Lesson 4 Mathematics, The M Word

A tiny bit of mathematics. Really.

4.1 Contents

4.2 Goals of this lesson:

- I’d like you to Understand:

- Simple one-variable algebra.

- Exponential notation.

- Scientific notation.

- Unit conversion.

- Graphical vector addition and subtraction.

- I’d like you to Appreciate:

- The approximation of complicated functions in an expansion.

- I’d like you to become Familiar With:

- Aspects of Descartes’ life.

- The importance of Descartes’ merging of algebra and geometry.

4.3 A Little Bit of Descartes

The 16th and 17th centuries hosted a proliferation of pre-scientific and scientific “Fathers of” figures: Galileo Galilei, the Father of Physics; Nicholas Copernicus and Johannes Kepler, arguably the Fathers of Astrophysics; and Tycho Brahe, the Father of Astronomy. That leaves out some lesser-known, but influential dads-of, like Roger Bacon, Frances Bacon (no relation), and Walter Gilbert, all of whom share paternity as Fathers of Experimentation. But the Granddaddy…um…Father of them all was René Descartes (1596-1650), often referred to as the Father of Western Philosophy and a Father of Mathematics, if not a favorite Uncle of Physics. If you’ve ever plotted a point in a coordinate system, you’ve paid homage to Descartes.

Frankly, if you’ve ever plotted a function, you’ve paid homage to Descartes. If you’ve ever looked at a rainbow? Yes. Him again. If you ever felt that the mind and the body are perhaps two different things, then you’re paying homage to Descartes and if you were taught to be skeptical of authority and to work things out for yourself? Descartes. But above all—for us—René Descartes was the Father of analytic geometry.

He was born in 1596 in a little French village called, Descartes—what are the odds? (Okay. That came later.) By this time Galileo was a professor in Padua inventing physics and Caravaggio was in Rome inventing the Baroque. Across the Channel Shakespeare was in London inventing theater and Elizabeth had cracked the Royal Glass Ceiling and was reinventing moderate political rule. This was a time of discovery when intellectuals began to think for themselves. This is the beginning of the end of the suffocating domination of Aristotle.

René was sent to a prominent Jesuit school at the age of 10 and a decade later emerged with his mandated law degree. Apart from his success in school, his most remarkable learned skill was his lifelong manner of studying: often ill, he was allowed to spend his mornings in bed, a habit he retained until the last year of his life. There’s a story there.

His school required physical fitness and in spite of his health, he became a proficient swordsman and soldier—wearing a sword throughout his life as befitting a “gentleman.” For a while he was essentially a soldier of fortune, alternating between raucous partying in Paris with friends and combat assignments (a Catholic, fighting with the Dutch Protestants) in various of the innumerable Thirty Years War armies.

Somewhere in that period Descartes became serious and decided that he had important things to say. He wrote a handful of unpublished tracts and became well-known through a steady correspondence with European intellectuals.

By 1628 he began to suspect that his ideas were not going to sit well in Catholic France ( confirmed for him when Galileo was censured in 1633) and so he moved to Holland where he lived for more than 20 years. He’d been playing with mathematics during his playboy-soldier period and little did he know surprisingly, he found he was a mathematical genius, solving problems that others couldn’t. He enrolled himself as a “mature student” in Leiden and devoted himself to mathematics. By 1637, he changed the landscape forever.

4.3.1 Descartes’ Algebra-fication of Geometry…

…or geometri-fication of algebra! Descartes brought geometry and algebra together for the first time.

The fledgling field of algebra (“al-jabr” from the Arabic, “reunion of broken parts” ) was slowly creeping into European circles…along with the decimal point (Galileo had neither) and solutions of some kinds of polynomial equations were appearing. The notation was clumsy.

So geometry held on as king of mathematics. What Descartes did was link the solutions of geometry problems—which would have been done with rule-obsessive construction of proofs—to solutions using symbols. He did this work in a small book called Le Géométrie (The Geometry), which he published in 1637, the same year he published his philosophical blockbuster, Discourse on Method. In it he instituted a number of conventions which we use today. For example, he reserved the letters of the beginning of the alphabet \(a, b, c,...\) for things that are constants or which represent fixed lines. An important strategic approach was to assume that the solution of a mathematical problem may be unknown, but can still be found and he reserved the last letters of the alphabet \(x, y, z...\) to stand for unknown quantities—variables. He further introduced the compact notation of exponents to describe how many times a constant or a variable is multiplied by itself, \(x^2\) for example.

The early translators of al-jabr to, um, algebra considered equations in two unknown variables like \(y = \text{some combination of } x\)’s to be unsolvable. But Descartes linked one variable, say \(y\) to the other as points on a curve that related them through an algebraic equation—what came to be called a function. He called one of those variable’s domain the abscissa and the other, the ordinate. The use of perpendicular axes, which we call \(x\) and \(y\), stems from Descartes’ inspiration which is why they’re called Cartesian Coordinates.

Mathematicians picked up on these ideas and extended them into the directions that we know and love. One of those was John Wallis (1616-1703), the most important Cambridge influence on Isaac Newton.

4.3.2 Descartes’ Philosophy: New Knowledge Just By Thinking?

The rigor of the mathematical deductive method stayed with him and became a new kind of philosophy that he called “analytic.” Famously, he convinced himself that he had deduced a method to truth: whatever cannot be logically doubted, is true. The clue was that when you mentally and relentlessly doubted something and can’t go any further, then that idea has become “clear and distinct.” True, for him. Using this method, he decided that this demonstrated that his mind exists and that he, a thinker, is thinking these things and therefore he exists.

So by using a mathematical-like deductive path, he believed that he had made an important discovery—a proof of his existence. This is his famous bumper sticker conclusion called forever “the cogito”: Cogito ergo sum, I think, therefore, I am. But that’s not what he wrote in Meditations on First Philosophy. This is closer: “So after considering everything very thoroughly, I must finally conclude that this proposition, I am, I exist, is necessarily true whenever it is put forward by me or conceived in my mind.” Big bumper. But you know how legends go.

This is the philosophy of Rationalism which he is the king—the discovery of knowledge through pure thought. Rationalism has been in direct philosophical conflict with the philosophy of Empiricism— and as you’ll see, often physics is caught in the middle. Rationalism is in the spirit of Plato, but unlike Descartes, the Greek gave up on the sensible world as simply a bad copy of the Real World, which is one of Ideas…”out there” somewhere. By contrast, by asserting that mind and matter were both existent realms, Descartes decided that one could understand the universe by blending thinking (mind) with observing (body).

We physicists take some inspiration through Descartes’ approach. Theoretical physicists are often motivated to gain knowledge through thought, always deploying mathematics—so maybe thought and paper. Experimental physicists sometimes claim that knowledge can only be obtained through observation (and in modern form, experiment). Most of us are of the latter devotion, but can sometimes be amazed at how often smart physicists by just thinking can lead to new knowledge of the world. We’ll meet many of these folks. It’s sometimes a strange way to make a living.

After a public dispute—even in the Netherlands—Descartes began to imagine that his time among the Dutch was coming to a close. Queen Christina of Sweden, was an admirer and an intellectual and she invited Descartes to Stockholm to work in her court and to instruct her. After multiple refusals, not being a monarch to whom “no” is an easy answer, she sent a ship to Amsterdam to pick him up. He eventually accepted the position which was the beginning of his end.

The Queen required his presence at 4 AM for lessons. This, from the fellow who had spent every morning of his life in bed until noon! He caught a serious respiratory infection and died on February 11th, 1650 at the age of only 53.

We moderns owe an enormous debt to this soldier-philosopher-mathematician. Both for what he said that was useful and for what he said that was nonsense, but which stimulated a productive reaction. I think that there is a direct line from every QS&BB lesson that goes right back to René Descartes.

4.4 The M Word

I promise that the math of QS&BB will not be hard and we’ll get through it together. In this lesson I’ll develop most of the tools that we’ll return to repeatedly: simple algebra, some familiar geometry, exponents, and powers of ten.

Wait. Why use mathematics in a book for non-science people? I’m not a math person!

Glad you asked. Two reasons. First, there is a direct connection between a mathematical description of a phenomenon and nature itself. As I said, we don’t know why that’s the case and the argument about whether mathematics is “discovered” or “invented” is endless.

Second, it’s much more economical than using words.

Finally, it’s a little deductive engine for many of our purposes. You can “discover” things by manipulating the symbols…things that will further explain the physics.

I guess I lied. That’s three reasons.

Oh. There’s no such thing as a “math person” at the level we’ll be using math!

I had a decision to make in designing a set of lessons about physics for non-experts: use no mathematics or use some. Let me show you what I decided, and why. But first, here’s my guide to the use of mathematics in QS&BB:

We’ll use mathematics as a language to be “actively read” and a part of the narrative. But you’ll not have to derive things on your own from scratch.

Wait. What’s “active reading”?

Glad you asked. It means reading with your pencil moving. When you see this suggestive symbol:

🖋 📓 \(\leftarrow\) (see them?)

the page will turn a color and you start “close-reading” the colored material by writing in your notebook…filling blanks, making notations, even copying what your eyes see — yes, by all means copy what you are reading! (I do when I learn something new.) Then when it’s time to stand down, the page will go back to white and you can go back to “just” reading,

Wait. I don’t have a notebook.

Glad you asked. Please get one for the full QS&BB experience ;) I’ll wait. (tapping foot)

4.4.1 A Tiny Bit Of Algebra

Our algebraic experience here will involve some simple solutions to simple equations. I’ll need the occasional square root and the occasional exponent, but no trigonometry or solving simultaneous equations and certainly no calculus. I’ll refer to vectors, but you’ll not need to do even two-dimensional vector-component calculations. What’s not to like?

If I’d chosen to avoid all mathematics in QS&BB then I think something important would be missing. To learn about QS&BB ideas would be like learning how to paint but ignoring a particular color…where “red” should be, you’d insert a tiny note saying that “red should be here.” <I’m convinced that absorbing a simple equation, which stands for something in the world, is a cognitively different experience from reading its symbols in a sentence.

4.4.2 An example of the power in symbols

Later we’ll learn the most fantastic model of motion that Isaac Newton invented—his Universal law of Gravitation. It explained the moon’s orbit around the earth, the planets’ motions around the sun, and still guides spacecraft through the solar system today. I could just tell you about it, or I could write it as an equation…a model.

Let’s compare two extreme approaches: I’ll write out the content of the Gravitation rule in an English paragraph and in its algebraic form. Then we’ll compare.

Unlike in Fight Club, let’s talk about this battle:

In this corner: Newton’s Gravitational law as a paragraph

“The force of attraction experienced by two masses on one another is directly proportional to the product of those two masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distances that separate their centers. The constant of proportionality is called the Gravitational Constant which is \(0.0000000000667408\; \text{m}^3 \text{kg}^{-1}\text{s}^{-2}.\)”

There. A perfectly good, if not moving, literary description of Newton’s rule. Lots of words, but it’s complete and it’s accurate. But it’s also inefficient and worse, it’s… lifeless.

Let’s contrast this with the mathematical opponent:

And in this corner: Newton’s law of Gravitation in symbols:

\[F = G \frac{mM}{R^2}\]

F stands for the force of gravitation, \(m\) and \(M\) stand for two masses, \(R\) is the distance between them, and \(G\) is a number…that tiny number in the paragraph.

That’s it.

I claim that in addition to the obvious efficiency of the symbolic, compact notation…there’s **insight* buried inside of an equation that’s not in an English sentence. For example, here’s a perfectly good interesting question about gravitation:

🖋📓

A question! How might you guess at the approximate force of attraction that the moon feels from the Sun compared with the force of attraction that the moon feels from the earth?

Glad you asked. The paragraph-representation is not helpful. But the symbol-equation-representation is very easily manipulated to answer a question of it. Twist it around and it’s ready to tell you something new.

Good job!

🖋📓

Question! So do it: What is the approximate force of attraction that the moon feels from the Sun compared with the force of attraction that the moon feels from the earth?

Glad you asked. We could answer the question by forming the ratio of the two situations. Here’s just the answer, postponing the actual solution to the lesson on gravity:

\[\begin{align*}

r(\text{SunEarth}) & =\frac{F_{Sm}}{F_{Em}} = \frac{G \frac{mM_S}{R_{Sm}^2}}{G \frac{mM_E}{R_{Em}^2}} \\

& = \frac{M_S}{M_E}\frac{R_{Em}^2}{R_{Sm}^2} \\

\end{align*}\]

Good job!

It looks like distance matters a lot since it’s involvement is squared. Putting in the values for masses and distances, you’d find that the moon feels the Sun almost twice as much as it feels the earth. That information was buried inside of the symbolic representation…but not in the paragraph.

The symbolic approach is agile. It gives us a path to the physics. It’s alive! The paragraph just sat there. Watching.

There’s physical insight to be gained by looking at a function that describes—or maybe is?—nature.

4.5 Functions, the QS&BB Way

The language of physics is mathematics, uttered Galileo a long time ago (although he said that the language of the universe is mathematics). Well, he was right. And we have no idea why that seems to reliably be the case!

“The miracle of the appropriateness of the language of mathematics for the formulation of the laws of physics is a wonderful gift which we neither understand nor deserve. We should be grateful for it and hope that it will remain valid in future research…”

This is from the last paragraph of a notorious and actually, delightful essay written by the physicist Eugene Wigner in 1960. The title is The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences where he tries to dig into the strange relationship between the physical world and mathematics. It’s famous: ask Mr Google to find “Unreasonable Effectiveness” and you’ll get 150,000 references to Wigner’s essay.

I hope you see my point: The English paragraph and the succinct mathematical function do the same job, on the surface. However, that “miracle” of the connection between the universe and mathematics is really only apparent when we make full use of the manipulative features of symbols in an equation where we can uncover new things.

4.5.1 Functions rule

One of the remarkable consequences of the mathematization of physics that began with Descartes is that we’ve come to expect that our descriptions of the universe will be in the language of mathematical functions. Do you remember what a function is? The fancy definition of a function can be pretty involved, but you do know about function machines and I’ll remind you how.

