9.1. A Little Bit of Kepler#

Fig. 9.1 Johannes Kepler, 1571-1630. The treasures hidden in the heavens are so rich that the human mind shall never be lacking in fresh nourishment.#

One of the most interesting and courageous scientists of the 17th, or maybe any century, was the German Johannes Kepler (1571 - 1630). His personal life consisted of one disaster and tragedy after another. His professional relationships ranged from tempestuous to subservient. His first non-royal employer, Tycho Brahe, was a tyrant and upon his death, Kepler “liberated” Tycho’s extensive observational data on the orbit of Mars and fought the Brahe family in and out of court for years. His relationship with Galileo was adolescent: Kepler always cheerful nearly begging for notice from the then famous Italian. Galileo basically ignored him unless he wanted something.

Kepler was continuously sick, perpetually destitute, a magnet for personal tragedy, formed by an awful childhood, lived in terrible environments, and was aggressively self-loathing.

“That man has in every way a dog-like nature. his appearance is that of a little lap-dog. Even his appetites were like a dog; he liked gnawing on bones and dry crusts of bread, and was so greedy that whatever he saw he grabbed; yet like a dog he drinks little and is content with the simplest food…He is bored with conversations, but happily greets visitors like a dog; but when something is snatched from him, he sits up and growls. He barks at wrong-doers. He is malicious and bites people with sarcasms…He has a dog-like horror of baths…” Self-description at 25 years of age.

The single common feature of Kepler’s adult life was the terrible Thirty Year’s War which killed as much as a third of the German population. Whole towns would switch allegiance to Catholicism or Protestantism overnight depending on which army had passed through last. Kepler as a Protestant, was sometimes tolerated and sometimes evicted.

He was incredibly prolific, writing many books on astronomy, mathematics, and optics. He wrote one of the first science fiction novels, a third-person autobiography and left volumes of correspondence with intellectuals and political leaders from all over Europe.

He was educated to be a Lutheran minister, but stumbled into astronomy and mathematics and learned Copernicanism outside of classes with one of the early supporters. He graduated but because of prodigious mathematics skills he became an atrocious math teacher at the Protestant school in Graz.

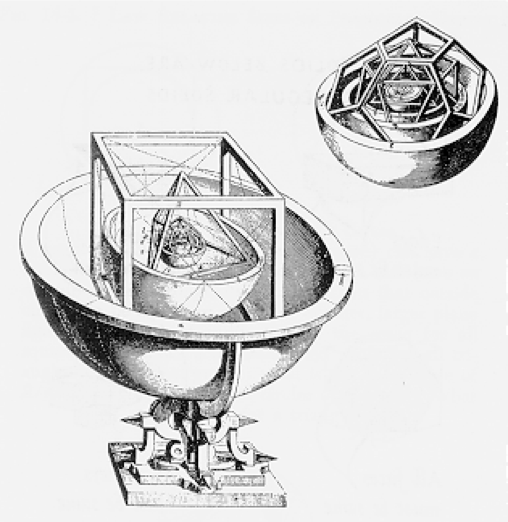

Fig. 9.2 From Mysterium Cosmographicum showing how the different geometrical solids nest together with the orbits surrounding their inside and outside dimensions. Kepler commissioned a jeweler to make a solid model of the whole contraption.#

He was plagued by many questions in astronomy: Why are there six planets? Why do the speeds of the planets decrease the further away from Earth? Why are they ordered in the way they are? He was obsessively detailed in his scientific writings and so we know that on July 9, 1595, while he was boring himself to death in his own lecture, he had a sudden realization. He thought he’d come on a beautiful description of the planets’ spacing. There are five so-called Platonic solids—all others can be broken down into combinations of the five: cube, dodecahedron, icosahedron, octahedron, and tetrahedron. What he found—he thought—was that if one imagined a sphere on the outside of each of the centered, increasingly bigger, and nested shapes in the order, octahedron, icosahedron, dodecahedron, tetrahedron, and cube…that the radii of those spheres correspond to the relative radii of the planets. Numerically, it was close. The figure above is the famous rendering that he inserted by hand in his eccentric 1596 book, Mysterium Cosmographicum (The Cosmographic Mystery). It’s madness of course. But in a nice way. Kepler’s writing style was unusual, essentially a narrative, describing his highs and his lows. His passionate enthusiasm was naive-sounding, but it was who he was.

