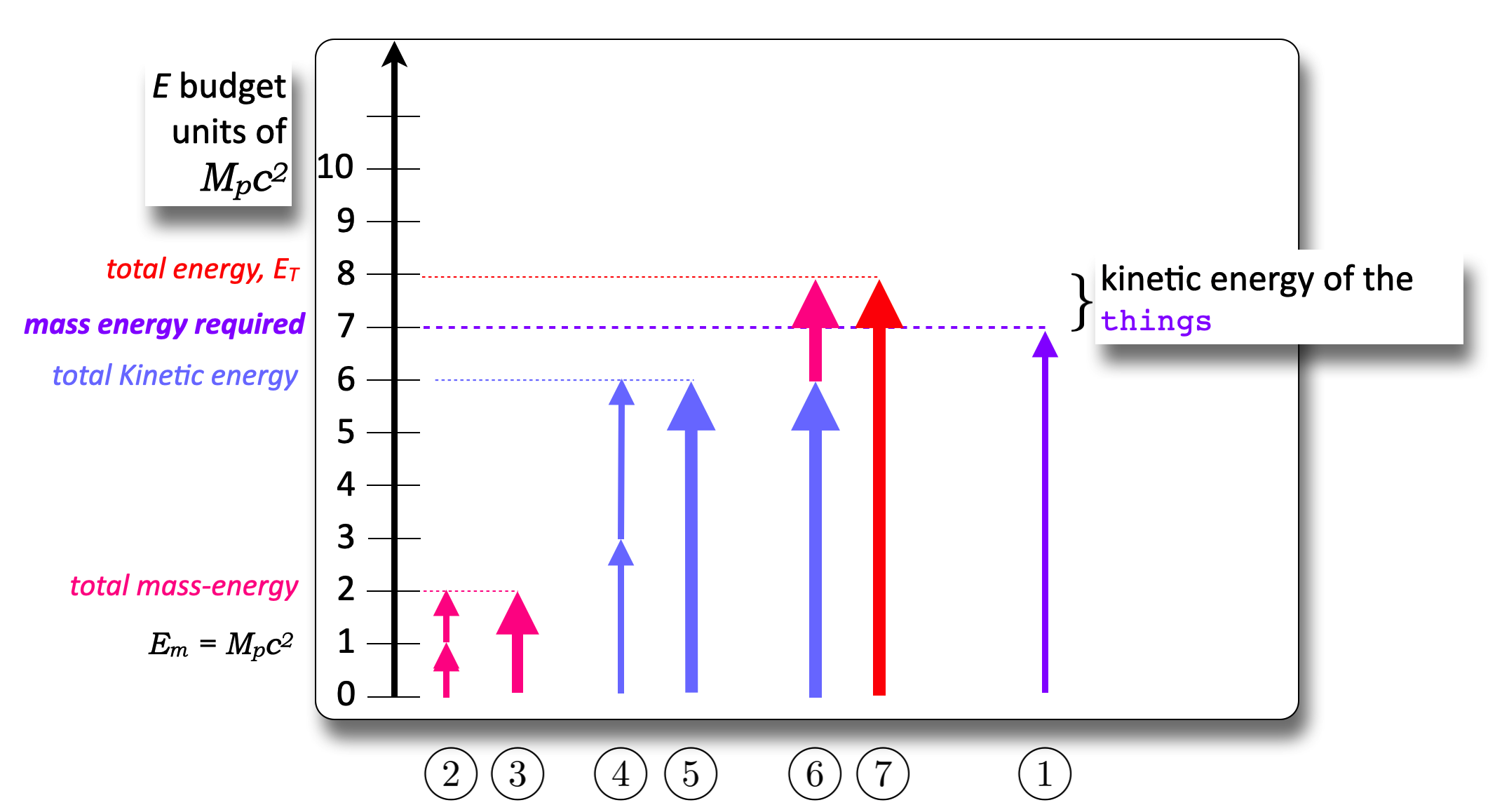

Here are the ground rules for this game. Although energies would typically be Joules, or electron volts, we’ll just use fake energy units scaled to the mass-energy of a proton.

The mass of a “thing” is big:

Nature only produces pairs of “things” so the minimum mass-energy required to create two things is:

Finally, the protons are moving – fast. So there’s kinetic energy in their motions of three times the mass-energy of a proton:

From our energy conservation equation we can keep track of the before energies and the after energies:

The question is whether there is enough total energy in the beam protons to be able to make two “things” in the collision.

You’ll need a worksheet that you’ll find on-line in the course pack. It looks like this:

Fig. 4.21 MARGINCAP¶

Let’s add it up:

Let’s imagine a chart on a whiteboard. Here is the total mass-energy of the two beam protons:

Fig. 4.22 MARGINCAP¶

The vertical axis will tally energies of each of the objects scaled in units of our fake units of \(m_pc^2\):

The mass-energies of each proton.

This totals to 2.

The total mass-energy required in order to make two things is \(2 \times 3.5 = 7\).

Now let’s add in the kinetic energies:

Fig. 4.23 MARGINCAP¶

Each beam proton had \(K=3\) .

So the total of the beams’ energies of motion is 6.

Putting it all together:

Fig. 4.24 MARGINCAP¶

The kinetic energies plus the total mass energies of the protons

totals to 8.

As you can see, we needed \(E_T = 7\) but the collision provided a total energy of \(8\), more than required in order to just make two things.

Wait. So what happens to the extra energies?

Glad you asked: The things are not just hanging around after they’re produced. There is energy left over after they are created as real particles…and so they’re moving. They acquire some kinetic energy.