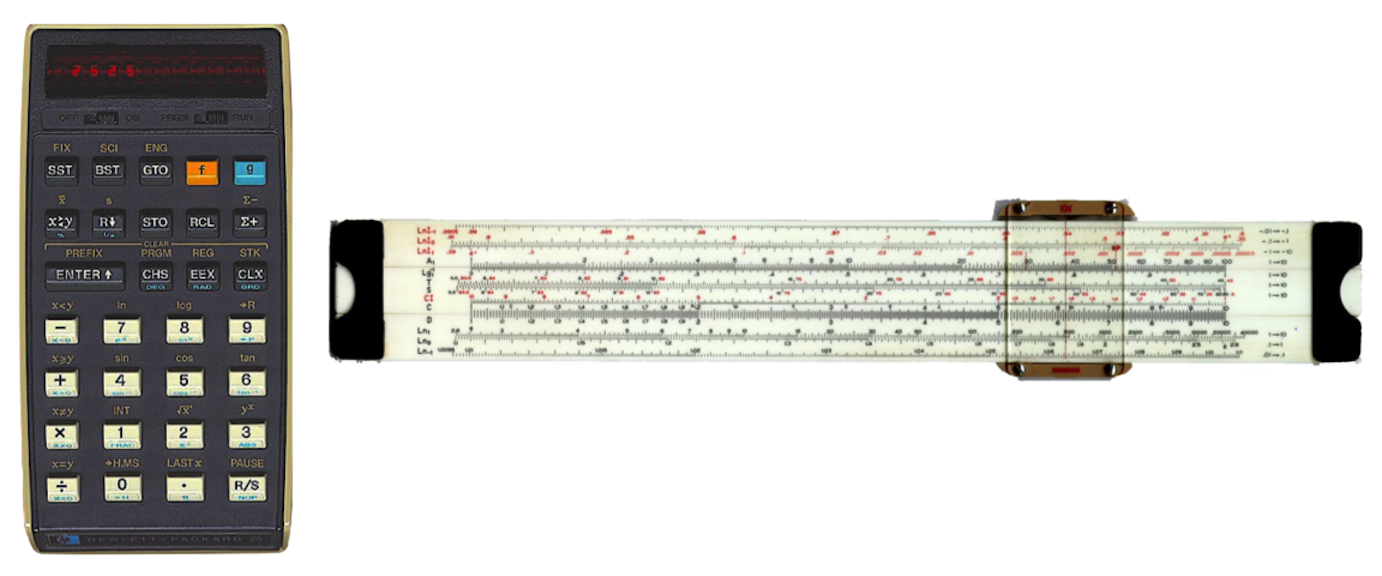

When I was a senior in college, finishing my electrical engineering degree, our department had a visitor from the Hewlett Packard Company. It was either Bill Hewlett or Dave Packard, I can’t remember which. But he promised to do away with the slide rule that we all carried around with us everywhere and showed us a brand new product: a portable scientific calculator, that they called the electronic slide rule. This was 1972 and he showed us the first HP calculator, the HP-35. Needless to say, I couldn’t afford it—it cost $400 then— but later in graduate school I bought my first scientific calculator, the HP-25, pictured here, along with that slide rule that I carried for four years.

Figure 4.2: Left: the venerable HP-25 programable (!) scientific calculator. Right: a slide rule used for all calculations until the early 1970’s. It was not programmable (although it was wireless)

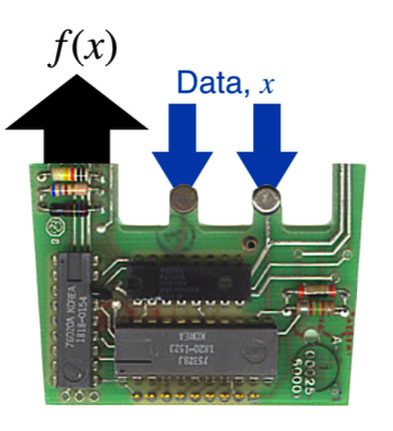

Today I’ve got more processing power in my watch then I had in that calculator. But I’ll bet you’ve got something like it…calculators are nothing but electronic function machines. In fact, this is the arithmetic circuit inside of that original calculator:

Figure 4.3: The AMI 1820-1523 Arithmetic, Control Timing processor: the heart of a function machine. Adapted for my silly purposes: the tabs at the blue arrows are actually connecting the processor to the keyboard. That’s how data got in.

The calculator guts shows what a function does: if you enter data through the keypad — a value of \(x\) — and hit the appropriate button, the display shows the value of the function. So if the function was the formula \(f(x) = x^2\) and if I keyed in “4” and pushed the \(x^2\) button, the display would read “16,” the value of \(f(4)\) for that particular function. Notice that it doesn’t give you more than one result, and that’s a requirement of a function: one result.

That’s all a function is: a little mathematical machine that reports a single result for one or more inputs according to some rule. For us, functions can be represented by a formula, an algorithm, a table, or a graph. In all cases, it’s one or more variables \(x\) or \(x \; \& \; y...\) or \(x \; \& y \; \& z...\) in, a rule about what happens to them, and one numerical result out.

Nature seems to live by functions and since we’re all about nature, we’ll need to use functions. Our way.

4.5.2 Turn the crank, QS&BB style

We’ll accomplish a lot without much mathematical effort, I promise you. In fact, we’ll find that the raw mathematics of modern physics is simple. What’s hard is the conceptual visualization.

Some physics models are simple and we can easily deal with them in their “raw” mathematical form…and some are really quite complicated. With a little help from Mr Descartes or some whimsy, we’ll manage. So three ways we’ll work with mathematical models.

4.5.2.1 We’ll write them and manipulate them for real.

Can you solve the equation: \(y = ax\) for \(x\)? You’ll be surprised just how often an equation of that form will describe sophisticated aspects of the world.

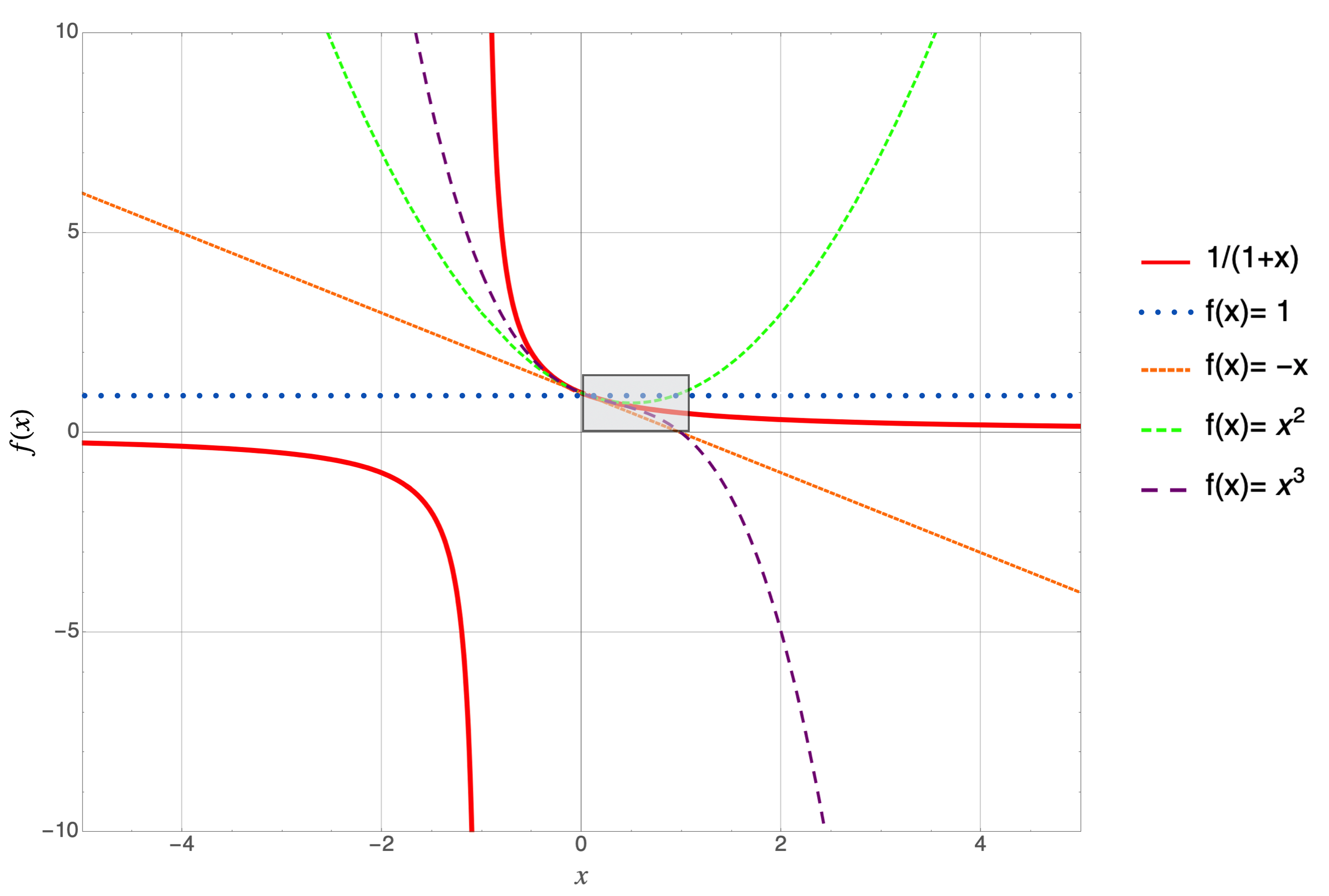

4.5.2.2 We’ll Plot them.

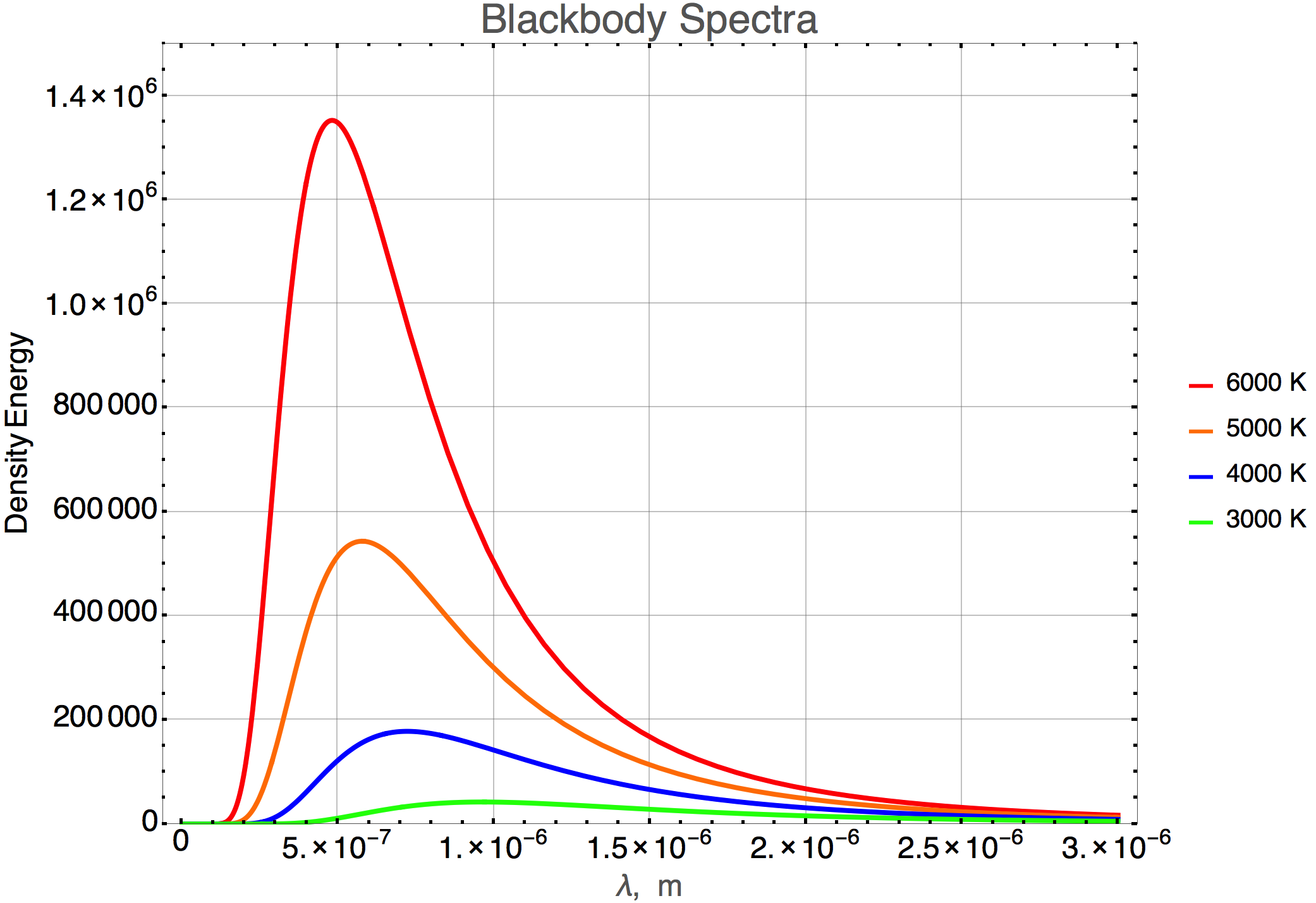

If I want to deal with a model that uses sophisticated mathematics quantitatively, instead of working with the formulas…I’ll just show you the functions are plotted. Here’s an example, a really important model in physics which we’ll refer to a number of times. The function is messy and I don’t want to lose track of the physics by getting you bogged down in evaluating the it.

Figure 4.4: This is the intensity of a heated object as a function of wavelength of the radiation for different temperatures (noted in units of Kelvin).

You’d have no problem telling me the relative intensities of say the blue and the red curves—4000 degrees and 6000 degrees—at a wavelength of 1 micron, \(1 \times 10^{-6}\) m. Right? Much easier than plugging into Mr Planck’s formula.

4.5.3 We’ll represent with a circuit. A silly circuit.

If we’re talking about a really complicated model, perhaps one with many formulas and lots of high-brow calculus or even worse, I’ll show you a cartoon and ask you to take my word for it.

Remember in your past you might have heard someone use the phrase, “turn the crank…” that’s sort of old language for plugging in some numbers and doing some laborious calculation…. We’ll not do that. I’ll just show you this figure, properly filled out for the circumstance at hand:

![The evaluation of a candidate physical model (which is a function or a set of functions) requires some inputs [the equation(s), maybe some data, some core beliefs (other trusted models),and some plan...a strategy]. The result is a prediction which would almost always be a prediction for some measurable quantity.](images/beginning/crank.png)

Figure 4.5: The evaluation of a candidate physical model (which is a function or a set of functions) requires some inputs [the equation(s), maybe some data, some core beliefs (other trusted models),and some plan…a strategy]. The result is a prediction which would almost always be a prediction for some measurable quantity.

What will be important here is that we all agree on the assumptions in the model, the tools used to solve it, and any data that might be a part of the calculation of interest. You’d have no problem imagining a computer solving something or running some (game?) simulation and that’s all this fake circuit represents. Something in, some instructions, and something out. We move on.

4.6 A Gentle Review 1: Skills You’ll Frequently Need

There are three levels of math refresher in this lesson:

This section: skills that you’ll use a lot during the semester. Please familiarize yourselves with these topics and read seriously until you see the stop sign: 🛑

Skills that you’ll use only a few times. Skim this. Know that it’s there, but don’t dig in now unless you want to.

Some boutique skills that might be necessary only once. Just know that they’re there.

You might find it useful to brush off some previous skills that we’ll need to make progress. I have in mind simple algebra, exponents, powers of 10, and some simple geometry formulas.

