18.5. Spacetime#

Let’s get familiar with Spacetime. My ability to draw in 4 dimensions is nil. So we’ll write only time horizontally (remember \(ct\)) and \(x\) vertically, proudly representing all three space dimensions. Stand proud, \(x\)!

18.5.1. Digging Into Spacetime#

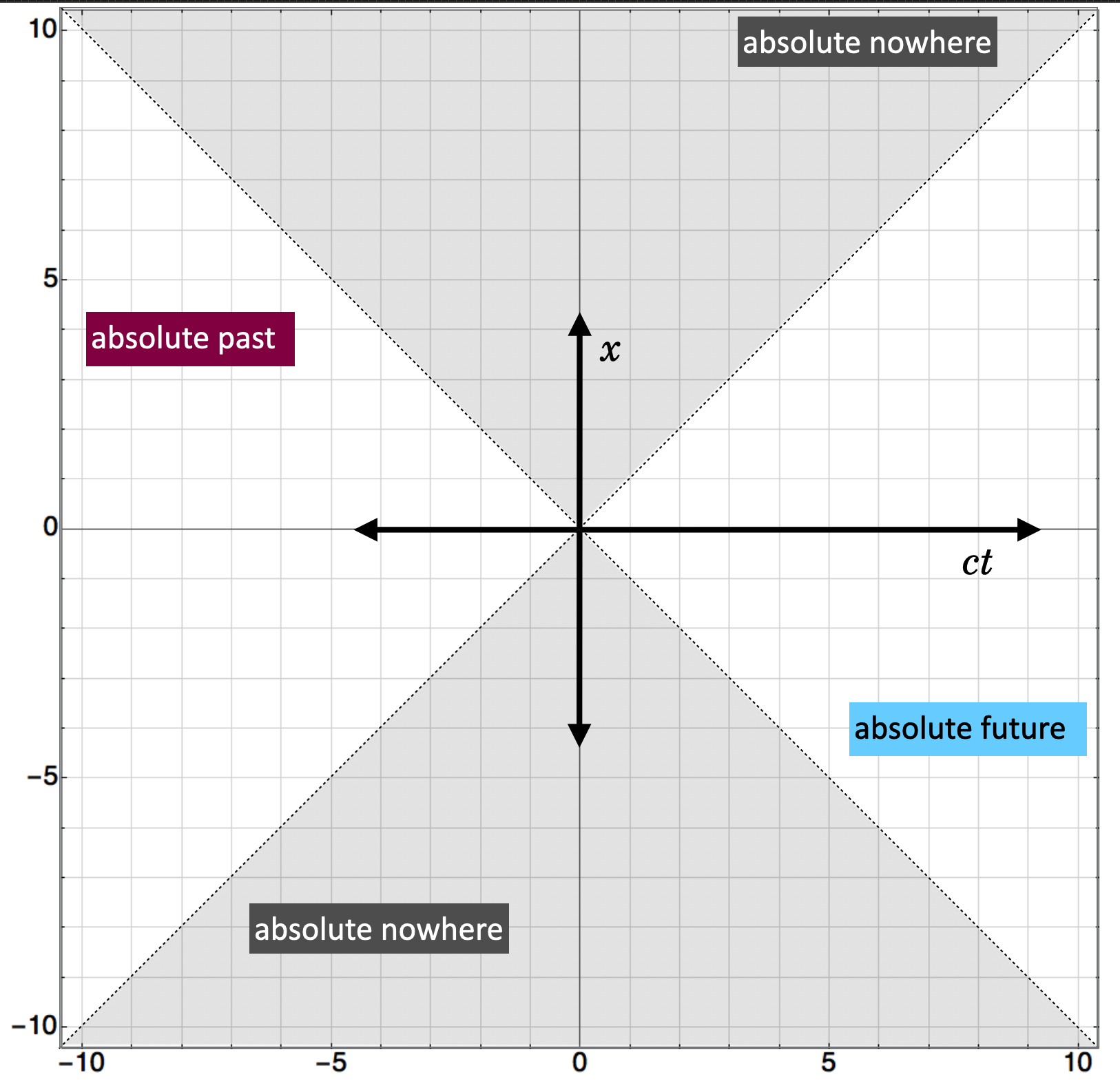

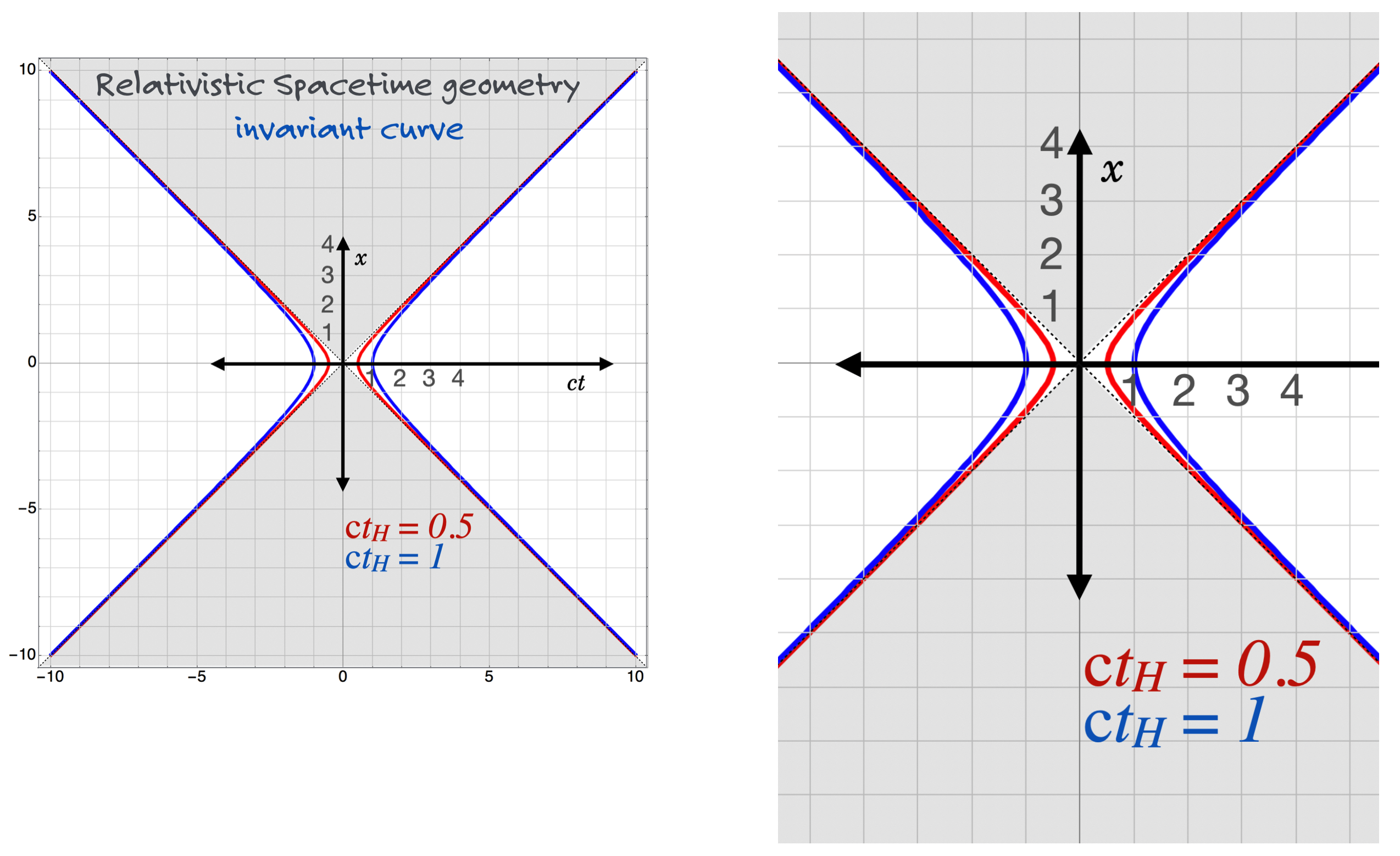

Look at this figure with time on the horizontal axis (remember, \(c \times t\) and one dimension of space on the vertical.