The two, shiny new “things” have kinetic energies of their own of \(K_\text{things} = 1\).

What we just did is solve the energy conservation equations:

A lot of relativity is pretty elementary math.

That. In a nutshell is much of the goal of particle physics: make new things by using relativity (and quantum mechanics) out of very fast old things.

Please answer question 4 📺

4.3.2. Some Chemistry: as viewed by a physicist¶

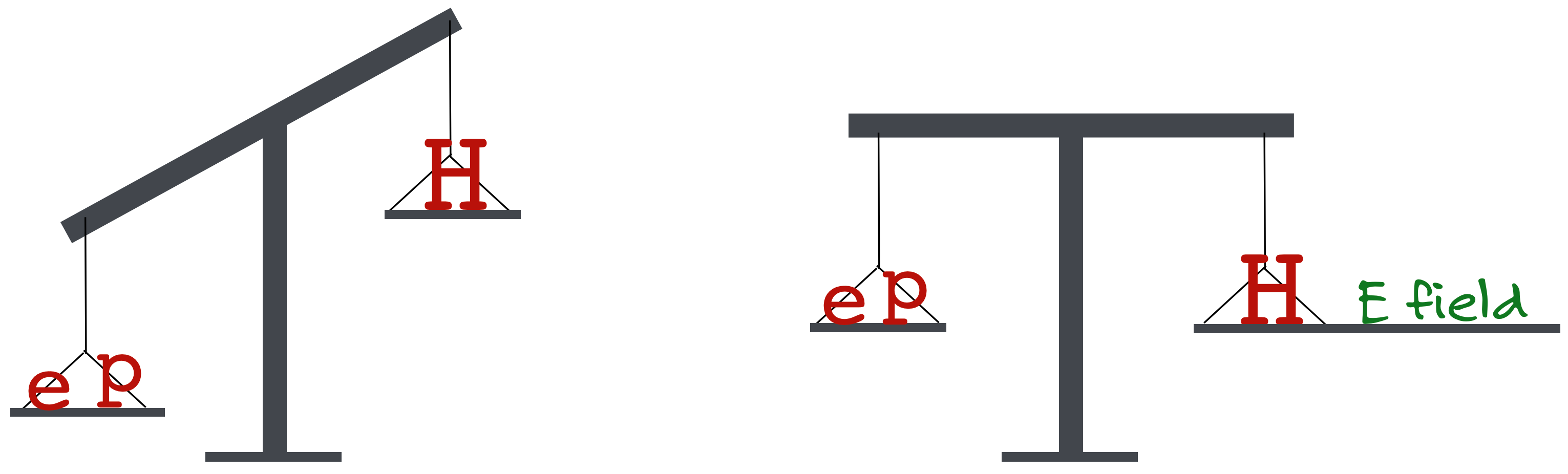

Remember the hydrogen atom is one proton and one electron and that electron and proton are bound together by the electrostatic attraction due to their opposite electronic charges. Maybe you remember from chemistry that in order to liberate the electron – to “ionize” hydrogen, you must supply a particular minimum energy of 13.6 electron volts or \(2.18 \times 10^{-18}\) J.

You would have learned that the electron is “bound” to the proton with a potential energy that’s negative. The energy diagram would look like this in a chemistry class on the left and a physics class on the right:

Fig. 4.25 MARGINCAP¶

Let’s look at each item here by the circled numbers in the diagram.

The left side, the chemist picture:

1. The hydrogen energy level diagram is a succession of energy levels from the lowest – which is the most stable – to the highest, which is complete ionization….liberation of the electron.

2. For chemists, the zero of energy is when the electron has been liberated…that’s zero chemical energy.

3. When the electron is bound, it has a negative electrostatic potential energy of \(-13.6\) electron volts.

4. Give an electron a hit of \(+13.6\) eV (like from a photon), and it will be promoted away from the proton and is no longer bound: it’s a separate proton and a separate electron.

The right side, the physicist picture:

5. For the physicist the zero of energy is where there is no motion and there is no mass.

6. For hydrogen, the energy is all in the mass of the hydrogen atom.

7. For a real proton and a real electron, which are not bound together into an atom, the energy is just \(m_pc^2 + m_ec^2\). Notice that this value goes to the zero value of the chemist picture: an independent and isolated proton and electron.

Why does the electron stay bound to the proton in hydrogen in the relativistic picture? Because the mass of a hydrogen atom is less than the mass of an electron and a proton. So it cannot just rattle apart into those two particles since

So how to reconcile this? Remember that what’s not in the picture is the electric field.

We know from Maxwell that the electric field has energy.

We know from Einstein that energy and mass are equivalent.

So the “missing mass” in the hydrogen atom is resident in the energy of the electric field.

It’s all accounted for!

Fig. 4.26 MARGINCAP¶

Since, after all, energy is mass and mass is energy. This same idea is what happens inside of nuclei and that “mass deficit” can be liberated, either in a controlled way – nuclear power – or an explosive way – nuclear weapons.

Everything you’ve learned about energy can be cast in this light. Potential energy can be done away with:

Raise a mass above the ground? You increase its mass. That’s what we’ve called potential energy.

Heat up your eggs in the morning? They become more massive. The jiggling of the molecules in the eggs which we would call heat, can be interpreted as an overall increase in the eggs’ mass.

Energy suddenly becomes a simple idea! And, it’s always conserved…as long as mass-energy is included in the accounting.

Please answer question 5 📺

4.4. Isn’t Anything Constant??¶

Wait. So, isn’t everything relative?

