18.1. A Little Bit of Minkowski#

“It came as a tremendous surprise, for in his student days Einstein had been a lazy dog… He never bothered about mathematics at all.”

The story of Hermann Minkowski is both engaging and sad. He grew up in Königsberg, Germany after some time in Russia, to a middle-class business family. His mathematical skills were apparent in high school and he entered the University of Königsberg where he stayed through his PhD degree, winning a prestigious prize at the age of 17 for a solution to a challenge problem issued in European mathematics. Mathematicians like to do that sort of thing.

In 1887 he was recruited to the University of Bonn where he taught for seven years and returned to his alma mater, the University of Königsberg, where he stayed for two years before he was appointed the chair of mathematical physics at Eidgenössische Polytechnikum Zürich in 1894. He married in 1897 and had two daughters, the second in 1902.

That was a big year for him professionally as well as David Hilbert created a chair for Minkowski at the center of European mathematics at the University of Göttingen. It was there that he developed the ideas of space and time that outlived him and set the path for a firm foundation of Special Relativity and motivated the approach to the General Theory of Relativity. This mathematization of physics was not originally welcome to Einstein, but he grew to embrace it. In fact, in some ways it was Minkowski’s style and his skill that changed the relation of physics and mathematics to the present day.

Morris Kine in a review wrote, “A key point of the [Minkowski] paper is the difference in approach to physical problems taken by mathematical physicists as opposed to theoretical physicists. In a paper published in 1908 *Minkowski reformulated Einstein’s 1905 paper by introducing the four-dimensional (space-time) non-Euclidean geometry, a step which Einstein did not think much of at the time. But more important is the attitude or philosophy that Minkowski, Hilbert, Klein, and Weyl pursued, namely, that purely mathematical considerations, including harmony and elegance of ideas, should dominate in embracing new physical facts. Mathematics so to speak was to be master and physical theory could be made to bow to the master. [my emphasis] Put otherwise, theoretical physics was a subdomain of mathematical physics, which in turn was a sub-discipline of pure mathematics.”

That Minkowski embraced the implications of Special Relativity is a delicious irony as he was Einstein’s mathematics professor in Zurich and his opinion of him was right in line with that of the other faculty:

“Oh, that Einstein, always cutting lectures… I really would not believe him capable of it.”

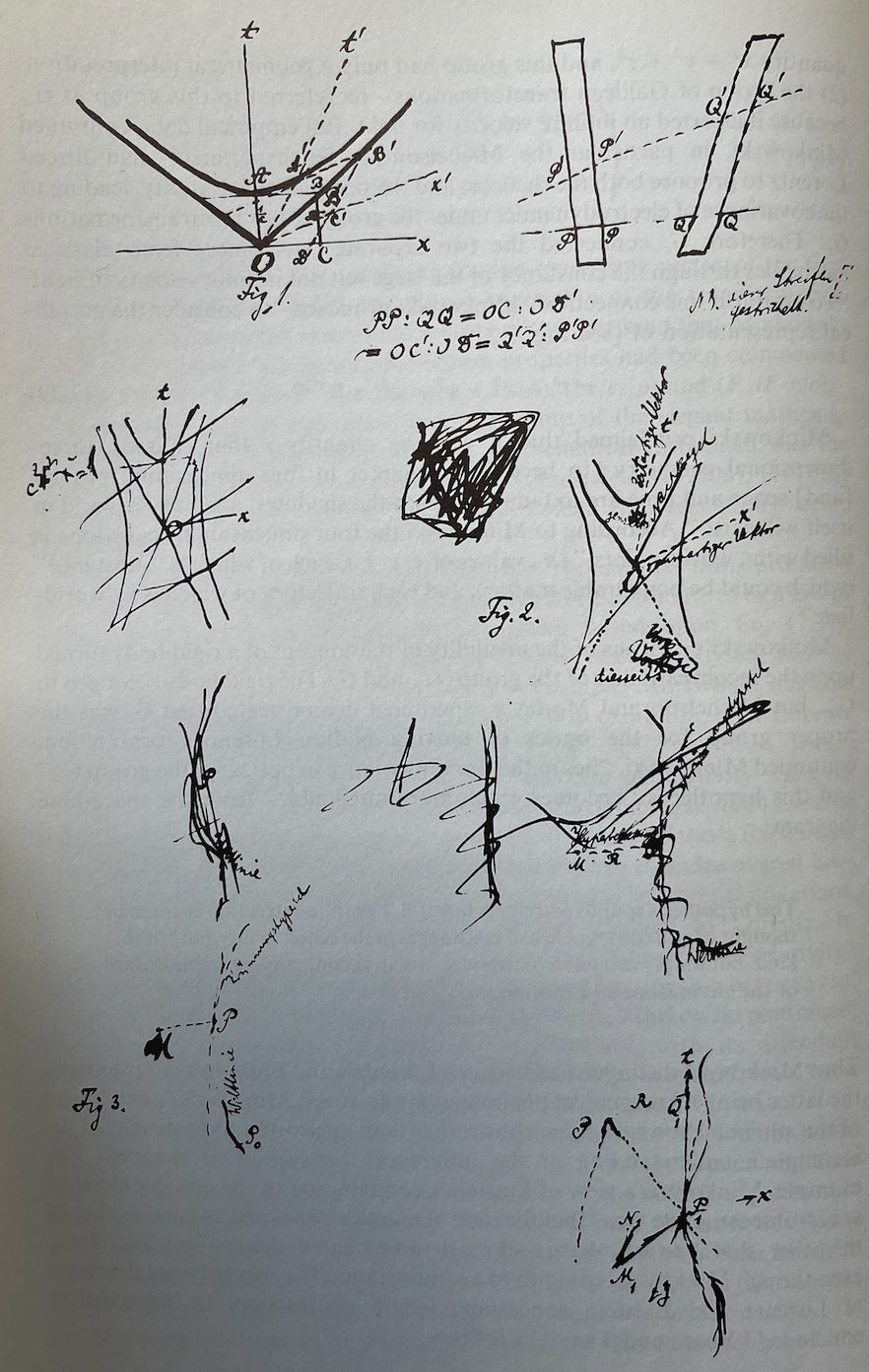

It was Minkowski who merged space and time into a single “Spacetime” continuum – a mathematical space, but importantly, a model of how the universe is really stitched together. That’s the “Spacetime” in Quarks, Spacetime, and the Big Bang. Below we’ll visit some of “Minkowski Space” and here’s a preview from his notes. Remember the plot at the top.

This work he did in 1908. While it was well-received, it was a semi-popular lecture that he gave that was the stimulus to many to take Relativity seriously. Ask Mr Google about “views of space and time” and he’ll reward you with 3.5 billion hits:

“The views of space and time which I wish to lay before you have sprung from the soil of experimental physics, and therein lies their strength. They are radical. Henceforth, space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.”

To the shock of the community and dismay to his many friends around the world, Minkowski died suddenly at the age of 44 due to a ruptured appendix.