4.6.1 Some Algebra Practice

I’ll show you some examples of the level of algebra we’ll need, but let’s first pause and salute the most important thing about algebra:

The Fairness Doctrine of Algebra: If you do something to one side of an equation, you must do the same thing to the other side.

Words to live by. Armed with this, here we go. You’ll be surprised how simple this will be.

Wait. It’s been a long time since I took algebra. I don’t like where this is heading.

Glad you asked. Can you sing or play an instrument? You can read music and glean meaning and insight from playing music…but I’ll bet you’ve not composed music. I want to use mathematics in that spirit. I’ll ask you to play along — read algebra — but almost never will I assess your progress in QS&BB by asking you to compose — derive — mathematical arguments.

Here’s a representative list of the kinds of mathematical thinking I’ll ask you to be able to read:

- \(y=mx + b\) presents four parameters — symbols that stand for something. For this example, I’ll define \(b\) and \(m\) as constants. A numbers… like “3.” The \(y\) and \(x\) are variables and have a particular one-to-one relationship that comes from the context: the value of \(y\) depends on the value of \(x\). \(y\) is the dependent variable and \(x\) is the independent variable. We would say that “\(y\) is a function of \(x\).”

🖋 📓

A question! In symbols, can you solve this equation for \(x\) as a function of \(y\)?

Glad you asked. Yes.

Bad job! That’s not what I meant and you know it.

Glad you asked. Be specific. Here’s how I’d do that, and I’ll insert every step even though you might do some of them in your head:

\[\begin{align*} \text{work out the strategy to isolate $x$:} \;\;\; y &= mx+b \\ \text{get rid of $b$ on the right:} \;\;\; y - b &= mx +b - b \\ y-b &=mx \\ \text{get rid of $m$ on the right:} \;\;\; \frac{y-b}{m} &= \frac{mx}{m} \\ \frac{y-b}{m} &= x \\ \text{just rearrange it in order ot admire the result:} \;\;\; x &= \frac{y-b}{m} \end{align*}\] Good job! “Function” is a $100 word but really just an algorithm…a machine: put in an \(x\) and you get out a \(y\). That’s all a function does.

Now, let’s solve that equation.

🖋 📓

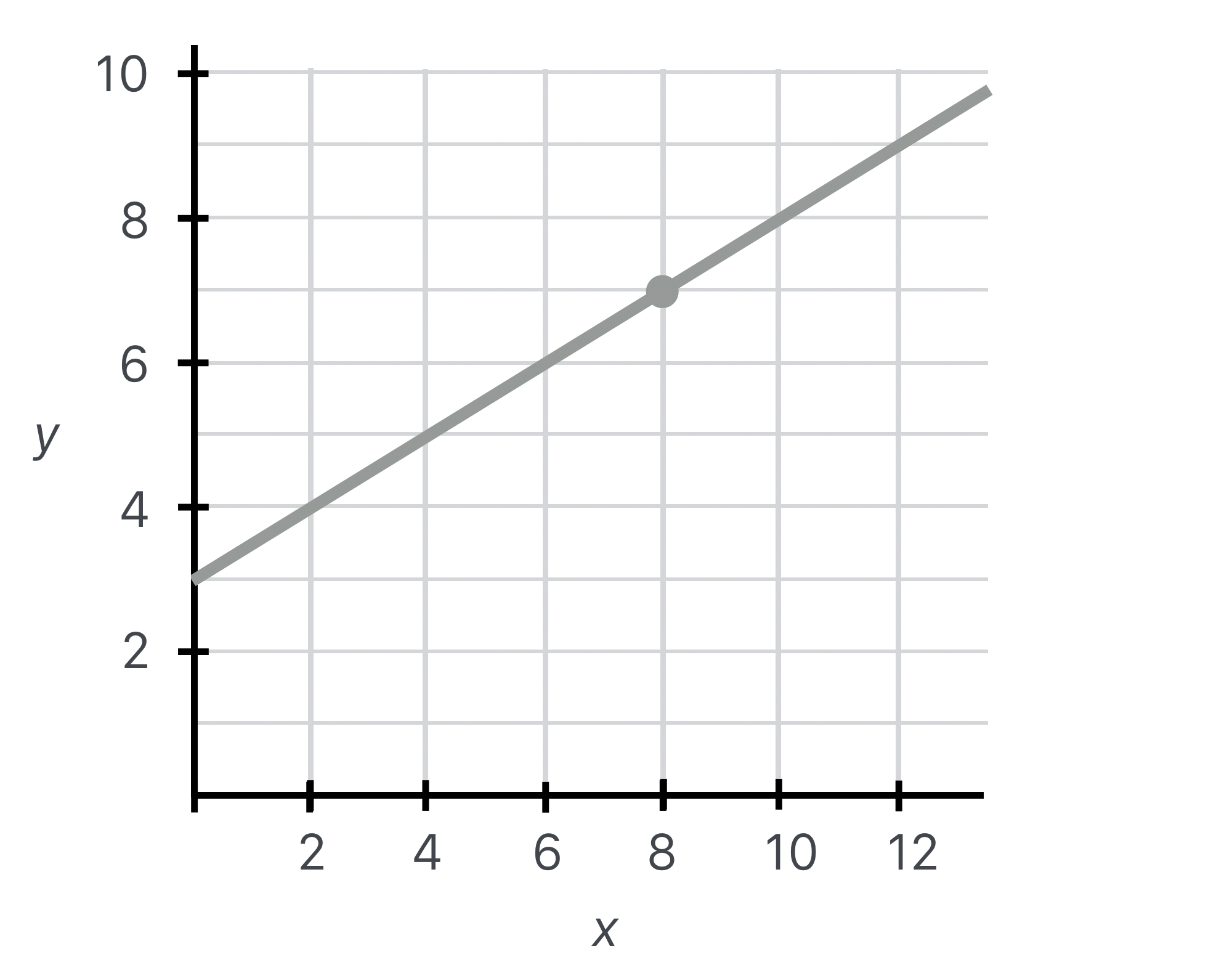

A question! If \(b=3\) and \(m=0.5\), what is the value of \(y\) if \(x=8\)?

Glad you asked. I’d put in the values and do the calculation:

\[\begin{align*}

y &= mx + b \;\;\; \text{ always set the stage by starting at the beginning} \\

y &= (0.5)(8)+3 = 4+3 = 7

\end{align*}\]

Good job!

Now. Maybe you recognize this particular equation…remember from somewhere in your life the sentence: “y equals mx plus b”? The equation for a straight line.

All equations can be graphs —- that’s from the brilliance of primarily Rene Descartes as you’ve read above. But let’s plot it and see how to solve it graphically:

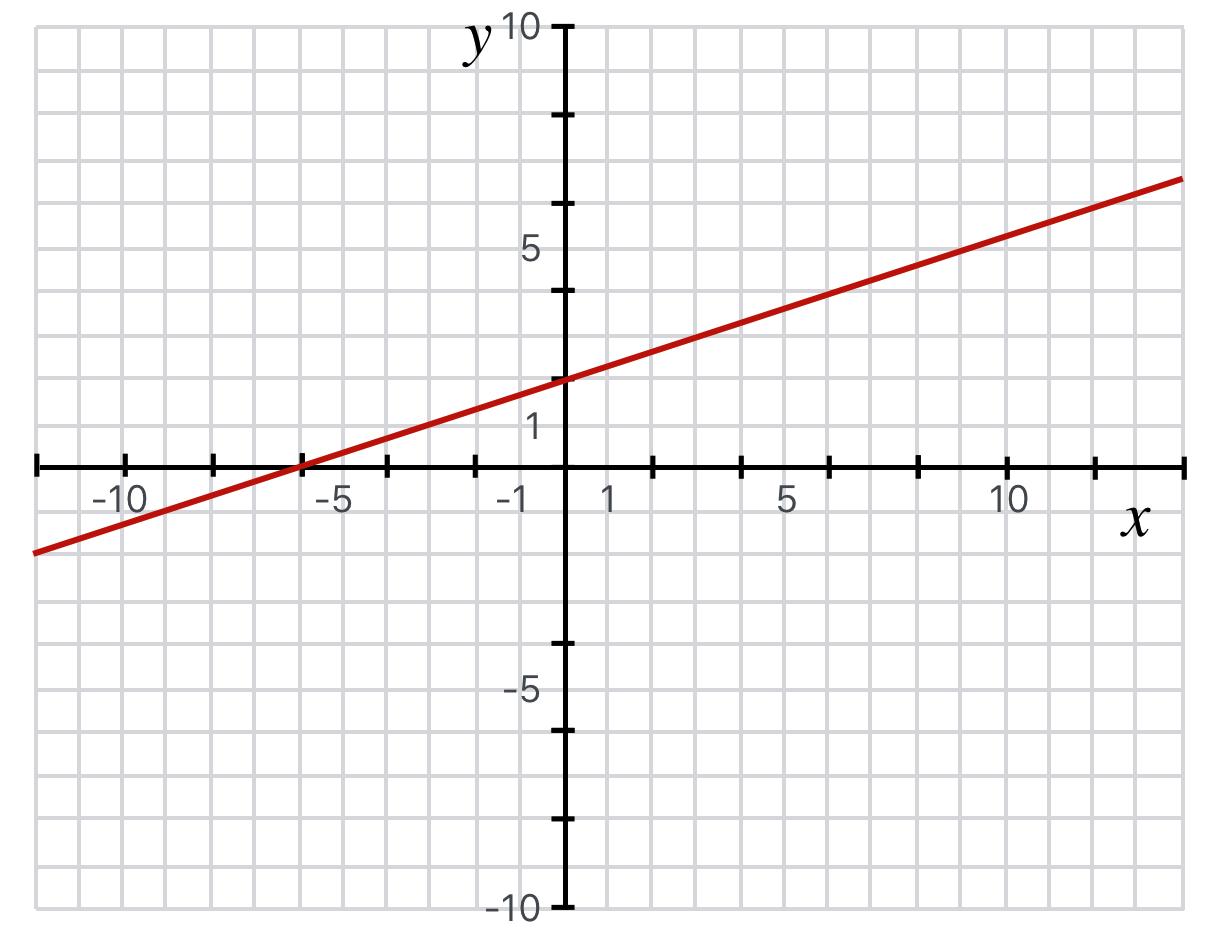

Figure 4.6: \(y=0.5 x + 3\). The dot is the result of graphically “solving” the equation when \(x=8\).

You can see that plugging in the numbers into the formula gives the same result as plotting the function and evaluating it at particular points.

My intention in QS&BB is to tell as much of the story of particles and cosmology as I can but without undue mathematical complexities. I’ll want to refer to very complicated functions, but I’ll plot them. Just like this simple function. Then to “solve” those complicated equations…we’ll just read the graph. The dot above is a visual “solving” of the equation as you saw.

Reading a graph is the same thing as solving an algebraic formula. If you can do that, you can do a lot of complicated physics.

- We will need the occasional square root and exponent. Let’s remind ourselves of a simple manipulation. One more example:

🖋 📓

A question! In the equation \(c = \frac{1}{\sqrt{a+b}},\) can you solve for \(b\)?

Wait. I mean: Please solve for \(b\).

Glad you asked. ;) Sure. I’ll do it like before, annotating each step:

\[\begin{align}

\text{start from a clean beginning:} \;\;\; c &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{a+b}} \\

\text{make the square root disappear:} \;\;\; c^2 &= \frac{1}{a+b} \\

\text{get $b$ upstairs:} \;\;\; c^2(a+b) &= \frac{1}{a+b}(a+b) \\

c^2(a+b) &= 1 \\

\text{work to isolate $b$:} \;\;\; \frac{c^2(a+b)}{c^2} &= \frac{1}{c^2} \\

a+b &= \frac{1}{c^2} \\

b &= \frac{1}{c^2} -a

\end{align}\]

Good job!

It will be no more difficult than this.

Our appetite for algebraic complexity will be very modest. We’ll not encounter formulas that are much more complicated than these. Please (please) convince yourself that you can do the solutions in the right hand column.

🖋📓 \[\begin{align} y &= a\times x = ax \quad &\text{ solve for x to get}\quad x &=y/a \\ y &= x + z \quad &\text{ solve for x to get}\quad x&=y-z \\ y &= a\times x + b = ax + b \quad &\text{ solve for x to get}\quad x&= \frac{y-b}{a} \\ y & = \sqrt{ a+x} \quad &\text{ solve for x to get}\quad x &= y^2 -a \\ y & = \frac{b}{\sqrt{ a+x}} \quad &\text{ solve for x to get}\quad x &= (\frac{b}{y})^2 -a \end{align}\]

(Were you writing? I’ll wait.)

Can you do each of these? Then you’re good: that’s about all that you’ll need to remember of algebra. Just remember the rule. Then…it’s merely a game—a puzzle to solve.

4.6.2 The Powers That Be: Exponents

Instead of “\(y^n\)” some of you might have learned to write: “\(y\)^\(n\).” I’ll stick with my way and I hope you do also.

Once in a while, we’ll need to multiply or divide terms that have exponents, including powers of 10. There are simple rules for this, but let’s figure them out by hand…so to speak. The first thing to remember about exponents is that in a term like \(y^n\), a positive integer \(n\) tells you how many times you must multiply \(y\) by itself. So: \(y^1 = y .\) Here, there’s just one \(y\).

🖋📓

The second thing to remember is that \(y^0 = 1\). There aren’t any \(y's\) in the product and so all that could be there is 1. Armed with that, let’s kick it up a notch.

Suppose I have \(y\times y\). You’d be pretty comfortable calling that “y-squared” and from the above, the number of \(y's\) there are in that product is two. So \(y\times y = y^2.\) If I add another product, then I’d have \(y\times y \times y = y^3.\) Get it? Notice that what we’ve also got in this equation is: \(y\times y \times y = y^2 \times y^1= y^3\) and we’ve just developed our first rule on combining exponents:

\[y^n \times y^m = y^{n+m}.\]

One more time, but different. Another rule recalling that a negative power means “one over…”:

\(x^{-n} = \frac{1}{x^n}.\)

If the same rule for adding exponents works — and it does — then we can multiply factors with powers by keeping track of the positive and negative signs of the exponents.

So here’s an easy one: \(\frac{x\times x \times x}{x\times x} = x\) which you quickly get by crossing out two \(x\)’s in the numerator and the denominator leaving you with one left over.

Or, by using the powers and the rule:

\[\frac{x\times x \times x}{x\times x} = \frac{x^3}{x^2} = x^3 \times x^{-2} = x^{3-2} =x.\]

Now you try it.

🖥️

Please answer Question 1 for points: practice with exponents

One more thing. The powers don’t have to be integers.