Glad you asked: So it would seem. But it’s not quite like that and what’s really important is actually what is always constant. That’s where Einstein’s frustrated university mathematics instructor comes in.

As we learned from the introduction to this lesson, in 1908 Minkowski put Special Relativity on a sophisticated mathematical foundation. His formulation first frustrated Einstein who grumbled:

“[about] superfluous learnedness…” “Since the mathematicians have grabbed hold of the theory of relativity, I myself no longer understand it.”

But he soon realized the importance of “invariance” in physics and made use of that notion many times later.

Invariance

Invariance: something that is unchanged under some “transformation.”

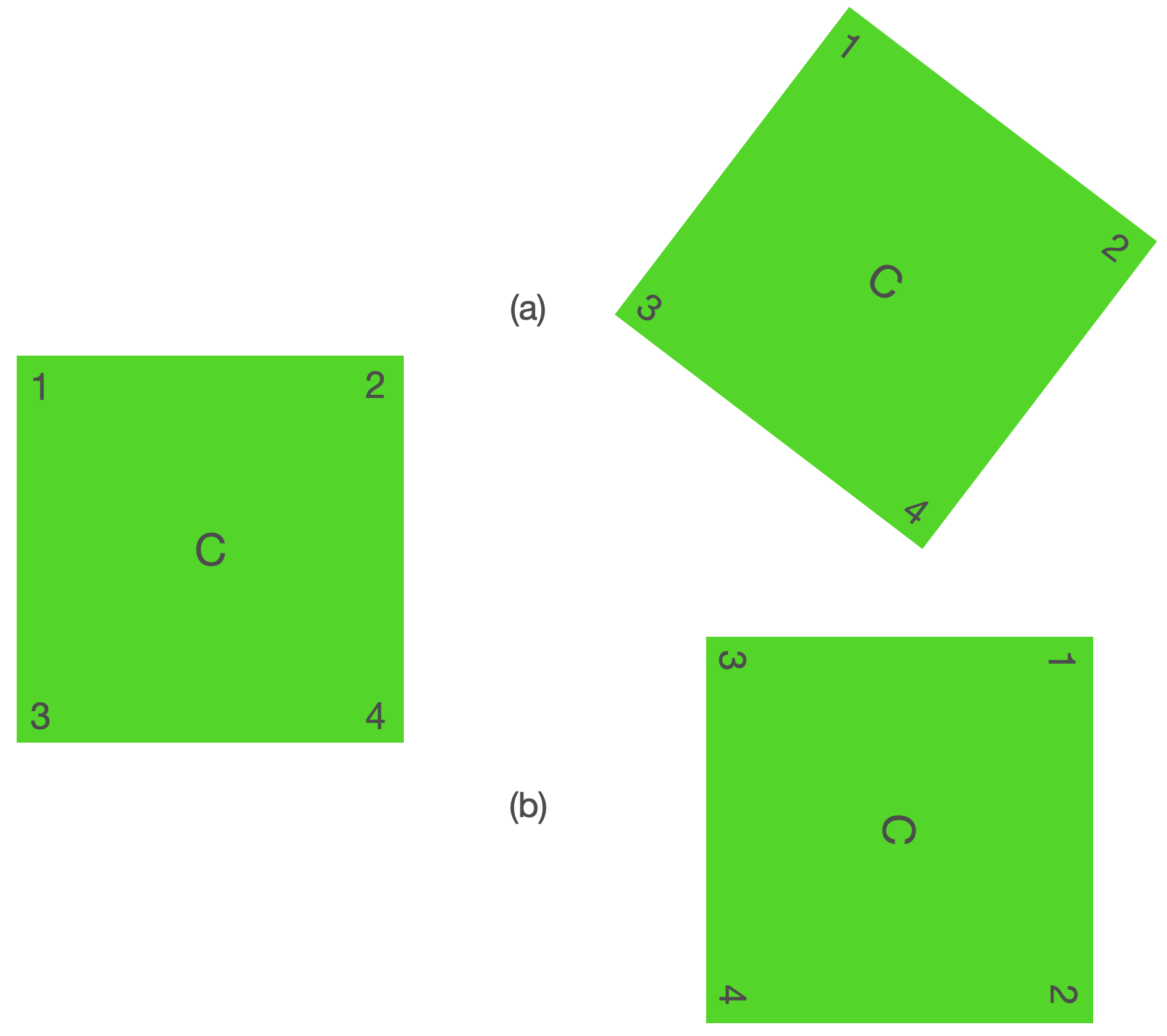

I want to hint at some pretty mathematics from 50,000 feet. The idea of a mathematical “transformation” is a very important idea and in fact governs modern physics in a deep way.

Suppose we have a square in front of us. A perfect, mathematical square. Let’s pretend that we can mark the corners to keep track of them as we play. But the numbers don’t do anything but guide the eye. Each corner is identical to the others.

A transformation is here a rotation of the square around its center, C.

Fig. 4.27 MARGINCAP¶

What kinds of transformations would leave the square “invariant”? That is, if I ask you to close your eyes and then I rotate the square around its center and ask you to open them, would you be able to tell whether it changed or whether it stayed the same?

If I did a rotation like (a) above, you’d say that the square was not the same. So we could conclude that a square is NOT invariant against a transformation of +45º about its center.

If I did a rotation like (b) above, you would not be able to tell that anything changed. Indeed, a square is invariant with respect to a transformation of 90º about its center. And 180º and 270º, 0º, and 360º. These are the only transformations that leave a square invariant.