“It is amazing! …although I had as yet no clear idea of the order in which the perfect solids had to be arranged, I nevertheless succeeded…in arranging them so happily… Now I no longer regretted the lost time. I no longer tired of my work; I shied from no computation, however difficult…day and night I spent with the calculations to see whether the proposition that I had formulated tallied with the Copernician orbits or whether my joy would be carried away by the winds…within a few days everything fell into its place. I saw one symmetrical solid after the other fit in so precisely between the appropriate orbits, that if a peasant were to ask you on what kind of hook the heavens are fastened so that they don’t fall down, it will be easy for thee to answer him.” Farewell! (Kepler, Mysterium Cosmographicum)

Not your standard scientific writing.

While this work was mostly fanciful at best, it set the stage for a number of similarly manic publications in understanding the motions of the planets that rhetorically meander their way to world-changing conclusions. He started working out the questions that needed to be asked.

“If we want to get closer to the truth and establish some correspondence … between the distances and velocities of the planets then we must choose between these two assumptions: either the souls which move the planets are the less active the farther out the planet is removed from the sun, or there exists only one moving soul in the center of all of the orbits, that is the sun, which drives the planet the more vigorously the closer the planet is…”

It’s not a spoiler to note that the idea of a force from the Sun in Newton’s hands led to our classical idea of gravity. Kepler was the first to imagine such a thing, a generation before Newton.

Wait. Doesn’t this sound like Gravity as we’ve all learned it?

Glad you asked. Yes, and that’s one of the neat things about Kepler: he was imaginative and ahead of his time in many ways. He envisioned that the Sun pulled on the planets with what he called a “Soul” but he also imagined that there needed to be a force pushing the planets around their orbit, and there he was mistaken.

The year after Mysterium, he married a rich, twice-widowed woman and began a family. Within two years their first two children perished, Graz was overthrown, and he and his family had to leave. It was in 1600 when he and Tycho Brahe’s paths crossed. By this time Tycho had been evicted from his island laboratory and moved his entire circus to Prague. As we’ll see later, Tycho hired Kepler and assigned him the “problem of Mars.” Kepler predicted that he’d work out the details of Mars’ orbit in 8 days and he succeeded, but 10 years later. This he did, by basically stealing the data in the immediate aftermath of Tycho’s death.

“I confess that when Tycho died, I quickly took advantage of the…lack of circumspection…of the heirs, by taking the observations under my care…”

Kepler got Tycho’s old job in 1601 as the Imperial Mathematician to the Holy Roman Emperor, His Highness, Rudolf II…who was quite unstable. He spent the rest of his life trying to actually collect his salary, which became years in arrears.

Fig. 9.3 A NEW ASTRONOMY Based on Causation or a PHYSICS OF THE SKY derived from Investigations of the MOTIONS OF THE STAR MARS Founded on the Observations of THE NOBLE TYCHO BRAHE.#

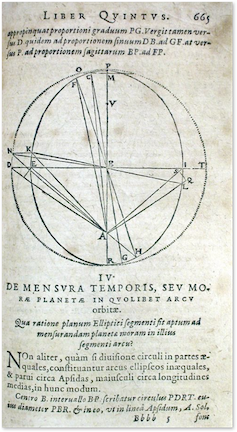

Analytic geometry had not been invented when Kepler began working on the Mars orbit, so he relied on geometry, spherical trigonometry, and the newly invented logarithms, which can be used to simplify multiplication and division of large numbers (a slide rule is based on logarithms). Think about what he had to do. Tycho had thousands of individual position measurements of where Mars appeared as measured from Earth. We know that both the Earth and Mars are moving relative to the sun. Kepler’s research program—as a good Copernican—was to translate those data fro an Earth vantage point into Mars’ trajectory as viewed from the Sun. That’s a really hard calculation! It took him six years of heroic calculations. He struggled with circles—which didn’t work—then with an oval (!)—and then finally realized that the trajectory was an ellipse. He finally admits, in his Kepler-kind of way in Chapter 60 of his 1609 book, Astronomia Nova (New Astronomy):

“Why should I mince my words? The truth of Nature, which I had rejected and chased away, returned by stealth through the backdoor…I thought and searched…as to why the planet preferred an elliptical orbit…Ah, what a foolish bird I have been.”

