5.3. Getting From Here to There: At Constant Speed#

Motion is both the easiest and the hardest concept in physics and so much of what comes for us will constantly stretch at ideas about what motion is and how we can describe it. So we need to start at the beginning.

You’ve been dropping things since you were a toddler and you learned the hard way that if you drop something from a high place it will more likely break than from a low height. You learned that the harder you throw a ball, the faster it will leave your hand, the more damage it can do to a window, and the farther it will go before landing—and that it always comes down.

If time doesn’t march on, we’ve not moved. But what is time? “Tubby…paused. ‘Time,’ he added slowly – ‘time is what keeps everything from happening at once…” [1] We’ll see time take on a new meaning.

The final frontier, Space, is either “just there” or it’s a relationship among extended objects. If all of the things in the universe disappeared, is there space left over? That’s an old, contentious issue and maybe was finally solved by Einstein.

What’s the difference between space and time? In “speed” they are just two sides of the same coin, or two sides of the same ratio. But don’t you usually think of them as different things? One’s not more important than the other is it? Eventually, we’ll let Einstein chime in here.

Particular speeds seem to be important. Mr. Galileo taught us about one and James Clerk Maxwell and Albert Einstein taught us about another. (There he is again.)

From that simple word-equation, so sensible and so obvious, I’ve hinted at at least five complications. We have learned to ask simple questions and discover that they sometimes lead to important and surprising directions.

motion: it’s everywhere

Almost everything in physics boils down to: motion. (Even boiling.)

Whether it’s runners on a track, the cosmic rays piercing us all the time, orbiting planets, electrons in a wire, electromagnetic waves, quark wavefunctions inside a proton, electrons and holes in a semiconductor, or the stretching of spacetime itself. Everything is about “motion.”

These first lessons on the physics of my grandparents’ generation will establish the language and tools that we’ll need in order to pursue the more exotic forms of motion and we’ll become skilled at manipulating concepts (and their attendant symbols) like velocity, kinetic energy, mass, momentum, and force. Each of these terms has a sixteenth to nineteenth century origin, but each has managed to keep up with the times as layer upon layer of subtlety is discovered about each of them as we dig deeper and discover more.

But at its most basic, our physics will be all about how to get from here to there and from then to now, and to be able to explain how that happened and predict what will come next.

5.3.1. Speed in Modern Terms#

Let’s make this more compact by inserting customary symbols to get rid of the English words. Here are some grammar rules in QS&BB:

We’ll limit ourselves almost exclusively to motion in one dimension in space.

We’ll use the symbol \(v\) for speed (because customarily, we’ll speak of “velocity”…more about this below).

We’ll use the symbol \(x\) for distance in one dimension, regardless of which direction it points.

We’ll use the symbol \(t\) for time and almost always presume that we set our clocks so that the beginning time of any interval is \(t_0=0\).

Oh, and we’ll use the subscript \(\text{ }_{0}\) to indicate the beginning of some time or location interval—” \(t_0\)” or ” \(x_0\) ”—in a sequence of events.

We’ll use the Greek symbol Delta, \(\Delta\) to mean “change of”…this will come up a lot.

See. You already know a lot about motion. Let’s go “up north.”

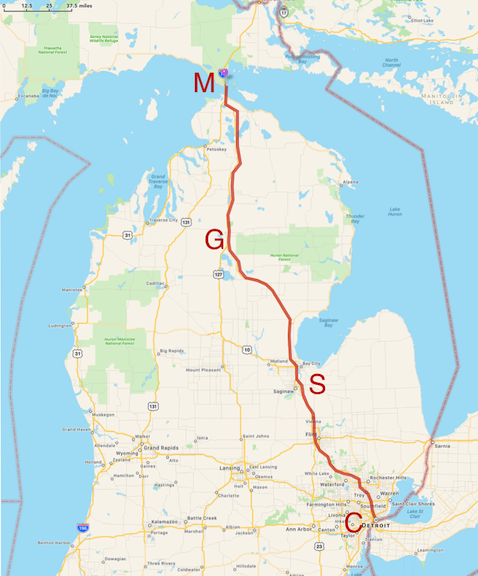

You see the various towns along the way and in this trip we’ll be abstract in a couple of ways. That curvy line following the actual roads we’ll pretend is just straight so we could define a coordate system with \(x\) following the SE to NW path and in which \(x=0\) is at Comerica Park. The second way we could abstract this scenario is to imagine that we’re so good at the controls that we can drive at a constant 60 mph the whole way—no stopping, no slowing down or speeding up.