Minkowski was an expert in the branch of mathematics called then, “Invariant Theory” and now “Group Theory” and he understood well that the manipulative description that I just gave could be constructed as math equations – functions – for which a transformation on the function leaves it unchanged in its form.

For example, remember that the equation for a circle is:

Suppose (in the same sense as you closing your eyes before the square manipulation) we transformed the \(x\) values that define the edge of a circle this way:

Every \(x\) becomes a minus \(a\). What is the new equation?

This has the same FORM as the original. It doesn’t matter what the variables are called. In this Group Theory game, what matters is the FORM of an equation. So a circle is invariant with respect to the transformation of its variables into their negatives.

4.4.1. Let’s Go to the Ballpark¶

Have you ever thought about how major league baseball stadiums are laid out? No?

Seriously. Baseball parks?

Glad you asked: Stay with me. Invariance is afoot.

The MLB Rule Book says that…ahem:

Rule 1.04: “THE PLAYING FIELD: It is desirable that the line from home base through the pitchers plate to second base shall run East Northeast.”

Since baseball is not played in the morning, this orientation would minimize the likelihood that a batter would be staring into the sun. The advent of night baseball, indoor stadiums, and prevailing winds in various locations led to modern era baseball diamonds to be oriented in all sorts of different directions.

Here are two:

Fig. 4.28 MARGINCAP¶

The left-hand figure is a picture of what the Rule Book demands and the elderly Wrigley Field in Chicago was constructed precisely that way, while the modern CoAmerica Park went its own way to accommodate its city streets. (Again, batters will face east, but southeast. Still no sun.)

Is everything relative in baseball? Well, no! The distance from home plate to the pitcher’s rubber is 60 feet, 6 inches in every ball park.1

Notice in the figure above that there are two \(x-y\) axes drawn on top of each diamond, \(x_C-y_C\) for the Cubs and \(x_T-y_T\) for the Tigers. Notice too that a circle has been drawn centered on home plate – the origin of the two coordinate systems – in each of the parks. That circle has a radius of 60’ 6”.

Let’s write the formula that models that circle. There are two of them:

Clearly, these formulae look the same, and in the sprit of the above discussion it doesn’t matter what the names of the variables are, the form of the equations are identical. We would say that the length is invariant with respect to the choice of coordinate system since the \(L_P\) for each ballpark is the same 60’ 6”.

In a flat space of the sort you might have learned the geometry of in high school, for any number of coordinate systems, we could write:

where now the different coordinate systems are called 1, 2, or 3 and not Cubs, Tigers, Yankees…

This is very much like a well-worn example: Suppose a town hires two contractors to work on the creation of a set of streets in town. The first contractor uses magnetic north for his surveying jobs and the second contractor uses polar north for hers. The streets that they proposed to construct would be identical, street to street, corner to corner, house to house.

Let’s look at such a circle as described by three different coordinate systems.

That circle that’s traced out when the axes are aligned is called the Invariant Curve. You can see that an invariant length from your high school geometry class is represented by a circle.

What’s critical here is those plus signs. Any time that you find a length to be invariant and modeled by:

you know that you’re working in the high school geometry – called Euclidean Geometry – after the Greek mathematician who wrote the book that everyone learned from for 1500 years. Euclidean Geometry is the geometry that governs points, lines, and planes on a flat surface. This will become critical in Einstein’s future in more than one surprising way and we’ll draw the contrast more than once as we move through his work.

Here’s where Einstein’s frustrated math professor comes in. Let’s have a baby.

4.4.2. Minkowski’s Geometry¶

What we’ve seen so far is that relativity is going to mix space and time.

We call the relativistic combination of space and time: Spacetime.

A natural question is what’s the “length” in space and time: Spacetime? What’s the invariant curve for relativity?

Note

What would that mean? It would be a way to describe an invariant interval as viewed from all possible reference frames. Following around the invariant curve would take you from Home to Away to another Away and another.

Let’s try the Euclidean Invariant curve for the “length” of space and time.

Note

Space and time are similarly dealt with so far, but they have different dimensions, right? Space might be measured in meters and time might be measured in seconds. Not the same. But we have a way around that. By convention we’ll use a “space” dimension for time by always multiplying t by c.

A proposal: We might guess that the “length” of a space and time interval (we use “\(\Delta s\)” to represent a spacetime interval) that the space and time coordinates would lead to a circle in Spacetime just like our “regular” space of ballparks and surveyors. For our “1” and “2” relatively moving coordinate systems, we might try

Seems reasonable, but let’s go to the hospital and think about what a Spacetime geometry of this sort might look like.

On the left of the figure below is then our proposal. (Notice that we can easily distinguish the future, with times greater than zero, from the past, where time would be negative given the choice of the origin.)

On the right is a “situation” for us to think about with that assumption.

Fig. 4.29 MARGINCAP¶

So we’re in the delivery room at a hospital. At the \(x=0\) point the newly born baby is first…well, born…and then some time later at that same space point, she cries, at the point labeled \(A\). Normal biological stuff. It’s a cause for celebration and little while later in time everyone in the family cries.

Suppose we’re driving by the hospital and somehow (don’t ask how) we observe that same blessed event. Now as time progresses, so does our distance from the origin, so we all agree that the baby is born at the origin but we see the first cry at point \(B\), since we’ve moved in our frame. That’s maybe not too hard to imagine.

Now we drive by in a different direction – a different frame, that Special Relativity should be able to describe. We again see the baby born at the origin but uh-oh. Before the birth, the baby cries. If the circle is the space and time invariant curve then the rules of relativity should work for all points on the curve – this proposed circle.

