15.5. Getting Serious: The Michelson-Morley Experiment#

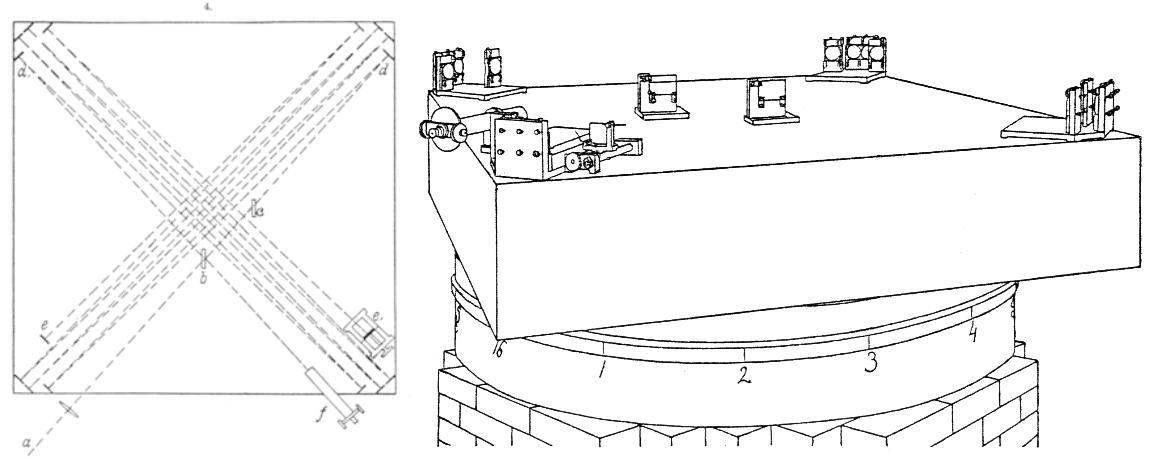

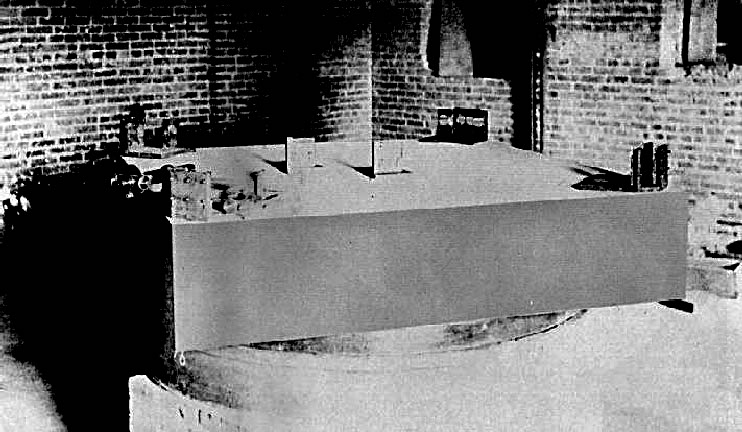

When Michelson’s time in Germany (and Paris) was done, the future was uncertain and so he was delighted to discover that colleagues had interceded on his behalf to offer him a faculty position at the brand new Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland, Ohio. (This is now the very fine Case Western Reserve University.) With sufficient startup funds and laboratory space, Michelson readily accepted the position, resigned from the Navy, and in 1881 re-established his light-speed measurement work in Cleveland. There he teamed with Case chemistry professor Edward Morley (1838-1923) to do it better. MM_Case shows an engineering drawing of the apparatus that they constructed.

Outside vibrations had been a problem in Berlin and while reduced in Potsdam, they were still a problem. What they did was build the new apparatus on a huge, heavy sandstone slab that floated in a pool of mercury–a dangerous environment. This isolated it vibrationally and allowed the experimenters to keep the whole instrument in constant rotation, slowly, so that the directions of the arms are constantly, uniformly changing. That would eliminate any potential bias. Furthermore with high quality mirrors the light paths were essentially increased back and forth to 36 meters in effective length which greatly improved the precision.