This is one of the most important books in the history of astronomy. In it he enunciates two of “Kepler’s Laws,” which we’ll talk about below. But he also—for the first time in 2,000 years of recorded history—asserts that planets do not move in (the perfect) circles that everyone believed was absolutely required of the cosmos. Think about how intellectually courageous this was, just a few years before Galileo was severely punished for an even more revolutionary opinion than this.

Fig. 9.4 From Astronomia Nova showing one of Kepler’s diagrams comparing an ellipse with a circle and the small deviations that were the clues to his discovery.#

In 1611, Kepler’s son died, as did his wife. Rudolf abdicated and his successor was not supportive and so Kepler had to move with his remaining children, this time to Linz. There he advertised for and set up interviews for a new wife, “hired” one, and had six more children.

But the weirdness never ends for Kepler: In 1616, his mother was accused of witchcraft and by 1620 the charges were so serious that she was in danger of torture and execution—eight women had been executed so far. Kepler dropped everything and moved from Linz to Leonberg, more than 500 km away and essentially became her defense attorney. He won the case, but not until a year had gone by.

In 1619, amid all of the disruption that was his life, he published Harmonice Mundi (Harmonies of the World). His mission was to understand the relative periods—how long it took for a planet to orbit the sun—and see if there was any pattern. Ever the mathematical-romantic he likens their motions to musical influences— the phrase “music of the spheres” comes from Pythagoras and was a way to emphasize what he and then Plato were convinced was an overall harmony of the celestial motions. Out of this conviction of harmony, or symmetry, came what we now call Kepler’s Third Law, which we’ll talk about below. This was a crucial motivation for Newton’s gravitational theory. Kepler found a pattern that all of the planets exhibit that relates their orbital periods to the distances that they were from the Sun.

His fight with the Brahe family resulted in a settlement that required him to publish Tycho’s data. He undertook this using his own funds, and so of course the printer’s facility burned to the ground in the process.

Kepler’s ability to rebound and find work was impressive, but sometimes he made judgment mistakes. His last employer was on the wrong side of a political divide and Kepler had to set out again looking for him in order get paid. The last we see of him, he is slowly and painfully riding a horse into the rough country of continuing warfare. He never made it, dying from illness on November 15, 1630 far from home in Regensburg, Germany. His final resting place, a church graveyard, was ravaged by the Swedish army and there is no remnant of his remains. Of the 12 children that he had by his two wives, only two survived.

Kepler is considered among the greatest scientists. In 1949 Einstein considered writing a biography of him—there are many, since he was such an appealing figure. He described Kepler as one “…who had devoted himself passionately to the pursuit of deep insight into the nature of natural incidents, and who, despite all inner and outer difficulties also reached his high aim.”

“In 1930, he wrote, “In anxious and uncertain times like ours, when it is difficult to find pleasure in humanity and the course of human affairs, it is particularly consoling to think of such a supreme and quiet man as Kepler. Kepler lived in an age in which the reign of law in nature was as yet by no means certain. How great must his faith in the existence of natural law have been to give him the strength to devote decades of hard and patient work to the empirical investigation of planetary motion and the mathematical laws of that motion, entirely on his own, supported by no one and understood by very few.”

Today we would call Johannes Kepler an astrophysicist, or a theoretical astronomer. He didn’t make observations, but he used (new) mathematics—inventing additional formalisms along the way—to interpret the data and make predictions.

But we’re ahead of our current story. Let’s turn the clock all the way back to the first scientists who thought deeply about the sky and recorded their thoughts. Of course, the Greeks.

Wait. Kepler seems like a sad guy.

Glad you asked. His life was a perpetual tragedy, surrounded by an unimaginably horrid war among neighbors. There is an old, but really gripping biography of him that’s very well known and somewhat controversial that you might enjoy, Arthur Koestler’s, The Sleepwalkers. It started out as a biography of Kepler, but in later form covered the cosmology of the Greeks, Copernicus, Kepler, Brahe, through Galileo (whom he didn’t like at all).

Here’s a different look at Kepler: