7.1. A Little Bit of Huygens#

Isaac Newton wasn’t the only smart guy around. He had respect for only a couple of contemporaries and Christiaan Huygens, a Dutch gentleman of means—and oh, by the way, a genius astronomer, inventor, and mathematician of such esteem that he was a elected foreign member of the British Royal Society—was one of them. Another was his rival for the invention of calculus, Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz. It’s interesting that neither of these two had academic day jobs. Huygens did what he pleased and Leibniz was a diplomat for the House of Hanover for much of his life.

Christiaan Huygens grew up in a privileged household in the Hague where his father, Constantijn Huygens, was a diplomat and an advisor to two princes of Orange. The Huygens’ home was unusual. Guests included Descartes and Rembrandt, whom Constantijn helped support. Constantijn was also a correspondence friend of Galileo, a poet and musician, and was even knighted in both Britain and France. So perhaps it was logical that he would provide for Christiaan’s home-schooling.

Fig. 7.1 Christiaan Huygens, 1629-1695#

When ready, Christiaan was sent to Leiden University to study law two years after Newton was born, whereupon he discovered professional mathematics. A pattern we’ve seen before, although unlike Galileo’s case, Christiaan’s mathematical education had included encouragement from Descartes when he as a child. So his father was much more understanding…and the need for a “job” was never an issue in this family.

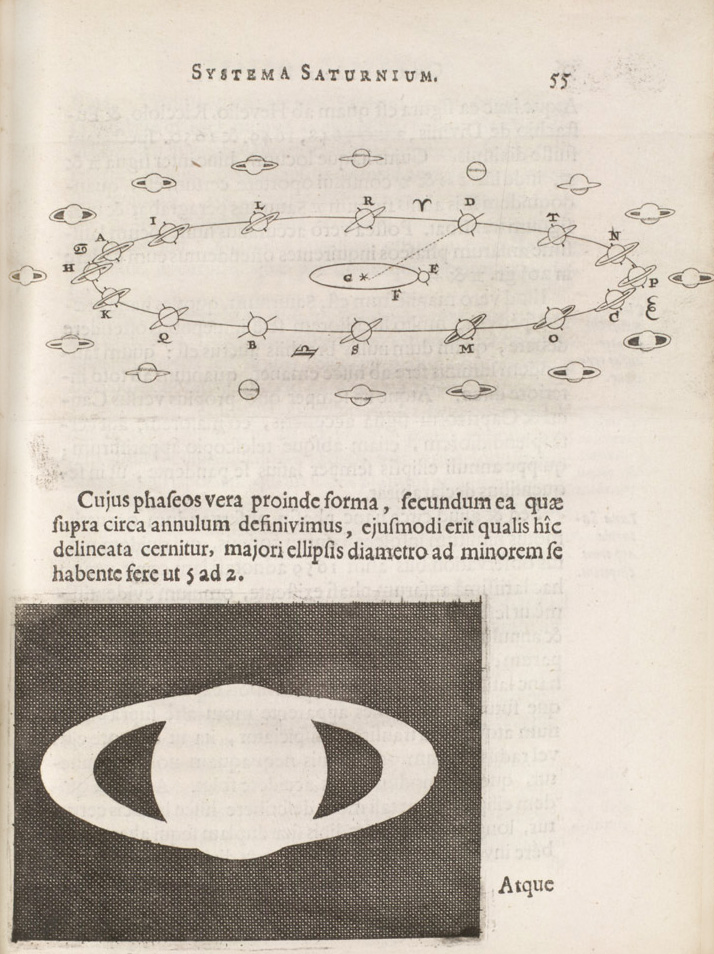

Huygens became interested in astronomy and learned to grind and polish lenses in a new way which led to the development of a telescope of unparalleled quality. Among his first discoveries was the large moon of Saturn, named Titan and then the resolution of Saturn’s rings.

Fig. 7.2 From Huygen’s Systema Saturna: Galileo’s telescope could only vaguely see that there was some unnatural bulge in Saturn’s shape. Huygens’ higher quality mirrors were able to resolve that side-bump into the rings.#

The space probe “Huygens” was designed by the European Space Agency and landed on Titan on January 14, 2005. The arc from Christiaan Huygens’ first glimpse of Titan to the modern photograph of its surface is a nice story.

Fig. 7.3 The surface of Saturn’s moon, Titan as captured by the ESA space probe, Huygens.#

An increasingly precise program of astronomical observations led him to the need for more accurate time-keeping, whereupon he invented the first pendulum clock (think “Grandfather”)—by fashioning a pivot that made the pendulum swing in the pattern of a cycloid, rather than strictly circular motion of an unhindered pendulum. Galileo had shown that the period of a pendulum was independent of the amplitude of the swing (“isochronous”) but this is only the case when the amplitude is small. Huygens showed mathematically and then by construction that if the bob can be made to take the path of a cycloid, that the motion would be isochronous even for large swings, and hence useful in a clock. He also carefully considered the forces on an object in circular motion and the derivation of the centripetal force in the last lesson was actually obtained first by Huygens for a circle.

However, he was confused by the tendency of an object to move away from the center of a circle and called the force out “centrifugal force.” Newton also was initially confused by this but figured out that gravity, for example would pull in and hence coined the name “centripetal” to contrast it to Huygen’s idea. Newton’s analysis was general and included circular, elliptical, parabolic, and hyperbolic orbits, so we tend to credit him with the correct understanding of curved motion.

Huygens traveled widely and spent considerable time in Paris in multiple long stays. He visited Britain many times as well, and when he thought he was dying (he was often in frail health) he bequeathed his notes to the British Royal Society. (He recovered.) His scientific circles were very broad and he counted as among his friends most of the intellectuals of the day, including Boyle, Hooke, Pascal, and indeed, Newton whom he visited shortly after Principia was published. Christiaan Huygens died at the age of 66 four years after his visit with Isaac Newton, who referred to him as one of the three “great geometers of our time.”

For our current purposes, it was Huygens’ consideration of collisions that is his legacy. Descartes had considered the problem of colliding two objects together and he applied his notion that all motion in the universe is conserved to such problems. But he was confused about just what was conserved and didn’t have an appreciation of vectors or momentum. Putting Huygens’ work together with Newton’s gives us our modern ideas about how the total momentum of a system of colliding objects is preserved and that’s our concern in this lesson.

In particle physics we’re all about collisions and we construct huge, international facilities to do nothing but crash things together. Yet we still use the same ideas and language first invented in the 17th and 18th centuries, albeit fancied up for modern applications.