12.3. Induction#

By 1831, he managed to clear his research decks sufficiently to take on a problem that had plagued him, as well as others. Clearly there were two ways to produce electricity: one could use friction—the silk and fur rubbed on glass and amber (your socks on the carpet) or use chemistry – a battery. And, Oersted and Ampère had shown that electricity – in the form of a current – could produce magnetism. So surely magnetism should be able to produce electricity?

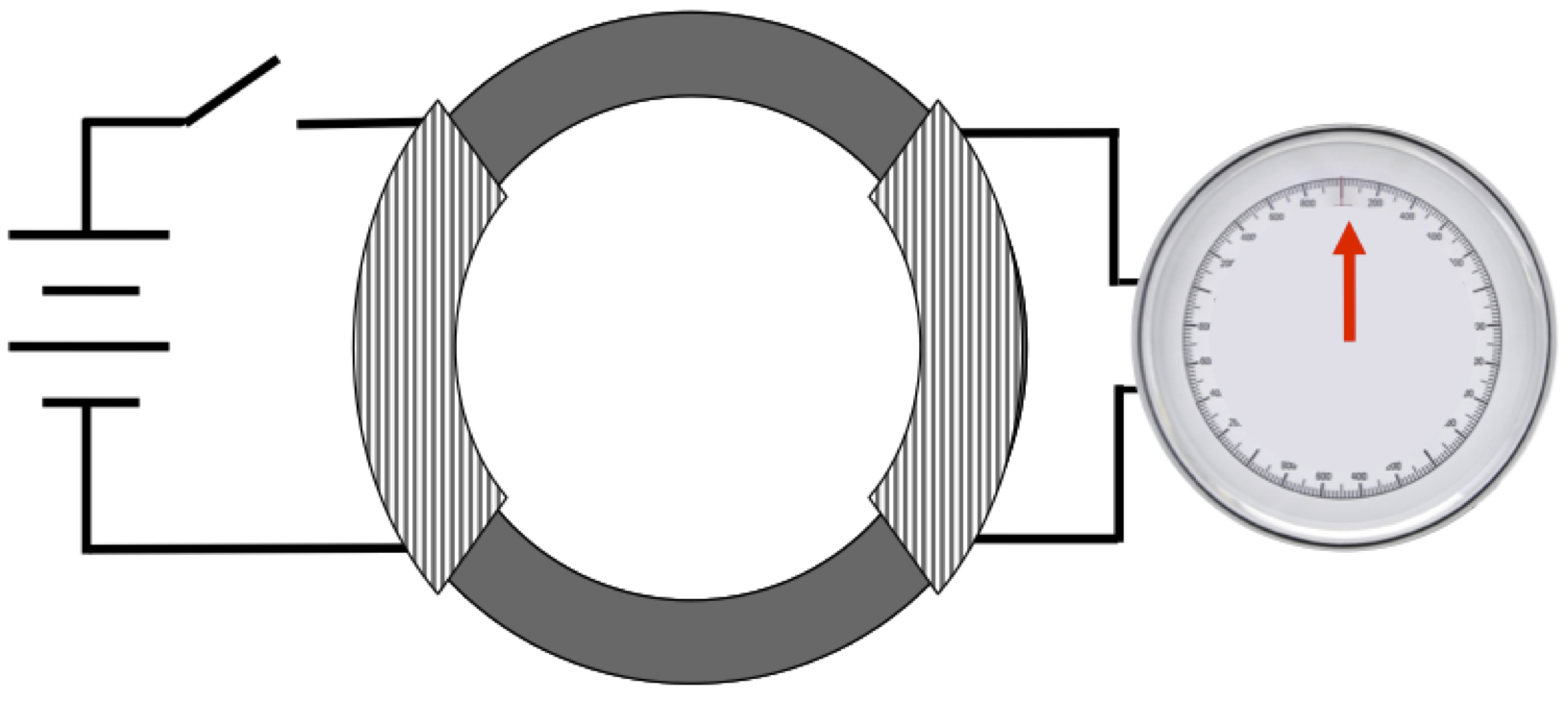

Faraday went into a furious series of experiments trying all manner of materials and conductors which mostly consisted of trying to take adjacent circuits and get one to cause a current in another. His inspiration came when he took two long wires and wrapped them individually in paper and then wove them together around a core of a circular iron ring. One of his cores is shown at the right.

The paper insulated the wires from touching, but they were all very close to one another. He hooked one set to a battery and looped the other circuit over a sensitive magnetic needle as shown in the figure below. If the needle moved when the current flowed in the first circuit, then it would have been induced by the interwound, but insulated wires. Multiple tries didn’t succeed until he noticed that the needle moved when the circuit was closed and then when it opened…and was stationary when the current just flowed. That was the key which everyone had missed, including after seven years of effort by Faraday: currents don’t induce magnetism, but changing currents do!

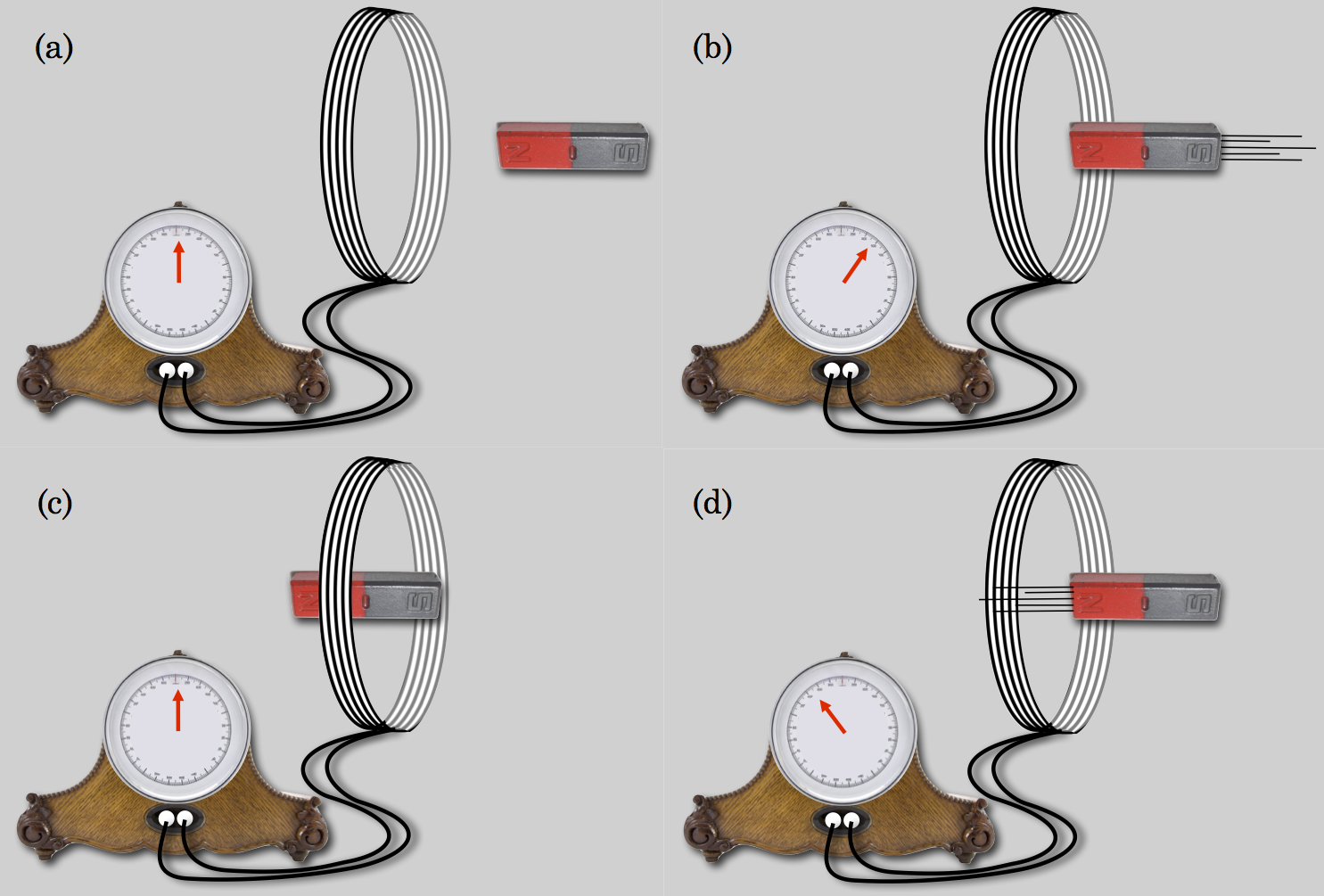

Subsequently, he found another demonstration of a similar sort, but more directly and forcefully a magnet inducing electricity. In the figure below is just a loop of wire connected to a Galvanometer. No battery. No currents. Pointed at the loop is a bar magnet. That’s it. Hold the magnet still, nothing happens. But, move the magnet toward or away from the loop and a current flows in it! Here, the changing magnetic influence is caused by a mechanical motion of the magnet. Current is created by a changing magnet, which is the principle behind a Generator. Keep this little experiment in mind.

The ability for current to flow seems to be inside of the wire and by changing a magnetic field in the vicinity of the wire, that current is induced to flow. This phenomenon is called Electrical Induction and it’s the principle behind all generators—creating current out of magnetic motion—and motors, its inverse—creating motion out of currents.

A _changing_ magnetic influence creates a current.

What’s responsible for all of these various phenomena? Faraday had the standard repugnance for Action at a Distance, and knew that that wasn’t an explanation of anything anyway. He wasn’t so bound to the idea as were his classically trained colleagues, and so he thought about it in his own, fresh mind.

Faraday announced his discovery to the world at a meeting of the British Royal Society on November 24, 1831. That led to a priority struggle, as the publication of the effect was in early 1832, by which time the effect had been repeated in France and Italy…and where popular press reported that Faraday had confirmed the effect, rather than discovered it. He never again announced a discovery before formally publishing it in an international journal. The French and Italian scientists all acknowledged his priority and so trouble was averted. By now “Professor” Faraday – the uneducated printers apprentice – was world-renown and what he said and did mattered.

Please answer Question 4 for points:

Please answer Question 5 for points:

Missing In Action

Faraday handled mercury and other dangerous materials as a matter of course. In his middle age he suffered a serious lack of memory and bouts of dizziness that took him out of action from about 1839 until 1845. It must have been terrifying. He was forced into months of seclusion and was absent from research only giving a few public lectures in the 1840s. Speculation is that he had poisoned himself. Can you imagine someone as energetic and inspired as Faraday, unable to work? Neither could Sarah, who enforced strict social access to her husband throughout his convalescence. He eventually recovered and resumed his activities. The challenge that seemed to energize him was his evolving view of space and the vacuum.