But that’s not how births happen! The first crying event for every newborn is after, not ever before, the birth. We have to conclude that the Euclidean circle is not the invariant curve for Special Relativity. In the abstract, this is not just a silly example, it implies a violation of cause and effect. Where an effect seems to happen before its cause. Not good.

While the maternity ward was not on Hermann Minkowski’s mind, he did figure out the correct kind of geometry to describe events in Special Relativity. It was a new geometry that he invented and today we call the space in which that geometry functions, Minkowski Space.

4.5. Spacetime¶

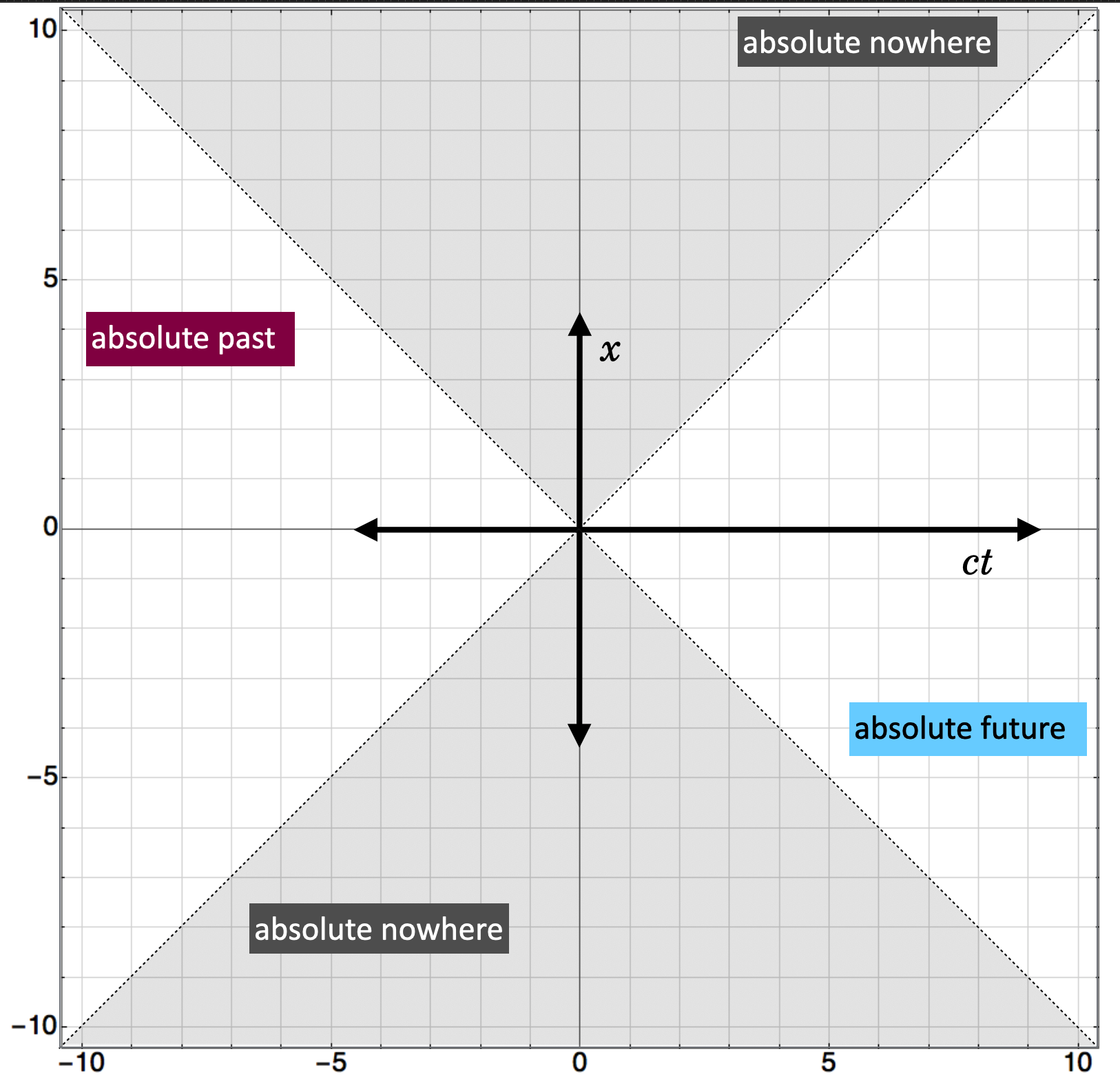

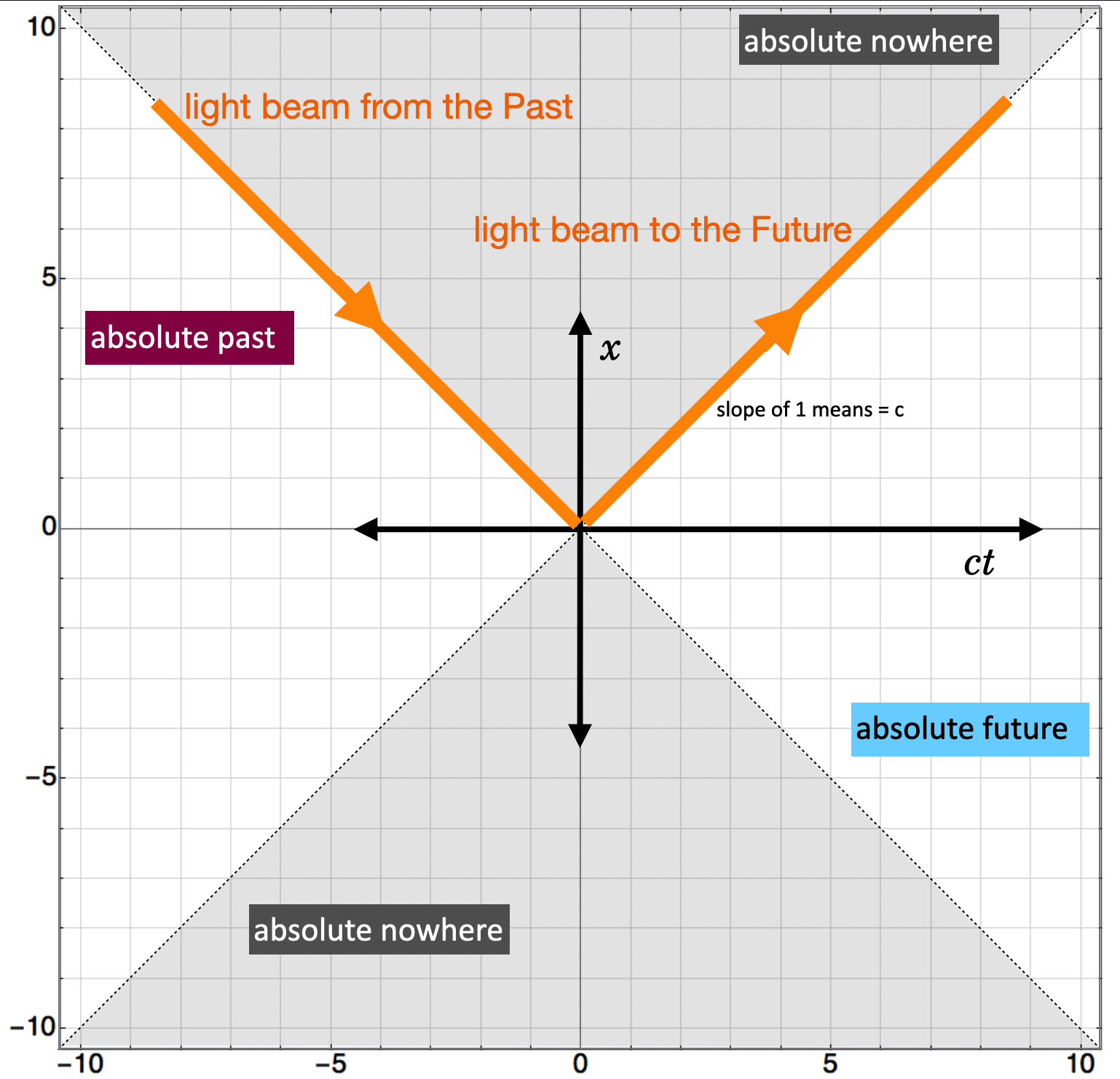

Let’s get familiar with Spacetime. My ability to draw in 4 dimensions is nil. So we’ll write only time horizontally (remember \(ct\)) and \(x\) vertically, proudly representing all three space dimensions. Stand proud, \(x\)!

4.5.1. Digging Into Spacetime¶

Look at this figure with time on the horizontal axis (remember, \(c \times t\) and one dimension of space on the vertical.

Fig. 4.30 MARGINCAP¶

You’ve seen this many times. The origin of this plot is where we are right now. All frames would agree on this point as we’ve done with trains in our earlier lessons.

The 45º angles are important since the slope would be

So a trajectory in spacetime for an object that moves at the speed of light is 1. This is a light-like, or “light curve.” These diagonals create a multidimensional volume that looks like a cone, the Light Cone.

Fig. 4.31 MARGINCAP¶

So, the diagonals delineate four different regions of spacetime:

In the future, where \(t>0\):

inside of the light curve are objects that leave from us at less than the speed of light. You know, normal stuff. We’d call that region the Absolute Future.

outside of the light curve are objects that leave from us at greater than the speed of light. You know, stuff of science fiction! We’d call that region the Absolute Nowhere.