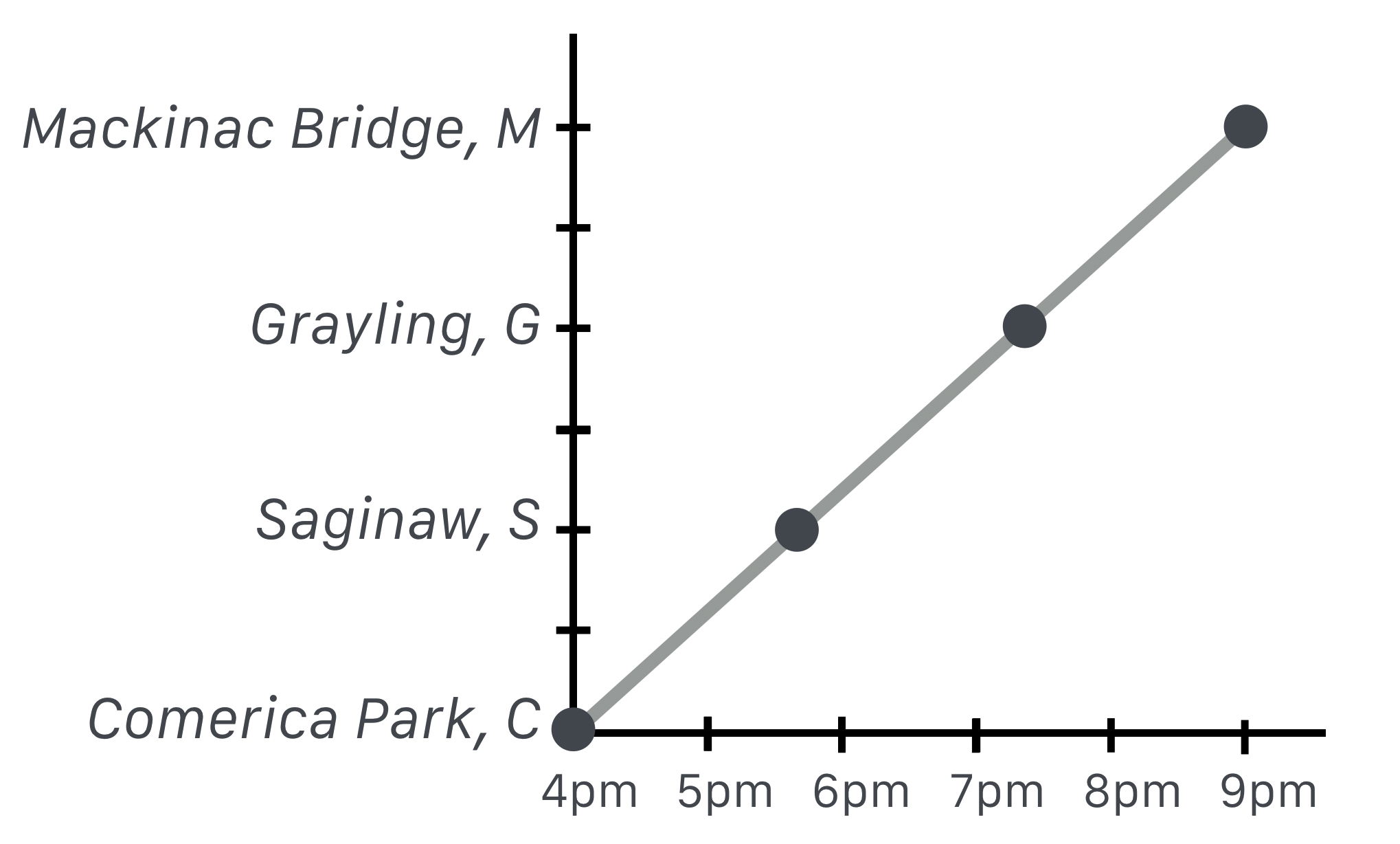

If our copilot got our her watch and wrote down the time that we breezed through Saginaw, Grayling, and when we got to the bridge she could create a graph which would look like this.

