14.5. The Speed of Light, Old School#

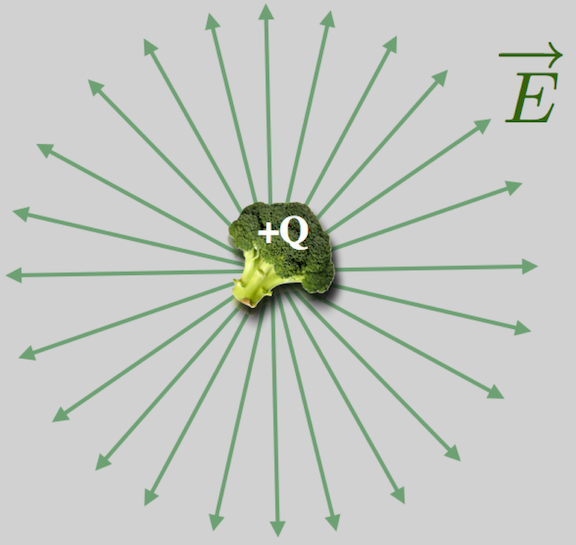

Let me remind you of two things. First there is the plain, ole’ electrostatic charge, say, positive.

Remember in Section 1 of Lesson 13 I remarked how both electrical and magnetic forces bore striking resemblences to one another and to the gravitational force. I described them generally as:

For electrical forces, this looks like:

and for magnetic forces it looks like:

(Remember, that using \(m\) for a magnetic pole is hopelessly confusing with the use of \(m\) for mass in the gravitational force equation. Fortunately, I think I can count on one hand the number of times in my life where I’ve had to actually write something involving a magnetic pole! We won’t either.) The magnetic force was most prominently observed in the force between two current-carrying wires as described by Ampere. There, that same \(k_M\) occurs.

Both \(k_M\) and \(k_E\) could be measured! And they were by Wilhelm Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch in 1855 in response to a paper that Weber wrote a decade before in which he described the combined forces between charges in a wire (the “electrodynamic” force) and a charge of an isolated electric charge (the electrostatic force). These combined forces–one electrical and the other magnetic were thought of correctly as both originating from electric sources, since a current is just electric charges in motion. Their measurement was a tour de force and Maxwell was aware of it. Weber and Kohlrausch even were able to determine that the ratio

looked like the square of a speed, but of what Weber was unable to pinpoint physically because he lacked the insight that Maxwell provided. (Weber also had a \(\sqrt{2}\) misinterpretation.)

Armand Hippolyte Louis Fizeau, a Frenchman with a very impressive name, did an incredibly impressive experiment in 1849 which measured the speed of light to be \(3.133 \times 10^8\) m/s. Pretty close to the square root of \(k_E/k_M\) above.

By the way, it is from Weber’s original paper that we get the symbol “\(c\)” for the speed of light.