Perhaps you’ll remember that square roots can be written:

\[\begin{align*} \sqrt{x} &= x^{0.5} = x^{1/2} \\ \mbox{so:} & \\ \sqrt{9} & = 3 \;\; = \; 9^{0.5} \\ \mbox{or:} & \\ \sqrt{\frac{1}{9}} & = \left(\frac{1}{9}\right)^{0.5} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{9}} = \frac{1}{9^{0.5}} = 9^{-0.5} \\ & = \frac{1}{3} \end{align*}\]

4.6.3 Formulas from your past that might be explicitly useful

I know that you’ve seen most of this somewhere in your past! So return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear. Straight lines, circles, and the areas and circumference of circles and triangles are useful.

4.6.3.1 Equation of a straight line

A straight line with a slope of \(m\) and a \(y\) intercept of \(b\) is generally described by the equation,

\[y = mx+b\]

Figure 4.7: A straight line with a slope of \(1/3\) and a \(y\) intercept of \(2\), so \(y=1/3x+2\).

4.7 Geometry: Vectors, Curves…Formulas From Your Past?

4.7.1 Curves

4.7.1.1 Equation of a circle

We will deal with some functions that would be very hard to evaluate on your calculator. But Descartes’ gift is that I can show you the graph and evaluation can be done by eye, which is in effect solving the equation. We’ll use some simple geometrical relations which I’ll summarize here.

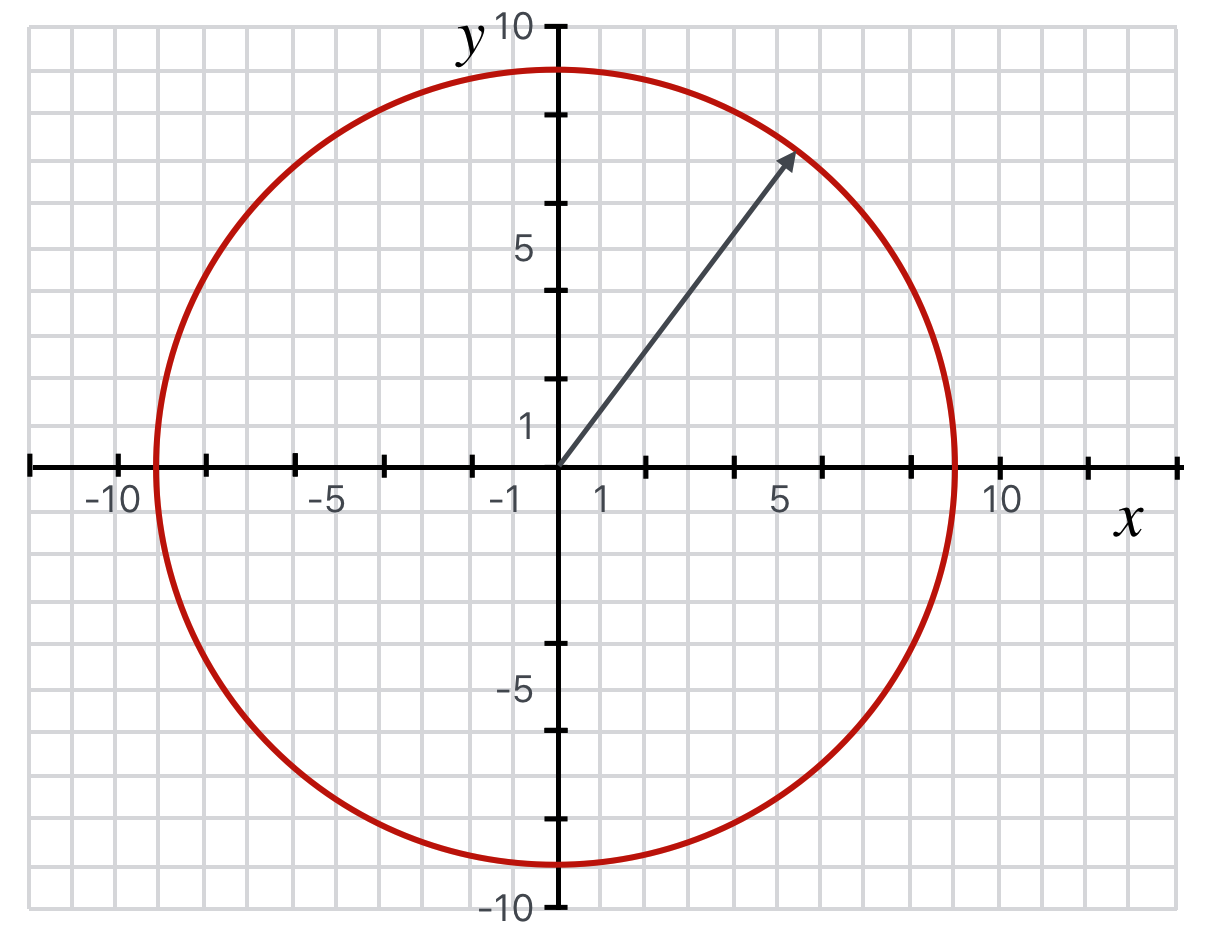

A circle of radius \(R\) in the \(x-y\) plane centered at a \((a,b)\) is described by the equation:

\[(x-a)^2 + (y-b)^2 = R^2.\]

Of course if the circle is centered at the origin, then it looks more familiar as in this figure:

Figure 4.8: A circle centered at the origin described by the equation, \(x^2 + y^2 = 81\). It has radius of \(9\), area \(A= \pi 9^2\), and circumference \(C=2 \pi 9\).

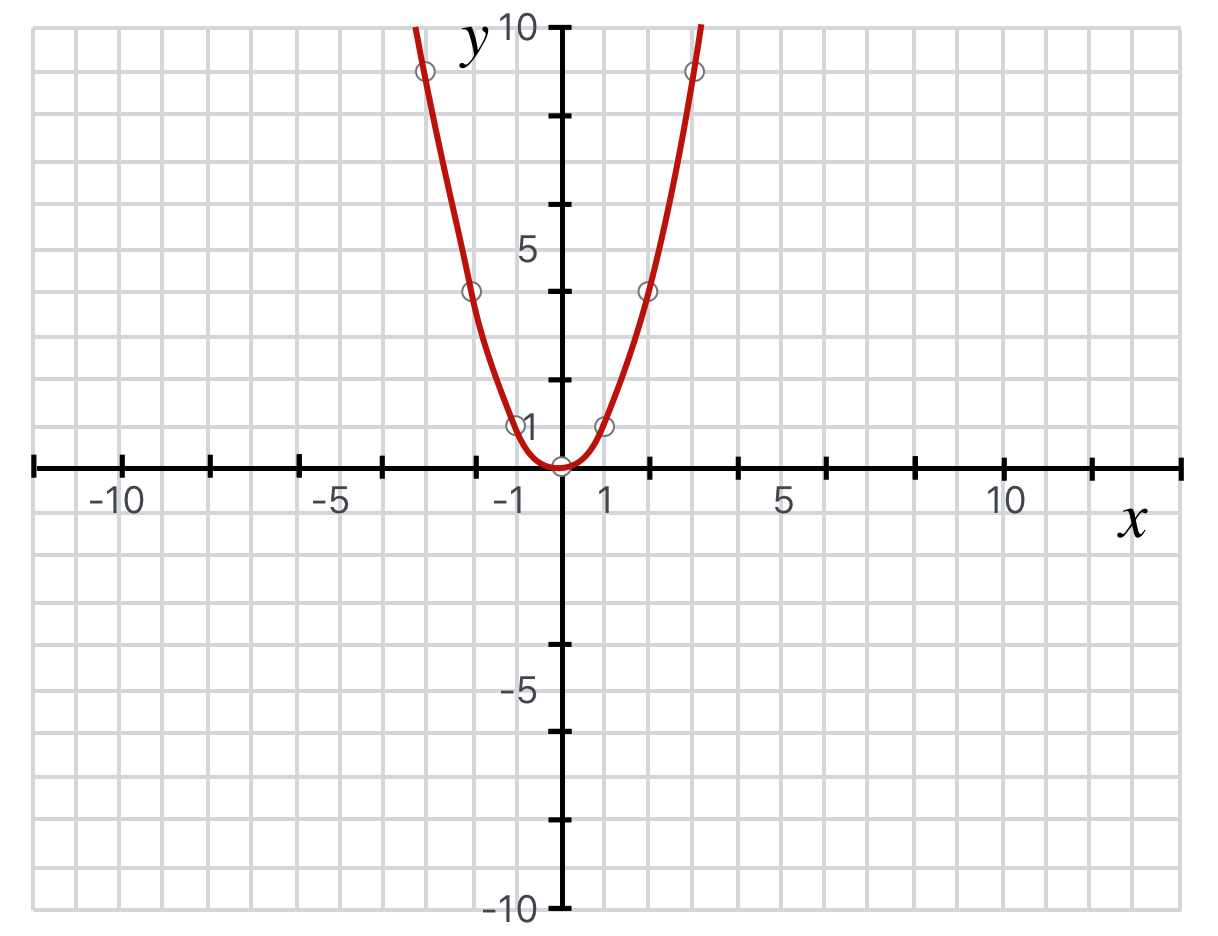

4.7.1.2 Equation of a parabola

A parabola in the \(x-y\) plane facing up with vertex at \((a,b)\) where \(C\) is a constant has the equation,

\[y=C(x-a)^2 + b.\]

Figure 4.9: A parabola satisfying the equation, \(y = 1x^2\).

4.7.1.3 Area of a rectangle

A rectangle with sides \(a\) and \(b\) has an area, \(A\) of

\[A = ab\]

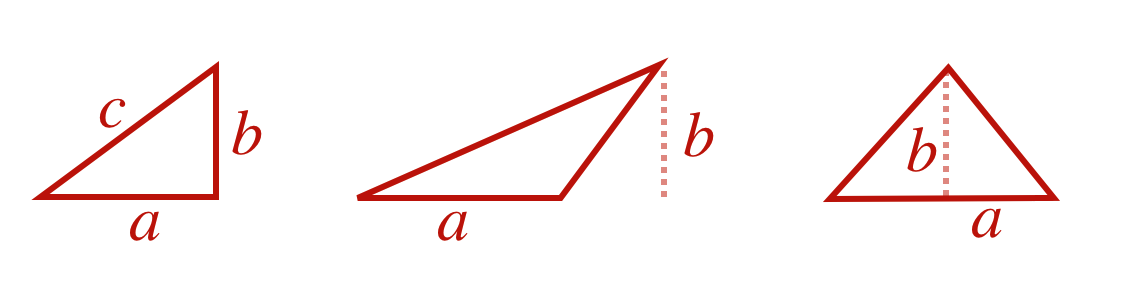

4.7.1.4 Area of a right triangle

A right triangle (which means that one of the angles is \(90\) degrees) with base of \(a\) and height of \(b\) has an area, \(A\) of

\[A= \frac{1}{2} ab.\]

For a right triangle, the base and height are equal to the two legs. But the formula works for any triangle. Here are some examples,

Figure 4.10: Three triangles, all with the same areas.

4.7.1.5 Area and circumference of a circle

Circles will involve \(\pi\) which is an irrational number which we’ll never need precision better than “March 14th,” \(\pi = 3.14\). And, yes, the story that in 1897 Indiana’s General Assembly tried to change the value to \(\pi_{\text{Indiana}}=3.0\) in order to simplfy calculations. Mathematicians and engineers around the state had collective heart palpitations. It disappeared quickly.

For a circle of radius \(R\), the area, \(A\) is

\[A=\pi R^2\]

and the circumference, \(C\) is

\[C = 2\pi R\]

4.7.2 Pythagoras’ Theorem

For a right triangle (like the left hand triangle above), the hypotenuse, \(c\) is related to the lengths of the two sides \(a\) and \(b\) by the Theorem of Pythagoras:

\[c^2 = a^2 + b^2.\]

And, no. He didn’t invent it and it’s been proven many, many different ways.

4.7.3 The quadratic formula

We might run across a particular polynomial, which you’ve also probably seen before:

\[f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c. \nonumber\]

It’s an “order 2” polynomial, which means that there are two values of \(x\) that qualify as “solutions”: the values of \(x\) that when substituted make the function be zero. You could plot the function and find what \(x\) values the curve passes through the \(x-\)axis, or you could rely on the time-honored recipe:

\[x_{1,2} = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 -4ac}}{2a} \nonumber\]

Figure 4.12: You can stop here. The rest is for reference.

4.8 A Gentle Review 2: Skills for Only a Few Times

There are a handful of skills that will sometimes come up, but not every lesson. I have in mind here reading log-plots, unit conversions, approximating functions, simple graphical vector manipulations, and a few more geometrical relationships.

4.8.1 Log-Log and Semi-Log Plots

Wait. LOGARITHMS!!? NO!

Glad you asked. Calm down. There will be only a couple of times when I’ll ask you to read a plot…meaning identify a point on a curve in which the axes are not linear (1, 2, 3, 4…) but logarithmic (10, 100, 1000…). No functional manipulations. Just interpretation.

Sometimes it will be useful to plot functions or data that range over a wide scale, maybe even many powers of 10. I want to make use of log-log plots and semi-log plots because it’s about the only way to display functions that range over many orders of magnitude. So we’ll use them as a tool, but we’ll never actually evaluate a logarithm. Here’s an example.