In the past, where \(t<0\):

inside of the light curve are objects that move at less than the speed of light. You know, normal stuff. We’d call that region the Absolute Past.

outside of the light curve are objects that move at greater than the speed of light. You know, stuff of science fiction! We’d call that region the Absolute Nowhere.

The trajectories of all objects follow their “Worldline” which is of course inside of the light cone.

Fig. 4.32 MARGINCAP¶

Notice one other thing about this:

Note

There are regions of spacetime at any point which are unreachable from the past – could not have influenced us – and unreachable in the future – we can not communicate with them. The universe has expanded fast enough by now that there are places in our universe with which we have no contact.

It’s inside this new space of spacetime that we now need to address the lingering question of what is the Invariant Curve for spacetime? That’s where Einstein’s frustrated university math professor enters the scene.

4.5.2. Minkowski Space¶

We know that the circle will not work in Spacetime. Otherwise, we’d be seeing babies everywhere before they arrive.

What Minkowski rigorously found was that a Spacetime length is not represented by

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

but rather by:

This is not the equation of a circle! See those negative signs? Let’s make it just one dimension:

The \(H\) reminds us that we’re talking about a spacetime length in some \(A\) frame moving frame as viewed by us, \(H\), maybe lots of us moving relative to one another and that \(A\) frame. All inertial observers would agree on the length of a spacetime interval according to this formula, just like we would all agree on the length from home plate to the pitcher’s rubber in flat “regular” space.

Note

This is the equation of a hyperbola. Spacetime is hyperbolic in shape.

Let’s plot this on our spacetime diagram.