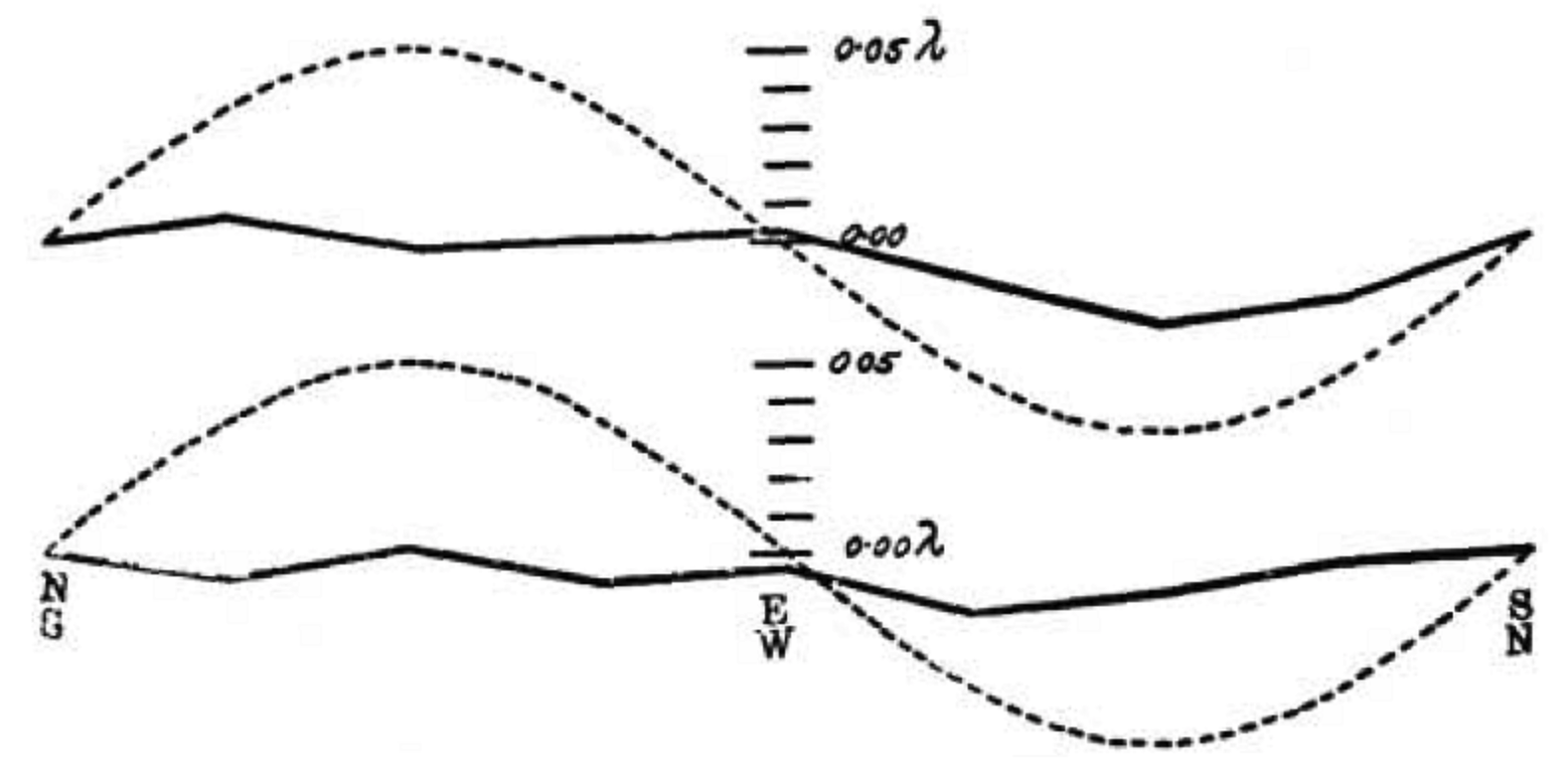

So on six days in July they did their experiment walking around the circle looking into the eyepiece all the while in 30 minute shifts each. Here are their results:

In August, 1887, Michelson wrote to John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh – future Nobel Laureate and another king of physics:

The Experiments on relative motion of earth and ether have been completed and the result is decidedly negative. The expected deviation of the interference fringes from the zero should have been 0.40 of a fringe — the maximum displacement was 0.02 and the average much less than 0.01 — and then not in the right place.

As displacement is proportional to squares of the relative velocities it follows that if the ether does slip past [the earth] the relative velocity is less than one sixth of the earth’s velocity.

The result is unequivocally zero. For Michelson it was a failure. Either the ether moves with the Earth or there is no ether. Or something else, like Lorentz’s hypothesis. Neither Michelson nor anyone could imagine that the ether didn’t exist.