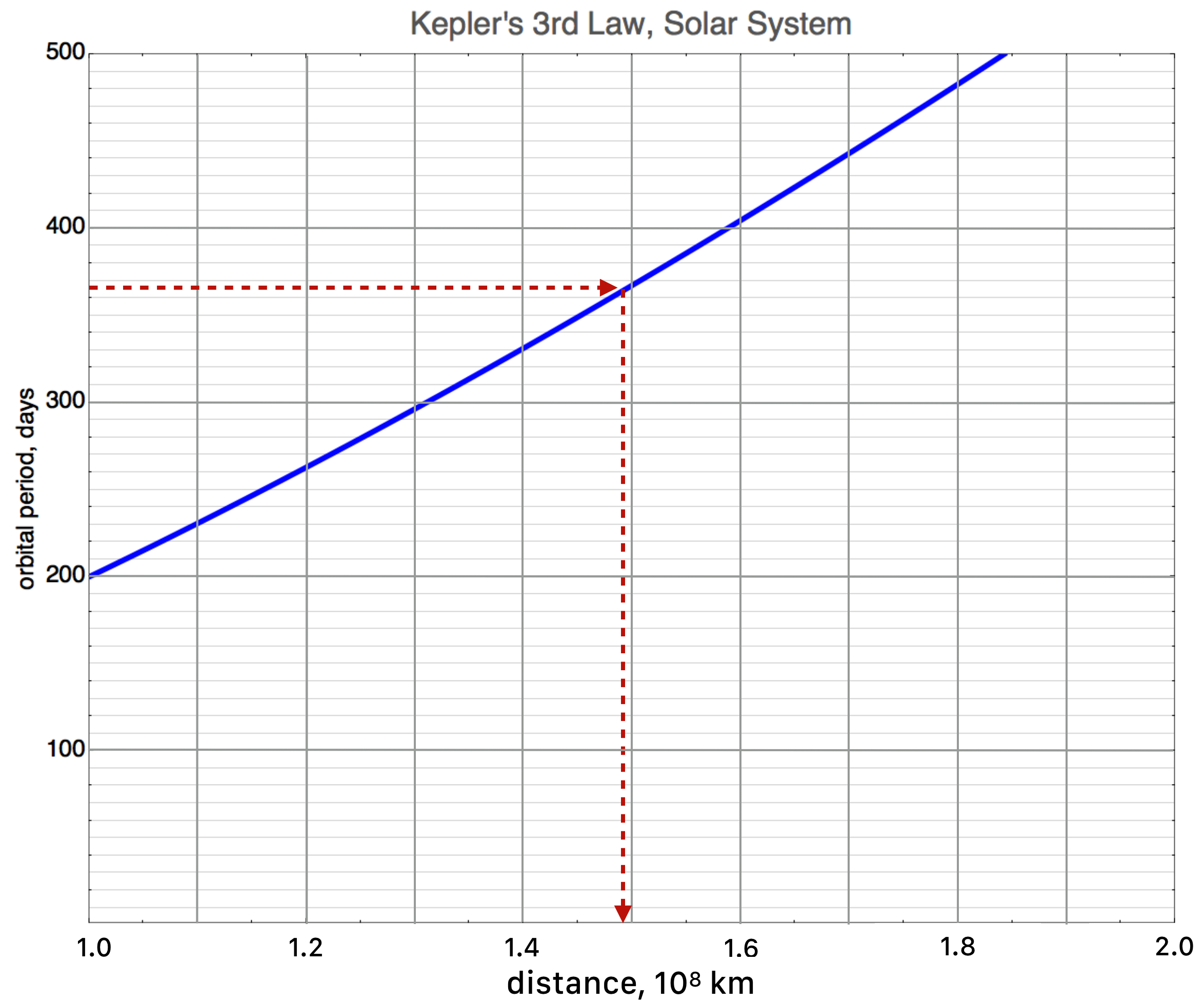

We’ll learn that there is a relationship between the time it takes for a planet to orbit the sun (its “period”) and the distance away that its orbit is from the center of the sun. Here it is for a slice of distances. The graph displace orbital period in units of days versus the distance from the sun in units of 100,000,000 kilometers. So the left hand “origin” is at 100,000 km, then the next big tick mark is at 110,000,000 km and the next (labeled) tick mark is at 120,000,000 km. That’s a lot of zeros, so I labeled the horizontal axis as units of \(10^8\) km.

Figure 4.13: CAPTION

If I asked you to find the distance earth, which has a period of 365 days, is from the sun, you’d look at the vertical, period axis, dig into the tick marks, and figure out where to find 365 on the vertical axis, right? I’ve kind of done that — what your finger would probably do — and I find that the horizontal, light lines are at every 10 days and the tick marks are at every 20 days, so I’d find 365 at about where the horizontal arrow is. Using the model — solving the equation that relates period to distance — means simply finding the point on the curve and reading down to the distance. Going down from the curve, it would hit at about \(1.5 \times 10^8~\)km. That’s about right.

If I asked you to do the same thing for Venus, but the other way around you could do that.

🖋 📓

If Venus is \(1.07 \times 10^8\) km can you convince yourself that its orbital period is about 226 days?

How about Mars? Its period is about 687 days. Certainly the model (the blue line) should describe Mars. How about Mercury? Its period is 87 days and it’s distance is \(0.58 ]\times 10^8\) km. How about Neptune? It’s period and distance are 60,200 days and \(44.8\times 10^8\) km. None of these fit on the graph. So this plot is pretty useless as a guide to the solar system. Don’t despair. There’s a way.

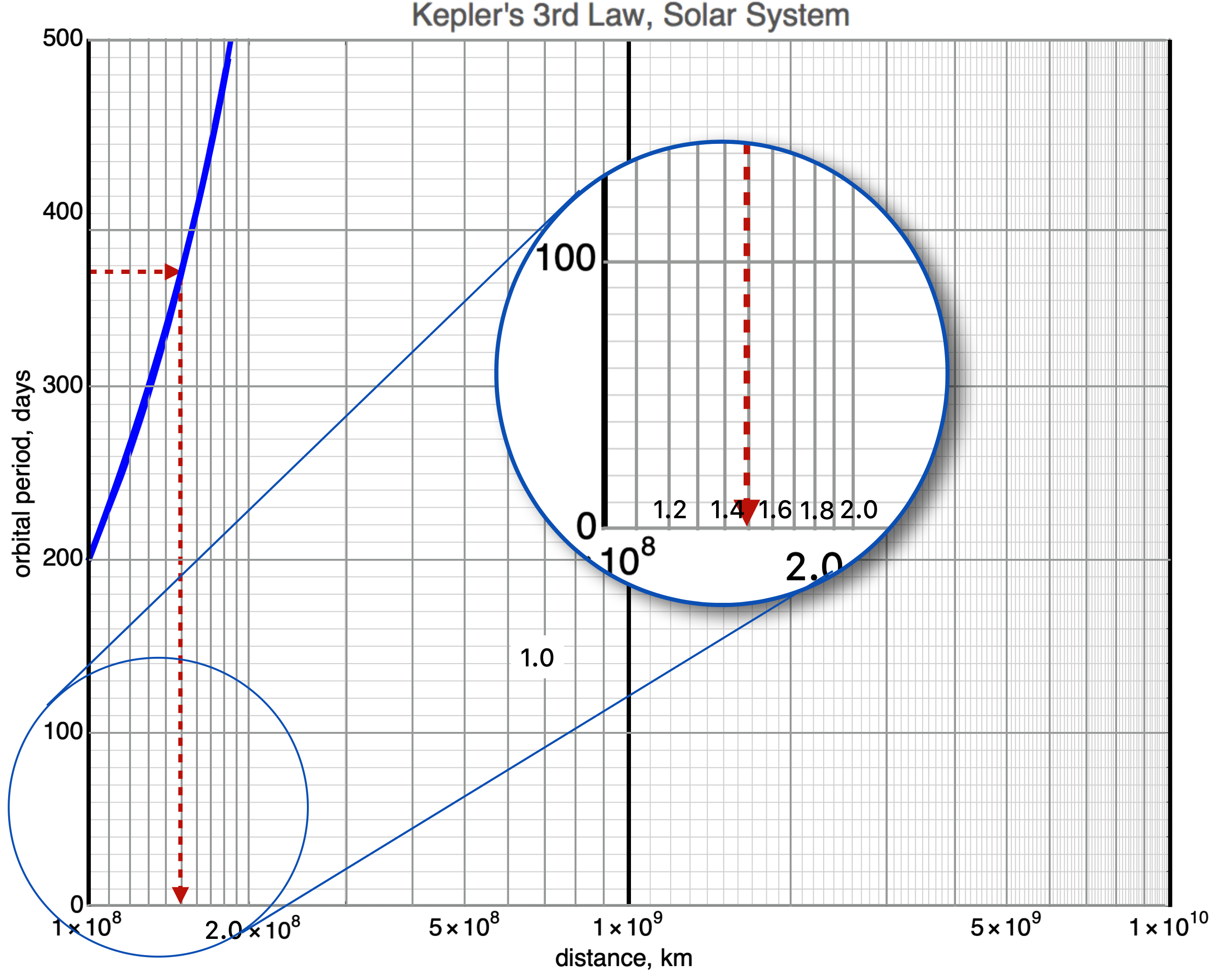

This is where a log-linear or log-log plot saves the day. In a log plot the axes are labeled by powers of 10, so 1, 2, 3… and so on, standing for \(10^1, 10^2, 10^3\). This power relation distorts the curve from presentation on a linear scale pair, but it’s not wrong, just different. Let’s do that for our solar system for the horizontal axis.

Figure 4.14: CAPTION

In this figure, the dark, black vertical lines tell you the \(1\times 10^8, 1\times 10^9, \text{ and } 1\times 10^{10}\) km marks. The vertical gray lines indicate the $ 2,3,4,5,6,7,8,910^{8,9,10}$ km marks. The circular inset breaks down the \(10^8\) region to that of the linear horizontal plot up above. Notice that the red, dashed lines mean what they did in the first plot: 365 days for Earth’s period on the vertical axis and about \(1.5 \times 10^8\) km for Earth’s distance from the center of the sun on the horizontal axis.

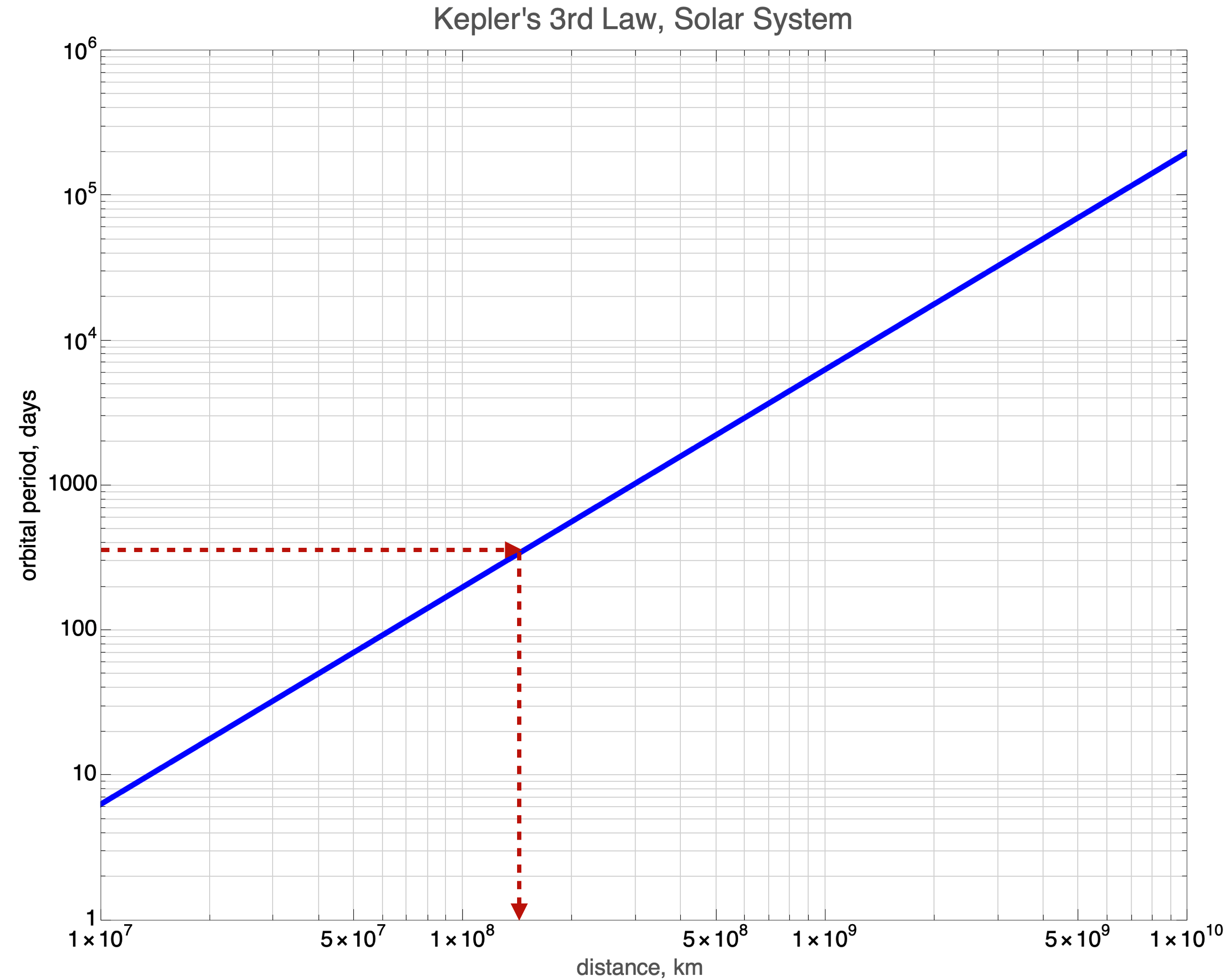

But we still can’t represent much of the solar system in one plot, so we must also make the vertical axis logarithmic. A “log-log” plot, whereas the previous is a “linear-log” or “semi-log” plot. Here it is, the model of orbiting planets around our particular Sun. Earth is again represented as the red, dashed lines and now we can evaluate the periods and distances for many more planets.

(#fig:solarsystem.png)Kepler’s 3rd law for anything orbiting in our solar system: the period versus the distance from our sun.

This covers 6 orders of magnitude in days and 4 orders of magnitude in kilometers.

🖋 📓

Jupiter is \(483 \times 10^6\) miles from the sun. What’s its period in days? You’ll want to consult Mr Google to get km. The period is about 4000 earth days, about 12 earth years.

4.8.2 Unit Conversions

Numbers are just numbers without some label that tells you what they refer to. Not all numbers have to refer to something, a pure number is a respectable mathematical object—prime numbers for example have been a topic of research for centuries. Irrational numbers — those that can’t be expressed as a ratio of whole numbers, like \(\pi\), — are likewise objects with no necessary relationship to…“stuff” in our world. But they keep coming up in nature, so we warm to them.

We’re mostly concerned with numbers that measure a parameter or count physical things and they come with some reference unit (“foot”) that is a customary way to compare one thing with another. Of course not everyone agrees on the units that should be used. Wait. Let me restate that: there’s THE WHOLE WORLD that agrees on one set and then there’s the United States that marches to its own set of units. Thinking of you, “feet,” “pounds,” and “Fahrenheit.”

I’ll not use Imperial units (feet, inches, pounds, etc.) very much, except to give you a feeling for something that you’ve got an instinct for…like the average height of a person or a single story house. We’ll use the metric system, in particular the MKS, aka SI units1 in which the fundamental length unit is the meter (about a yard), the fundamental mass unit is the kilogram, and the fundamental temperature unit is the Celsius. I’ll generically refer to these as “MKS” (for meter-kilogram-second) or “metric units” without being too fussy about the fancier names, like SI.

It’s small comfort that we’re all in agreement on seconds, minutes, and hours and its base-60 origins. In 1793 the French tried to change that to “decimal time” with a 10-hour day, 100 minutes in an hour, and 100 seconds in a minute and so on, but it didn’t catch on.

Just like an exchange rate in currency, so many euros per dollar, we’ll need to be able to convert, among many different units. All the time.

Wait. That can be pretty involved.

Glad you asked. You’re right and it can be a way to make mistakes and get all wrapped up in the conversion that you lose track of the physics. You know what? I’ll not care. I’ll give you little conversion engines that will do any unit conversion that you need to do. Just let me show you what it means and then we’ll be pretty low-key about this.

Having said that, we should review how this works—what will be behind any tool that does unit conversion.

Let’s get our bearings. What’s the height of an average male. Mr Google tells me that’s about 5’10”. How many inches tall is our average male? Here’s the pre-QS&BB thought-process you’d use to calculate this.

Three steps:

- A single foot is \(12\) inches.

- So, \(5\) feet is \(5 \times 12\) = \(60\) inches

- and the combination is \(60 + 10 = 70\) inches.

…which you could almost do in your head, which, by the way, averages in circumference at about 22 inches. You’re welcome.

But this simple, almost intuitive calculation uses a more general conversion from one unit to another through a tricky multiplication by the number 1. Can you multiply by 1? Then you can convert units like a champ.

🖋📓

Here’s a cute way to write 1 by starting with some basic conversion translation like \(12 \text{ inches} = 1 \text{ foot}.\) Then you make “1” out of it:

\[\begin{align*} 12 \text{ inches} &= 1 \text{ foot} \\ 1 &= \frac{1 \text{ foot}}{12 \text{ inches}} \\ \text{ or} & \\ 1 &= \frac{12 \text{ inches}}{1 \text{ foot}} \end{align*}\]

All unit manipulations this conversion factor and all you have to do is figure out which version to insert.

Armed with this, we can do the conversion of 5 feet to inches.

\[

\begin{align*}

5 \text{ feet} = 5 \text{ feet} \times 1 &= 5 \text{ feet } \times \frac{12 \text{ inches}}{1 \text{ foot}} \\

5 \text{ feet} \times 1 &= 5\times 12 \text{ inches} = 60 \text{ inches} \\

5 \text{ feet} &=60 \text{ inches}

\end{align*}

\]

Notice that we treat units like algebraic terms and can cancel them as if they were symbols or numbers: the “feet” cancel above. That’s the neat thing. If you set up the conversion factor right, the units will multiply and divide along with numbers so you can always see that you get what you want.

While this is a particularly simple conversion, sometimes we’ll need to do some which are either more complicated, or use units that maybe you’re not very familiar with. I won’t be so pedantic usually, but hopefully you get the point!

Let’s work out an example. Something you can use at a party. I first worked this out for a class when I was in Geneva, Switzerland working at CERN. It was July 4, 2010, which was just another Sunday over there. The United States came into existence on July 4, 17762 which was \(2010-1776 = 234\) years ago.

🖋📓

a

Question! How How many seconds had the United States been around if we start from midnight on July 4, 1776?

Glad you asked. We need a handful of 1’s here:

>

\[\begin{align*}

1 &= \frac{1 \text{ minute}}{60 \text{ seconds}} = \frac{60 \text{ seconds}}{1 \text{ minute}} \\

1 &= \frac{24 \text{ hours}}{1 \text{ day}} = \frac{1 \text{ day}}{24 \text{ hours}} \\

1 &= \frac{1 \text{ hour}}{60 \text{ minute}} = \frac{60 \text{ minute}}{1 \text{ hour}} \\

1 &= \frac{1 \text{ year}}{365 \text{ day}} = \frac{365 \text{ day}}{1 \text{ year}}

\end{align*}\]

Now it’s a matter of just multiplying by the right combinations of “1” as many times as necessary to get where you want to be.

>

\[\begin{align*}

234 \mbox{ year} &= 1 \times 1 \times 1 \times 1 \times 234 \mbox{ year} \\

&= \frac{60 \text{ seconds}}{1 \text{ minute}}\frac{60 \text{ minute}}{1 \text{ hour}}\frac{24 \text{ hours}}{1 \text{ day}}\frac{365 \text{ day}}{1 \text{ year}} \times 234 \text{ year}\\

&= \frac{31,536,000 \text{ second}}{\text{year}} \times 234 \\

234 \mbox{ year} &= 7.38 \times 10^9 \text {seconds}

\end{align*}\]

Good job!

There are a few of things to notice here. First, that’s a lot of seconds! Second (get it?), if we’d known that there are \(3.154 \times 10^7\) seconds in a year we could have started with that and had just one factor of 1. And finally…“3.154”? Does that sound familiar to anyone?

Quite by accident, the number of seconds in a year is close to the first few digits of \(\pi = 3.14159...\) times \(10^7\) and so we often say that the number of seconds in a year is about “\(\pi \times 10^7\).”

Just as a memory device. You’re welcome.

4.8.3 Vectors, 2

Some quantities in nature have a magnitude (like a temperature) and a magnitude and a direction, like a velocity. 60 mph north does not result in the same trip as 60 mph east, so direction and speed both matter. I think that the most intuitive vectors are those associated with a distance in space and a force, so in this survey I’ll concentrate on those two. We’ll meet many other vectors throughout QS&BB, but I’ll highlight their vector natures when we come to them. As I’m writing this, the World Series in 2018 is about to start, so let’s think about a baseball diamond.

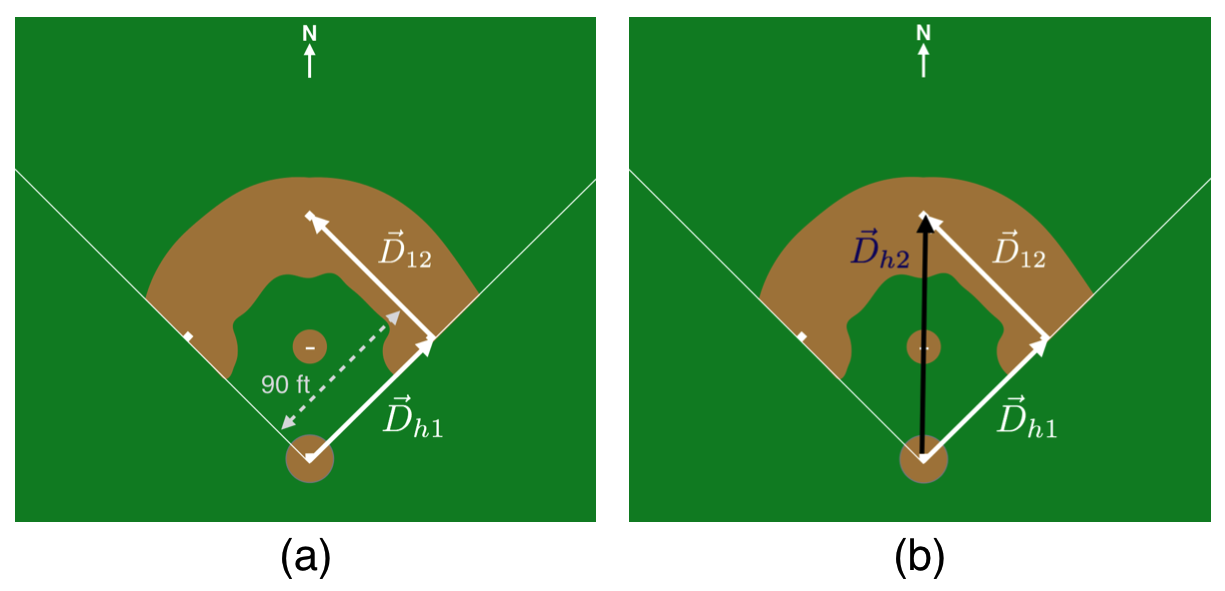

In baseball, the distance between the bases is 90 feet and according to the rules, a runner must follow the bases in order. So to go from home plate to second base, the path that’s followed must be according to the two arrows in this figure. This situation is shown in the (a) below. Here, Frank has hit a double and being a good sport has indeed taken the appropriate path to second base.

Figure 4.15: Figure (a) shows the appropriate path to second base. (b) Shows an illegal path to second base.

🖋📓 Notice that the total path is represented by two vectors,

\(\vec{D}_{h1}\) and \(\vec{D}_{12}\).

There are many ways to represent the combination of magnitude and direction for a vector. When marking with a pencil, one would typically draw an arrow over the symbol as I’ve done here. In a fancy printed version, the \(D\) would be bold, D. We must also adopt a coordinate system in every situation so that the direction can be concretely specified. You might have used an \(x-y\) coordinate system, but that’s not necessary. Here the ballpark has been layed out with north being directly to second base from home plate—that’s a coordinate system.

In order to represent all of the information in a vector, we’ll be satisfied with either a graphical representation—a labeled picture—or something else. Here’s an example. If Ossie hits a single, we could represent his trajectory vector from home to first base as

\[\vec{D}_{h1} = 90 \text{ ft NE}. \nonumber\]

The formal name for a vector in regular space is displacement and the formal name for the magnitude of a displacement vector is length or distance so the vector \(\vec{D}\) is the displacement and 90 ft is the length.

Maybe not the way you might have seen a vector displayed, but it’s perfectly okay. It encodes the length (90 feet) and the direction (northeast) in one thing.

Next up, Dewey smacks a double, and so his vector would be

\[\vec{D}_{h1} + \vec{D}_{12}. \nonumber\]

Chester is up next and realizes that the shorter distance from home plate to second base is straight north across the diamond over the pitcher’s mound, which is shown in (b). While he hit the ball to the warning track, after that day he didn’t play long on that team since he took that shorter path and was called out for not following the rules. What’s okay in mathematics is not necessarily okay in baseball.

Chester is right, though. Before he was called out, he correctly navigated what is actually the vector sum of two vectors:

\[\vec{D}_{h2 } = \vec{D}_{h1} + \vec{D}_{12}. \nonumber\]

Both the left hand and the right hand of that equation are equivalent in that they both connect home plate with second base.

🖋📓

Question! Earlier Earl was at bat and hit a ground ball to the shortstop but he fell down halfway to first base. How does his displacement compare to Ossie’s in vector notation?

Glad you asked. Before his embarrassment, Earl was running in the same direction that Ossie ran—and thousands of ball-players before them. However his vector would be:

>

\[\vec{D}(\text{Earl}) = 0.5 \vec{D}(\text{Ossie}) = 45\text{ ft NE},\]

an arrow pointing from home plate halfway to first base.

Good job!

Interactive: 3.5; 2018.10.23; 16:51 Dewey was also unlucky and after Chester was called out he tried to steal third base from second base, but fell down 1/3 of the way. What’s the vector that represents his short trip?In QS&BB we’ll make a lot of use of the handy arrow symbol: \(\rightarrow\). The length of the arrow represents the magnitude and of course the orientation and the head of the arrow represent the direction. Arrows can be \(\longrightarrow\), or short \(\rightarrow\), pointed in different directions, \(\nwarrow\), \(\leftarrow\), \(\nearrow\), etc. Very handy.

The magnitude can mean many things, depending on the physical quantity being represented. Some of the vectors that we’ll meet are displacement, velocity, momentum, force, electric field, magnetic field, and angular momentum.

A few useful things from this figure:

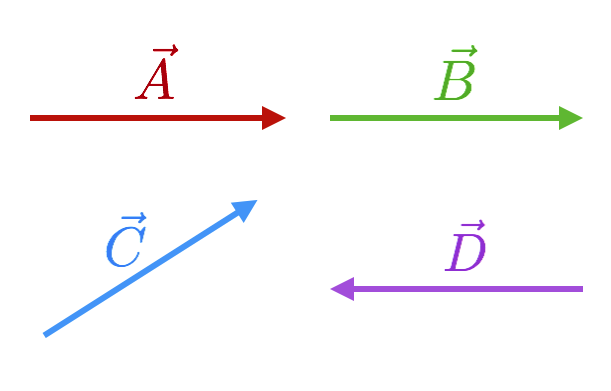

Figure 4.16: Random vectors, all of the same length.

Two vectors, \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) are said to be equal if they are both the same length and point in the same direction so

\[\vec{A} = \vec{B}. \nonumber \]

Vector \(\vec{C}\) is the same length as both \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) but

\[\vec{C} \ne \vec{A} \text{ and } \vec{C} \ne \vec{B} \nonumber \]

because its direction is different. Finally, the negative of a vector is that same vector pointing in the opposite direction. So for example,

\[\vec{A} = - \vec{D}. \nonumber \]

4.8.3.1 Vector addition in one dimension

Generally, we’ll treat a vector quantity as an arrow pointing in some direction and a length that represents its magnitude. Sometimes a vector can represent an actual path in space (like meters, feet, and so on) where it’s easy to imagine what it means. We do this all the time on maps with a scale showing that some map-distance (an inch) can stand for a real-world distance (“1 inch = 1 mile”).

But, sometimes a vector doesn’t represent a length in space, but some other physical quantity, like a force or a velocity. This can be complicated since you’re drawing an arrow that has a “regular” length, but you mean it to be something else, like a force. But, it still works geometrically (the arrow still points in space) and we just use a different scale. Let’s do something simple.

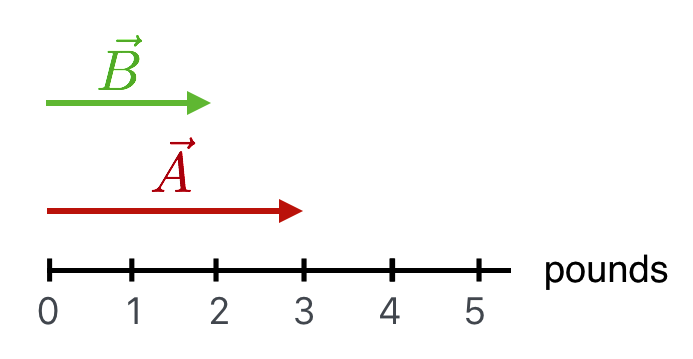

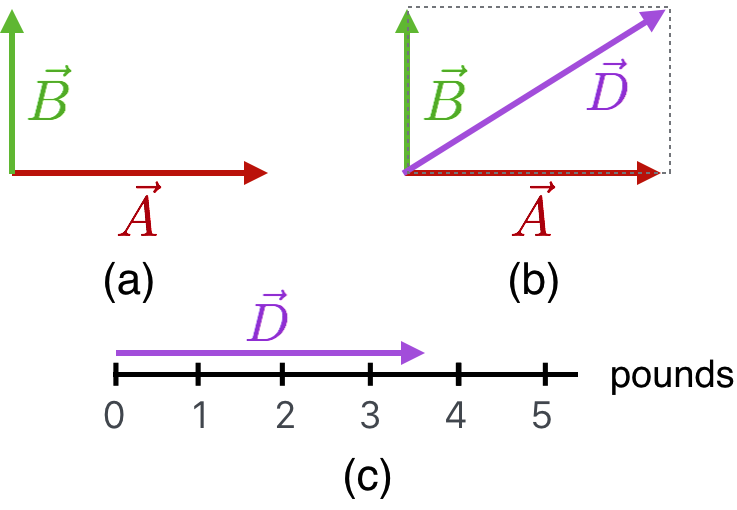

🖋📓

In the next figure are two vectors that now represent forces, so their lengths have the units of pounds. I’m obligated to provide a scale and you can see it. Vector \(\vec{B}\)’s length has a magnitude of 2 pounds and \(\vec{A}\) is one pound more.

Figure 4.17: Two force vectors with lengths 2 and 3 pounds.

If \(\vec{A}\) corresponds to Muriel pulling the leash on her reluctant and enormous dog and vector \(\vec{B}\) corresponds to Earl’s ability to also pull, then the two of them together can pull with the obvious 5 pounds.

Figure 4.18: CAPTION

This is our first vector addition problem. The total vector force that the two of them can exert is in pictures above and in symbols

\[\vec{C} = \vec{A} + \vec{B} = \vec{B} + \vec{A} .\] Here’s the rule: We constructed \(\vec{C}\) by connecting the tail of one vector with the head of the other. Keep that in mind, even though it’s pretty obvious when everything is along one direction.

4.8.3.2 Vector addition in two dimensions, the head to tail way

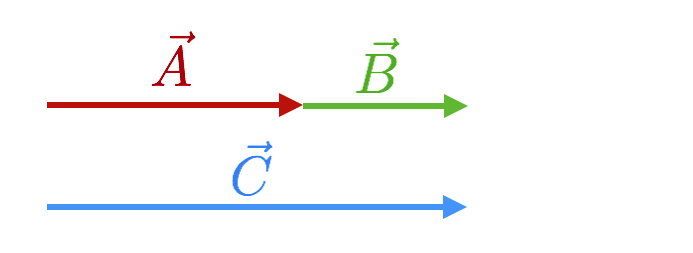

Here’s a different combination of vectors, which looks more like Chester’s baseball career’s embarrassing final act. Here, we have two vectors that have the same lengths on your screen, but now their lengths represent displacement (both a distance and a direction). They look like the force vectors and their lengths on your screen are the same, but the units are different: \(\vec{A}=3\) blocks and \(\vec{B}=2\) blocks.

🖋📓

Figure 4.19: CAPTION

This situation represents a trip through city blocks on the sidewalk: (a) going east \(\vec{A}\) and then north, \(\vec{B}\). Equivalently, (b) represents a trip from the same starting point to the same ending point by cutting across a park, \(\vec{D}\). That third vector is gotten by doing the same tail-to-head manipulation as we did in one dimension. Of course, you’d create that third vector by just walking straight across the park. \(\vec{D}\) is equivalent to the combination of \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\), which is to say

\[\vec{A} + \vec{B} = \vec{D}\]

Obviously, it’s useful to figure out whether the diagonal path is shorter than the sidewalk paths (thats’ clear by looking) and just how much shorter it is. For that, we need the scale. Let’s use the standard notation that the length (or “magnitude”) of a vector is \(\lvert\vec{V}\rvert\). So here \(\lvert\vec{A}\rvert = 3\) blocks and \(\lvert\vec{B}\rvert = 2\) blocks.

🖋📓

a

Question! In the figure, how much shorter is cutting across the park as compared to traveling on the sidewalk?

Glad you asked. Obviously the sidewalk journey is \(3 + 2 = 5\) blocks. What’s the length of \(\vec{D}\)? We can do this two ways. One way is to look at the triangle in (b) and remember Pythagoras’ Theorem.

>

\[\begin{align*}

\lvert \vec{D}\rvert^2 &= \lvert \vec{A}\rvert^2 + \lvert \vec{B}\rvert^2 = 3^2 + 2^2 = 9 + 4 = 13 \\

\lvert \vec{D}\rvert &= \sqrt{13} = 3.6 \end{align*}\]

>

Or we can use the scale, as in (c)…construct \(\vec{D}\) with the head-tail rule and then just transplant it to the scale and see that its length is indeed a little more than 3 and a half. Or, somehow move the scale like a ruler and measure the length of \(\vec{D}\).

>

Either way, it’s shorter to cut across the park by almost a block and a half. But you sort of knew that.

Good job!

4.8.3.3 Vector addition in two dimensions, the parallelogram way

Here’s another situation.

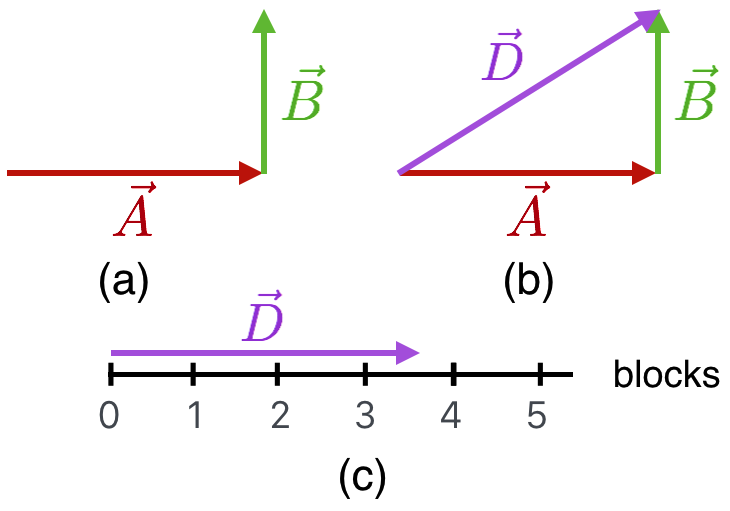

🖋📓

Figure 4.20: CAPTION

The figure is sort of the same, but means something different. First, the scale says pounds, so it’s two forces \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) but now they’re oriented differently as shown in (a). It seems that Muriel and Earl were unable to get their acts together and so they’re pulling on the dog’s collar at right angles to one another.

So their total pull here is going to be less than 5 pounds and will be some total amount that’s oriented between the two. The (b) figure shows another way to add vectors as a manipulation. Instead of tail to head, (b) shows a placeholder parallelogram drawn in dashed outline and the sum of the two vectors is the diagonal. Of course it’s the same vector you’d get if you’d transported \(\vec{B}\) horizontally to the head of \(\vec{A}\) and added them as before. So this is actually an alternative way to construct vectors sums: the head-to-tail way or the parallelogram way.

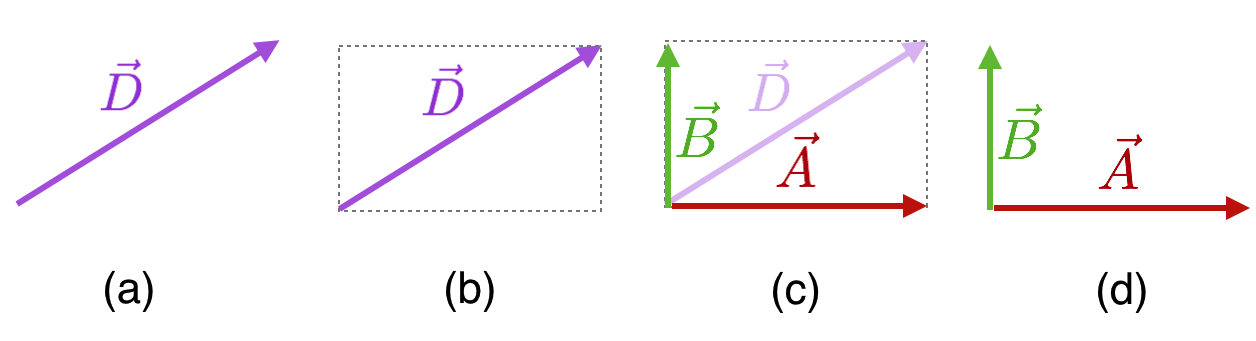

4.8.3.4 Decompose a vector

An inverse of the process of adding two vectors is called resolving or decomposing a vector into its components. This figure shows the steps and is literally the parallelogram addition-method done backwards!

Figure 4.21: The successive steps involved in ‘resolving’ a vector into its perpendicular components.

Let’s decompose vector \(\vec{D}\) into components along the horizontal and vertical directions (it could be any two directions and they need not be perpendicular). The way to construct this is to add a placeholder parallelogram — usually a rectangle — with the original vector across a diagonal. Then the sides become the two decompositions: the vector components. In both of these cases we’re doing:

\[\vec{D} = \vec{A} + \vec{B}. \nonumber\]

Here going from left to right (decomposition of \(\vec{D}\)) and just before, going from right to left (addition of \(\vec{A} \text{ and } \vec{B}\)).

🖋📓 Subtraction of vectors is easy, but requires some thought. In order to construct

\[\vec{A} - \vec{B} = \vec{D} \nonumber\]

We absorb the subtraction sign into the direction designation of \(\vec{D}\) and make a new vector, \(\vec{E} = -\vec{D}.\)…and then add them. This shows the whole sequence of \(\vec{A}-\vec{B} = \vec{A} + \vec{E} = \vec{D}\):

Figure 4.22: The sequence involved in calculating \(\vec{A} - \vec{B} = \vec{D}\)

That is everything we’ll need for any vectors that come along in QS&BB!

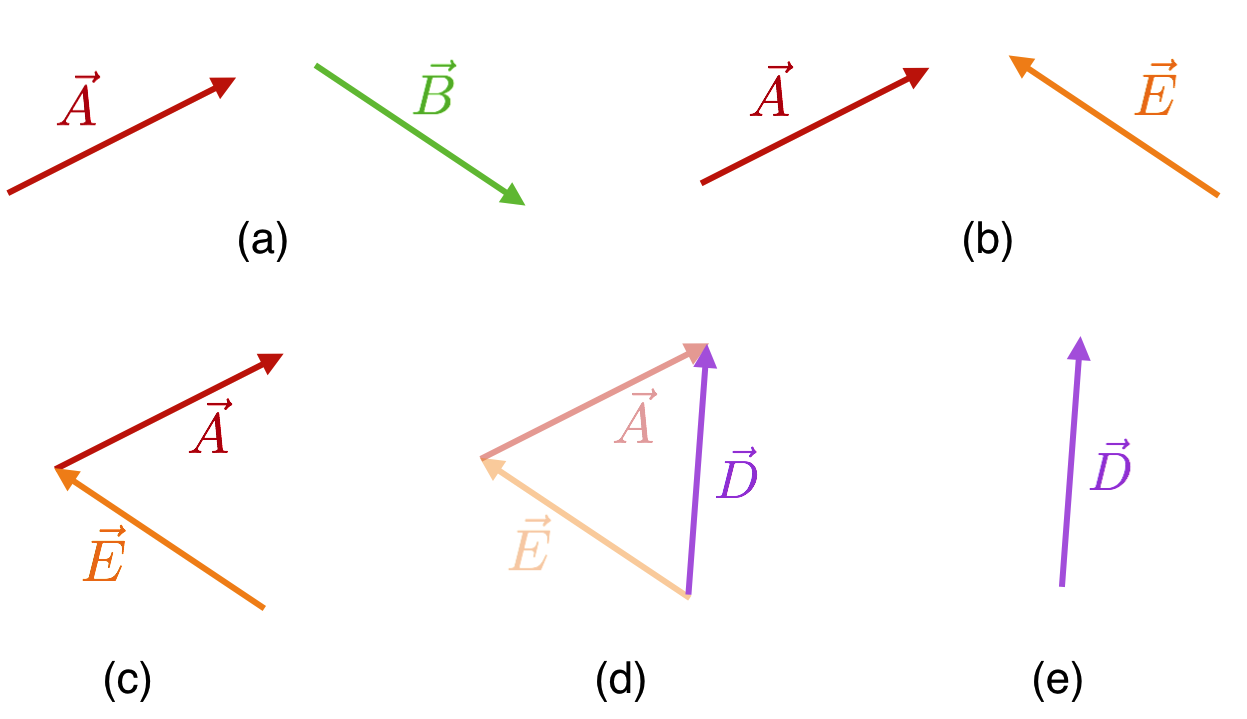

4.8.4 Approximating Functions

🖋📓

One skill we’ll need a couple of times is to be able to look at a function and estimate its form for extreme conditions. Here’s what I mean. Look at this perfectly fine function:

\[y(x) = \frac{a}{b+x}. \nonumber\]

We’ll ask this question of a function often:

What is \(y\) if \(x>>b\)

or what is \(y\) if \(x<<b\)?

Here’s the thought process you’d go through to answer these questions. For the first one, if \(x\) is very much larger than \(b\) then that’s nearly asking the question, “What is \(y\) if \(b = 0\)?” which is the extreme of noting that if \(b\) is really tiny compared to \(x\) then it’s almost as if \(b\) isn’t there are all. We’d get:

\[y(x>>b) \approx \frac{a}{x} \nonumber\]

The other extreme would lead you to say to yourself, “If \(b\) is huge compared to any \(x\), then it’s almost as if \(x\) isn’t there at all.” So:

\[y(b>>x) \approx \frac{a}{b} \nonumber\]

This kind of analysis can lead to useful insight to the physics of a particular model. But we almost always want to look at a graph, like here, for the special case in which \(a\) and \(b\) are both 1:

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{1+x} \nonumber\]

For a moment, let’s concentrate on this function for only positive values of \(x\). Then the function looks like this:

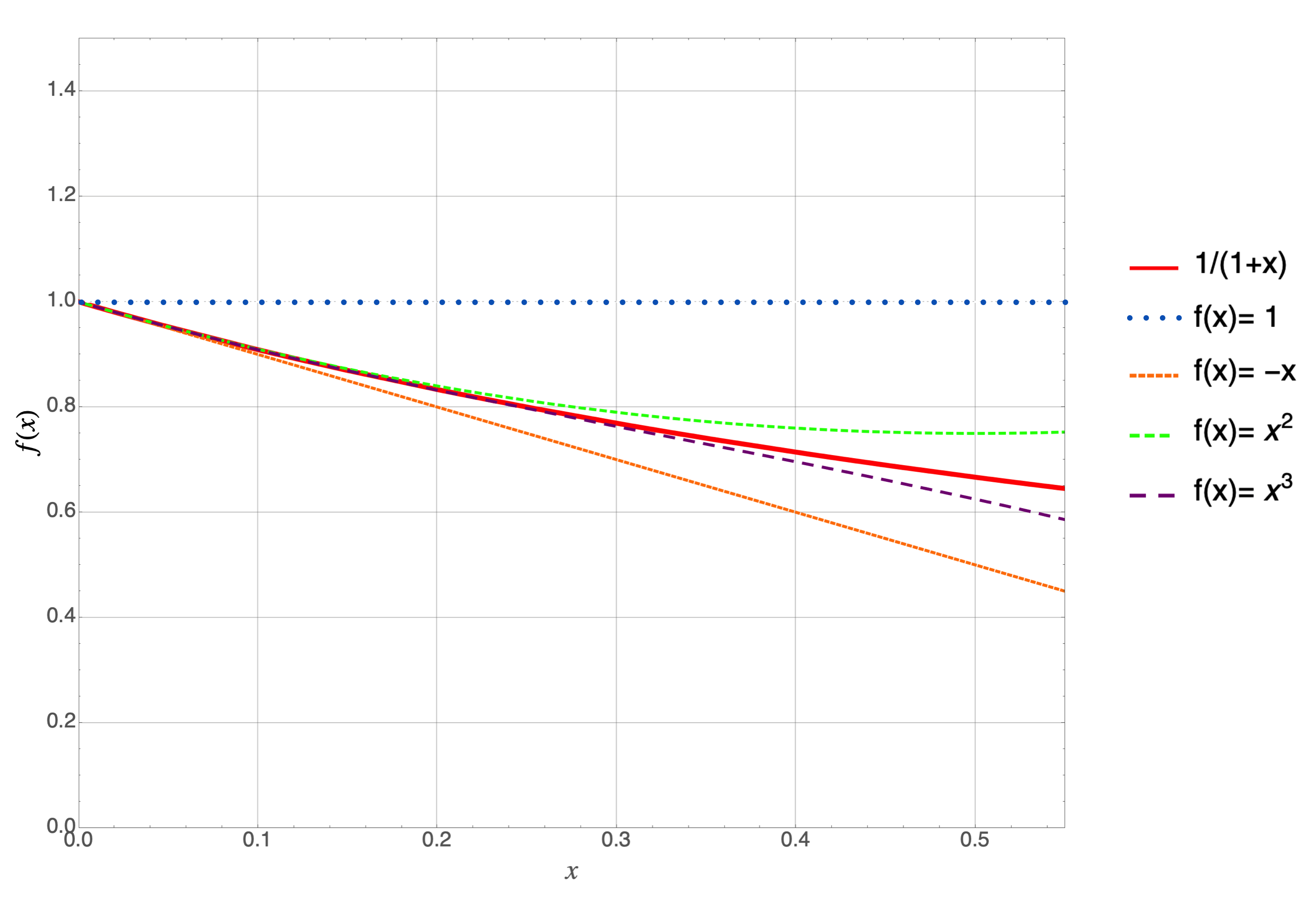

Now let’s ask our previous two questions and look for answers in the behavior of the function in this restricted graphical incarnation: when \(x\) gets very very small, the function approaches 1, just as you predicted: \(y(1>>x) \approx \frac{1}{1}.\) Likewise, when \(x\) is enormous, the function gets very small since it now looks like \(y(x>>1) \approx \frac{1}{x}.\)

But there’s a more nuanced way of looking at approximations which is due to Isaac Newton. He found a way to represent a function in pieces, for cases in which the power of such a function could be anything: a positive integer, a negative integer, or even a fraction. The pieces add together to perfectly recreate the original function. The bad news is that to do so perfectly requires an infinite number of them! The good news is that one can get very close to the original function with only a few of the pieces. In contrast to how that sounds, it’s actually very useful for many physics applications as we’ll see.

Here’s his expansion for our function:

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{1+x} \approx 1 - x + x^2 - x^3 + ... \nonumber \]

That last bit of \(...\) means that the expansion continues in that pattern for an infinite number of terms.

But notice that each term is a separate function in and of itself. That is, \(f(x)\) can be written as the sum and difference of many functions, \(1, x, x^2,...\). Add them all up and you’ll get the original function in all of its glory. Add only the first few terms and you’ll get close to the original function. Let’s do that for the first four terms and compare it to the original, full-fledged function.

Figure 4.23: The original function is in solid red and each successive curve adds the next term in the series. So, the blue dotted line is \(f(x)=1\), the first term in the series; small dashed orange is adding \(-x\), so \(f(x)=1-x\); medium dashed green is \(f(x)=1-x+x^2\); and finally, long dashed purple is \(f(x)=1-x+x^2-x^3\).

Let’s zoom into the region in the box.

(#fig:combinedfunction_blowup)CAPTION

Wait. I’ve had more fun than this…

Glad you asked. Here’s the punchline. You’ll thank me when we get to relativity. Or not.

Suppose that all you cared about was \(x\)’s that are less than about 0.1 and you need to evaluate the curve quickly, or gain some physics insight for that small of an \(x\) region. Then you could get away with approximating

\[\frac{1}{1+x} \approx 1-x\]

Look at how close the solid red curve is to the short dashed orange curve. Good enough.

Suppose you cared about \(x\)’s that are less than 0.3…then \(1-x\) would not be accurate enough, but the long dashed purple curve would be since it’s indistinguishable from the solid red curve up to that point.

Look how each curve successively makes the approximation better and better as \(x\) increases. So if you can be confident that your \(x\)’s are going to be less than say 0.1, then you can approximate the original function with maybe the first two terms:

\[f(x) \approx 1-x \nonumber \]

since the blue and orange curves when added together are neatly underneath the red curve. The more terms we might add the further out in \(x\) that agreement would continue. Add an infinite number of terms—not advisable—and you’d perfectly reproduce the original function.

Remember this! It will become important later when we’ll encounter some physics functions and approximate them with a few terms of the expansions that we’ll encounter. Here are the functions that we’ll see in the lessons ahead:

\[\begin{align} \sqrt{1+x} &= 1+ \tfrac{1}{2} x - \tfrac{1}{8}x^2 + \tfrac{1}{16}x^3 - ... \\ \frac{1}{ \sqrt{1-x}} &= 1 - \tfrac{1}{2} x +\tfrac{3}{8}x^2 - \tfrac{5}{16}x^3 + ...\label{approxgamma} \\ \frac{1}{ 1-x} &= 1 + x + x^2 + x^3 + ... \\ \frac{1}{ (1+x)^2} &= 1 - 2x + 3x^2 -4 x^3 + ... \label{approxforce} \end{align}\]

Thanks, Isaac.

4.8.5 Formulas From Your Past That Might Only Be Referenced Informally

Ellipses and hyperbolas will come up, but descriptively. I’ll just want you to have a feel for their shapes and some of the terms that are defined by them. Just file away this location and we’ll come back only a few times.

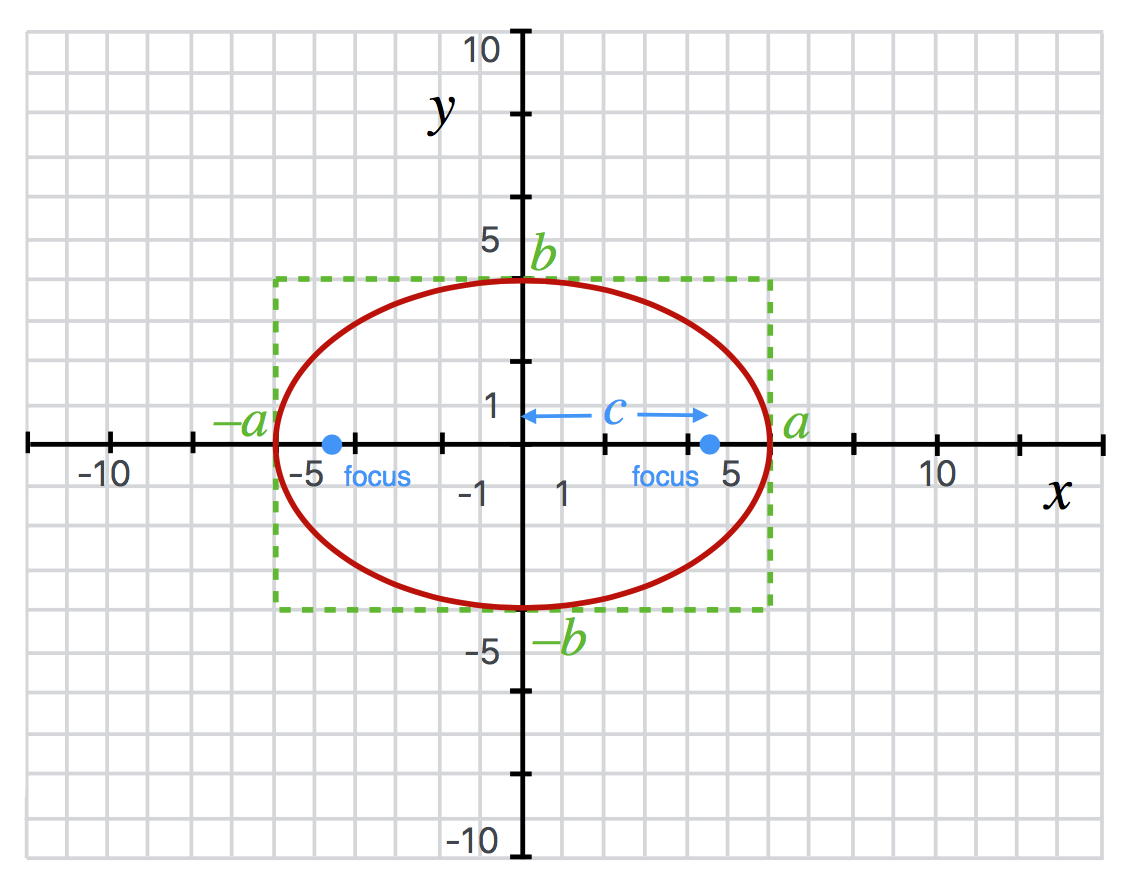

4.8.5.1 Equation of an ellipse

An ellipse is a squashed circle (?) that has two axes, the major axis (\(a\)) and the minor axis (\(b\)). The points at which the curve goes through the axes at the major axis points are called the vertices of the ellipse. The equation of an ellipse centered on the origin is

\[\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{b^2}=1.\]

The figure of an ellipse centered on the origin is here:

Figure 4.24: An ellipse with equation \(\frac{x^2}{36}+\frac{y^2}{16}=1.\)

The focus (\(c\) in the diagram) of an ellipse is shown and has the relationship to the curve in that any line connecting one focus to the curve and then to the other focus is always constant. The relationship to the major and minor axes is \(c^2 = a^2-b^2.\) So, if \(a=b\) then the ellipse is actually a circle and the position of the focus is at the center of the circle, here the origin. The degree to which an ellipse is almost-circle-like (more symmetric) and almost-flattened-like is determined by its “eccentricity,” \(e\). It’s defined as \(e = \frac{c}{a}\). So an eccentricity of zero is a circle and the larger the eccentricity, the more the focus point is close to the vertex…and the flatter it is.

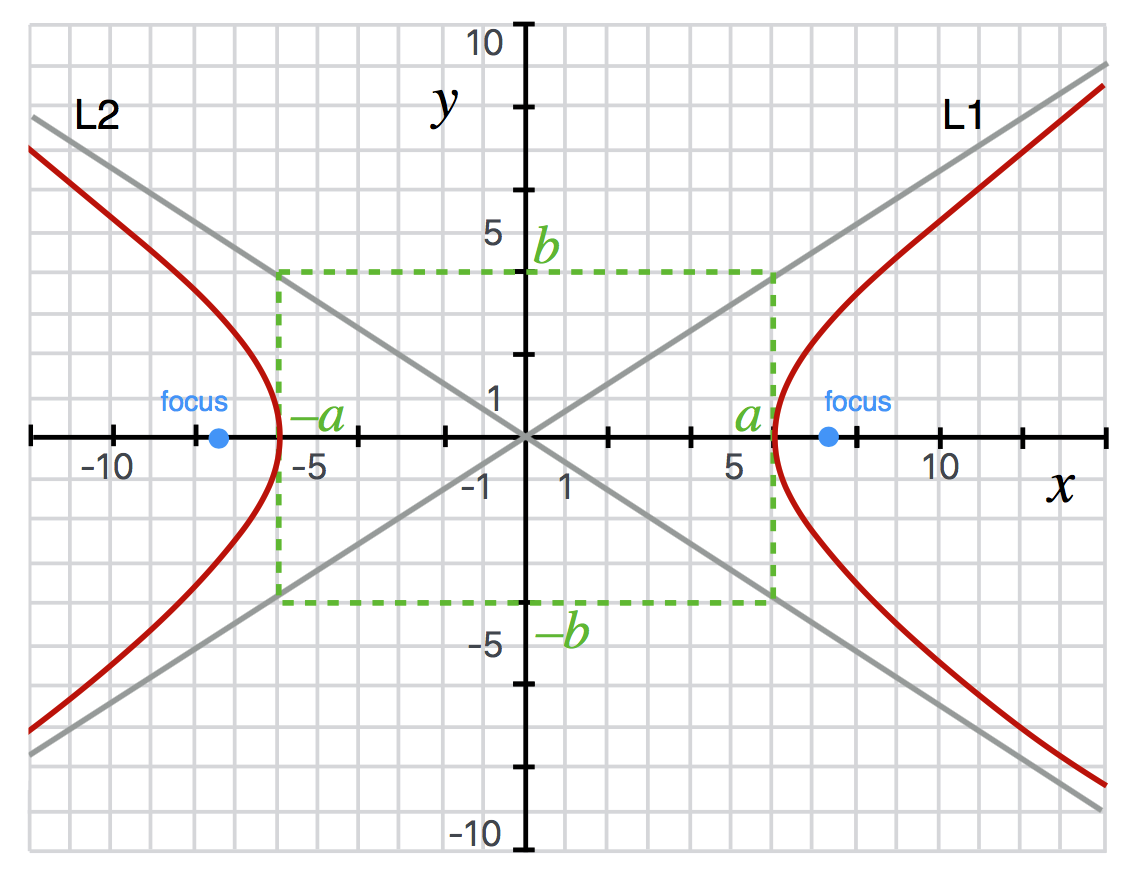

4.8.5.2 Equation of a hyperbola

I’ll want to refer to a hyperbola once in QS&BB and it will have a particular shape. This particular form of hyperbola is open to the right and left and crosses the \(x\) axis at \(\pm a\)—the “semi-major axis”—and has a semi-minor axis of \(b\) (see the figure). The equation is

\[\frac{(x-x_0)^2}{a^2} - \frac{(y-y_0)^2}{b^2} = 1.\]

The points \((x_0, y_0)\) are where the center of the hyperbola is and in the figure, that’s the origin.

There are a variety of definitions which you can see on the diagram.

Figure 4.25: The equation of this hyperbola is \(\frac{x^2}{36} - \frac{y^2}{16} = 1.\)

4.9 What to Remember from Lesson 3?

This has been a whirlwind pass through lots of mathematics from you past. I’d like you to remember that functions are nothing more than little machines for taking a variable and turning it into a value. The world seems to be astonishingly well described by models made up of functions! Some of them are easy and some of them are complex. Only some very simple manipulations will be required. See the Fairness Doctrine of Algebra!

I’ll ask you to “read” functions sometimes, but I promise: only when they are simple and only when there’s physics insight to be gained from that. Otherwise, we’ll be content to read graphs to “evaluate” functions because, well, it’s the same thing.

4.9.1 Powers of 10.

That will be an important tool since we’re talking about the largest things in the universe and also the smallest things in the universe.

4.9.2 Geometry

There are some simple equations, areas, and circumferences of geometrical objects that I’ll need you to remember: line, circle, triangle.

4.9.3 The rest

The rest of the items in Lesson 3 are there for you to refer to when we touch on some science stories that need them.

Marishal College was merged with another university and Maxwell was deemed “redundant” because there is only one “professor” in any subject.↩

Remember, he insisted that all Earthy matter would head for the center of the Universe, which was the center of Earth. So from all directions, the built-up mass that is our terra firma, would create a sphere. Also it was well-known that the Moon shines because of the Sun’s light and the phases of the Moon were a reflection of the Earth’s shadow across its face. So nobody of Greek influence believed that the Earth was flat.↩