Fig. 4.33 MARGINCAP¶

On the left in the figure is a situation for all observers of some event that happened at a time \(0.5\) units of time in the Home frame. You can see that in the blowup around the origin where for no change in \(x\) (after all, it’s in the “stationary” frame). Every point on that red curve are spacetime points that can be reached for a “proper time” of 0.5. That’s the time in the rest frame of the object that’s moving relative to all of the others. You can see that it’s 0.5 as it’s the shortest distance between the origin and the curve and where there is no change in the space dimension – a horizontal line at \(ct=0.5\) .

Now let our object move a little further (live a little longer in the Away frame), to \(ct=1\).

Fig. 4.34 MARGINCAP¶

Here’s the counter-intuitive thing about an hyperbola. Let’s go back to the airport. The moving sidewalk has a constant speed, which we could (and did) plot on our graph as a positively sloping line. We can draw arrows on the diagram from our common point of when time starts to some time later. For the weary traveler, that line appears to be longer than it is for the couch people, but in that formula of the relativistic interval, \(\Delta s^2\) are the same for both. We’ll work that out in an example.

So, there are three important quantities that are NOT relative in Special Relativity!

The speed of light, \(c\).

The interval, \(\Delta s^2 = (c\Delta t)^2 - (\Delta x)^2\).

The “invariant mass,” \((\Delta mc^2)^2 = E_T^2 - (pc)^2\).

Even this silly equation expresses a common feature with the last two above: $\( (\text{Bob})^2 = (\text{Mary})^2 - (\text{Sam})^2 \nonumber \)$ It doesn’t matter what the variables are called. That the form of the equations are the same expresses a deep mathematical feature of that new kind of geometry. That’s what Minkowski found.

4.6. The Aftermath¶

It might be worth reviewing a little of Einstein’s personal timeline since 1905.

1906: Promoted to Technical Expert Second Class.

1906: He published six papers.

1907: He published 10 papers.

1907: Establishes the Principle of Equivalence (stay tuned)

1908: Turned down as a high school teacher and completes his habilitation thesis in order to qualify for entry university teaching.

1908 (Finally) appointed as a lecturer at the University of Bern

1908: Minkowski’s geometrical interpretation of Spacetime.

1909: Resigns from the Patent Office(!)

1909: Appointed Associate Professor of Theoretical Physics at the University of Zurich

During the years leading up to 1905 – five years – he worked alone, except for fruitful discussions with his Olympia Academy friends. He complains about not having access to any university library, so he cannot read scientific papers.

4.6.1. The Real Physics Olympia: Berlin¶

Einstein’s devoted sister wrote that Einstein had hoped for some recognition: “…he was bitterly disappointed…icy silence followed the publications.”

In the western world at the turn of the 20th century, there was no institution that remotely compared with the University of Berlin. And there was no higher authority in physics, especially in Theoretical Physics, than the Professor of Theoretical Physics, Max Planck. I’ll have lots to say about Planck when we get to Quantum Theory, but suffice it to say, if there was ever an 800 pound gorilla in Theoretical Physics in 1905, it was Planck. That turns out to be important.

Planck was on the editorial board of the primary physics journal in the world, Annalen der Physik and was in charge of theoretical submissions. So all of Einstein’s 1905 papers required his approval. This would be hard to do today.

Einstein didn’t even qualify to be classified as prominent as “unknown”…he could not have been lower on any professional rung. He had no PhD. He had no scientific job. He suffered the opposite of good recommendations.

And yet, Max Planck took his papers seriously and by 1906, was giving seminars on Relativity and published a correct derivation of the relativistic momentum relation. He and Albert began corresponding. His “bitter disappointment” turned into enthusiasm. Planck publicly defended a subtle point of criticism of Relativity and Einstein joined in, along side of his senior correspondent. Planck replied in January of 1907 with:

“As long as the proponents of the principle of relativity constitute such a modest little band as is now the case…it is doubly important that they agree among themselves.”

Planck suggested that he would like to travel to Bern to meet Einstein in person. Planck could not make the trip and so he sent his assistant, Max Laue. It was only upon preparing to go to Bern that Laue (and Planck) discovered that Einstein was not at the University of Bern…nor at any university at all. When he got to the third floor of the Post and Telegraph building, “The young man who came to meet me made so unexpected impression on my that I did not believe he could possibly be the father of the relativity theory…so I let him pass.” Einstein wandered back through the reception area and they made contact.

They spent hours together and eventually Laue published eight papers himself on relativity and they became fast friends.

4.6.2. Nothing Is Simple¶

The academic ladder in Europe at the time, and still in many places today, requires not only an original PhD degree, but a second PhD called the “habilitation.” Einstein didn’t want to bother, but failed at the high school job application that he made he succumbed to convention, qualifying for the degree at Bern. Soon a more prominent position opened at the University of Zurich where Alfred Kleiner persuaded the university to create a position in Theoretical Physics, albeit at the associate professor level. Two applied: Einstein, whom Kleiner knew and liked, and Friedrich Adler a friend of Einstein’s from their college days.

The job was to go to Adler, but he actually went to Kleiner to complain that it should instead go to Einstein. Einstein’s reputation for having zero people skills made that a difficult decision for Kleiner but he went to Bern to hear Einstein teach a class. It was terrible. Einstein knew it and regrettably word of it got out around Europe: Einstein was “a long way from being a teacher.” Einstein was furious and wrote to Kleiner complaining that vicious rumors were being spread about him. About Adler:

Note

Adler was an enigma, and a murderer. His father was a powerful official in the Austrian Social Democratic party, to which Friedrich was a zealot participant. In 1911 he gave up science to become a journalist and partisan. He was against the Austria-Hungary war policy and on October 21st in 1916 young Adler calmly entered a hotel restaurant and shot and killed the Austrian minister-president Count Karl von Stürgkh, three times with a pistol. He made no effort to flee and admited his guilt. He was sentenced to death, but that was commuted by Emporer Charles to 1-18 years in prison. He was released at the end of WWI and lived to be 80 years old in 1960.