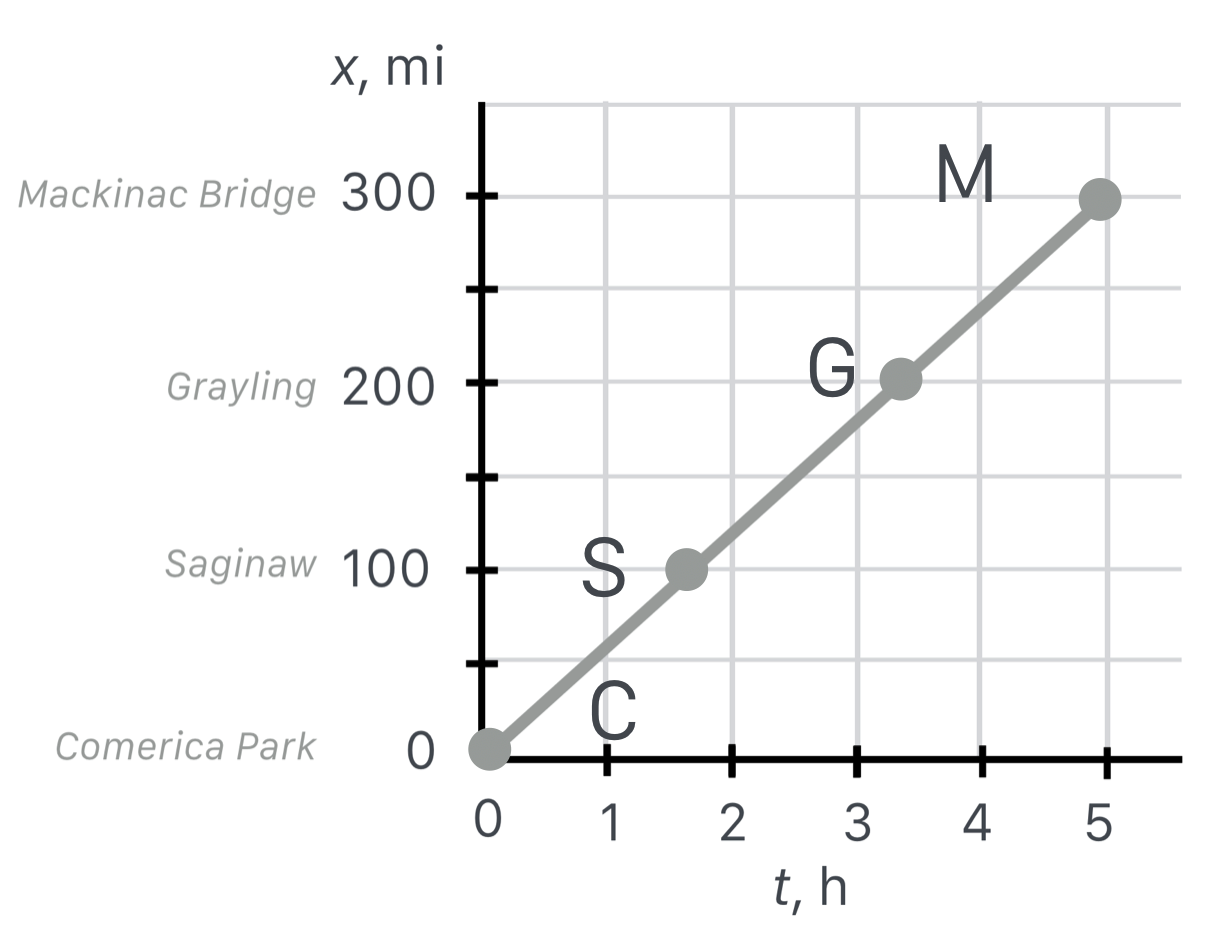

It’s a lot easier to use numbers rather than names and clock times so let’s replace the names of the towns with their distances from the beginning and use decimal hours on the horizontal axis starting at the 4 o’clock point which we have the freedom to define to be \(t_0 = 0\).

That straight line in the distance plot is a familiar thing and we’ll model that in Lesson 5. But there’s a lot there. If we carefully made this plot before we left, then if asked, we could say how long it will take us to get to Grayling.

Question! So, how long will it take to get to Grayling at a constant 60 mph?

Glad you asked. I just follow the \(y\) axis to the right from the 200 mi point until I hit the line and then read down from there and get: about three and a quarter hours.

Good job!

Question! The fact that the line of distance versus time is straight means what?

Glad you asked. No matter where we are on the graph (on the road!), the rate at which distance increases is the same anywhere along the way. From the park to Saginaw, it’s \(100\) miles/about \(1.7\) hours which is about \(59~\)mph. From Saginaw to Grayling is \((200-100)/(3.3-1.7) = 100/1.6 = 63~\)mph. The whole trip is \(300/5=60~\) mph. I get the same thing everywhere.

So the straight line of distance versus time for a trip means that the speed is constnat.

Good job!

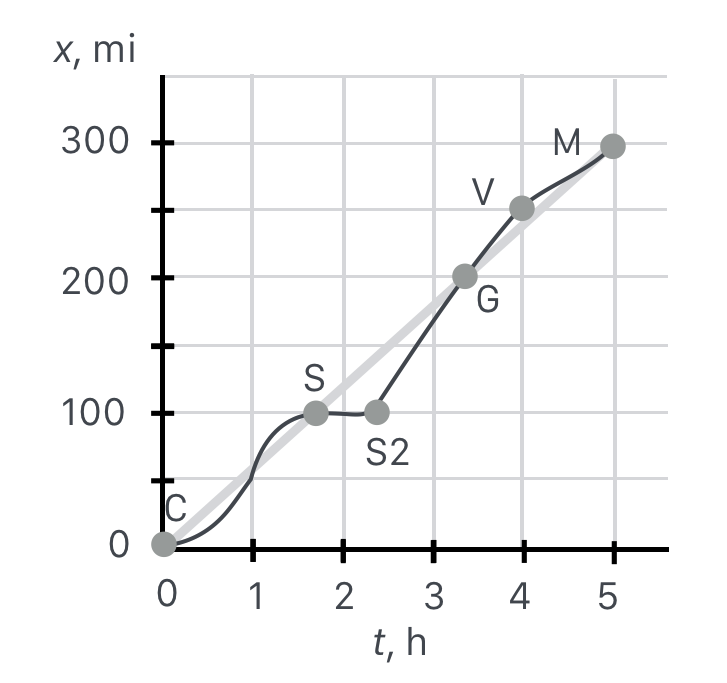

Now I don’t know about you, but I can’t drive precisely at 60 mph for 10 minutes, let alone for 5 hours. So here’s a more realistic image of what the distance versus time relation might be.

Here the dark line is meant to represent a more realistic journey with the light gray line showing the originally ideal, constant velocity trip. Notice that we start slow and speed up and then at Saginaw we stop for dinner: the distance is unchanged for almost an hour until point S2 when we start up again. And boy, do we ever. We fly through Grayling G) on to Vanderbilt (V) and then more slowly, get to the bridge.