Kleiner acquiesced and advised Einstein to try one more time, this time in Zurich. Einstein did it. “Contrary to my habit, I lectured well on that occasion.” In spite of faculty reservations about Einstein’s “Jewishness” he was offered the job, which paid less than his Patent Office position. “So, now I too am an official member of the guild of whores.”

Finally, by 1908 - eight years after he completed college and three years after he changed the world in multiple ways, Einstein was a fully credentialed university professor.

4.7. Is Relativity The Case?¶

Of course, just being a novel idea is not sufficient for the acceptance of a theory. It has to pass experimental tests and here too, nothing was simple for Einstein.

Remember that Lorentz’s theory of the ether was in many ways predictably identical to Relativity. That included a Lorentzian view of mass which also would predictably increase with speed (relative to the ether). In 1901 there were competing theories based on ideas of electromagnetism that differed from Maxwell’s and Lorentz’. Walter Kaufmann, whom we’ll learn more of later, took on the challenge to measure whether the mass of an electron varied with velocity. More particularly, he measured the so-called “charge to mass” ratio, which can be determined by accelerating a charged particle through an appropriately designed sequence of electric and magnetic fields. (We’ll learn about this when we discuss the discovery of the electron by the Englishman, J.J. Thomson.)

Kaufmann was a very patient and skilled experimenter, but he got it wrong. His measurements were analyzed by him to disfavor the Lorentz prediction (and of course consequently, the 1905 Einstein prediction). Kaufmann did experiments in 1901, 1902, 1903, and 1905 and concluded:

“The prevalent results decidedly speak against the correctness of Lorentz’s assumption as well as Einstein’s. If on account of that one considers this basic assumption refuted, then one would be forced to consider it a failure to attempt to base the entire field of physics, including electrodynamics and optics, upon the principle of relative movement. “

In that same year, Planck took the highest velocity nine data points from Kaufmann’s paper and reanalyzed them and found multiple mistakes. That led to many more measurements in various labs and by 1914 it was clear: the Einstein (Lorentz) interpretation of the change of mass with speed was confirmed and the alternatives were ruled out.

We’ve already talked about some of the classic tests of Special Relativity and today, it’s a tool and not “just” a theory. Its combination with Quantum Mechanics has led to the most precise predictions and confirmations of those predictions in history.

And yet, Einstein’s Nobel Prize ignored relativity.

The mass measurements weren’t the end of problems for Special Relativity.

4.7.1. “Jewish Science”¶

Anti-semitism was in the fabric of European life

“As remarkable as Einstein’s papers are…it still seems to me that something almost unhealthy lies in this unconstruable and impossible to visualize dogma. An Englishman would hardly have given us this theory… the abstract conceptual character of the Semite expresses itself.” Arnold Sommerfeld, Nobel Laureate

This was the beginning of the attack on “Jewish Science” by the National Socialists Party in Germany..early 1930s

“Materialistic natural science had eclipsed the “spiritual sciences,” giving rise to the “arrogant delusion“ that humankind can achieve the “mastery of nature…That influence has been strengthened by the all-corrupting foreign spirit permeating physics and mathematics…” Philipp Lenard, Nobel Laureate

“The scientist does not exist only for himself or even for his science. Rather, in his work he must serve the nation first and foremost. For these reasons, the leading scientific positions in the National Socialist state are to be occupied not by elements alien to the Volk but only by nationally conscious German men.” Johannes Stark, Nobel Laureate

“His theory is not the keystone of a development, but a declaration of total war, waged with the purpose of destroying what lies at the basis of this development, namely, the world view of German man … This theory could have blossomed and flourished nowhere else but in the soil of Marxism, whose scientific expression it is, in a manner analogous to that of cubism in the plastic arts and the unmelodies and unharmonic atonality in the music of the last several years [“degenerate science”!]. Thus, in its consequences the theory of relativity appears to be less a scientific than a political problem.” Bruno Thüring

“The simple question that precedes every scientific enterprise is: who is it who wants to know something, who is it who wants to orient himself in the world around him? It follows necessarily that there can only be the science of a particular type of humanity and of a particular age. There is very likely a Nordic science, and a National Socialist science, which are bound to be opposed to the Liberal–Jewish science, which, indeed, is no longer fulfilling its function anywhere, but is in the process of nullifying itself.” Adolf Hitler

Eventually, it became unsafe for Einstein to remain in Germany and he emigrated to the United States in 1932.

[to do - the Opera experiment]

Let’s go paint a house in Bern.

4.8. What To Remember from Lesson 18¶

4.8.1. A New Kind of Energy¶

Mass is a kind of energy. In an object’s own rest frame, the value of that energy is:

As viewed by an observer in a co-moving inertial frame, that energy would appear to be:

This can be interpreted as observing that a moving object appears to have more mass than its value measured within its own rest frame:

where “relativistic mass” is sometimes used to represent that quantity. In our terms, this might also be written:

With some algebra, we can write the total energy of an object in another way:

where \(K\) is the relativistic kinetic energy.

- 1

There are so many strikeouts in the current game (2021) that there’s talk of taking some advantage away from the pitchers by lengthen the distance to the mound.