You’ve seen this many times. The origin of this plot is where we are right now. All frames would agree on this point as we’ve done with trains in our earlier lessons.

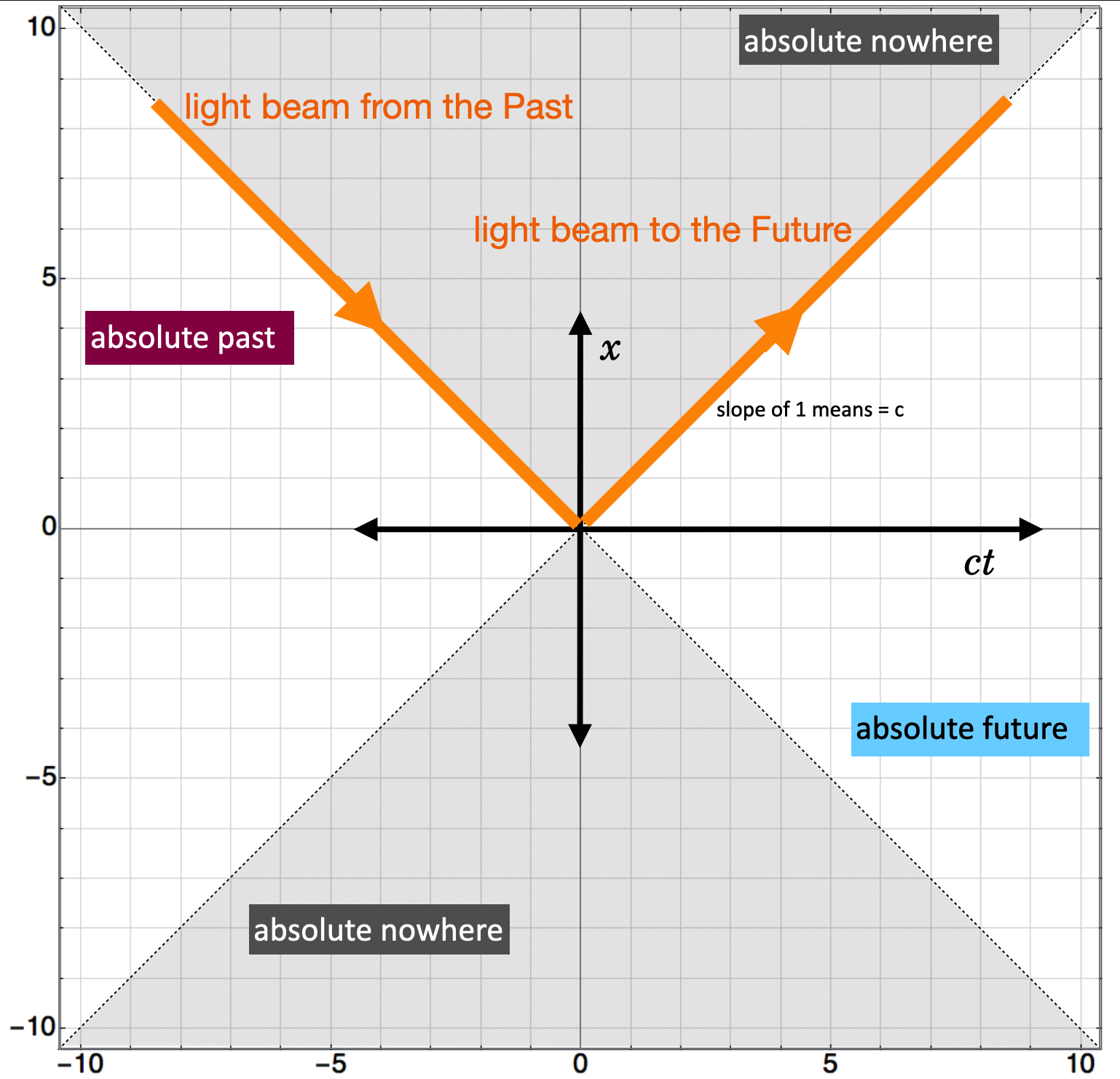

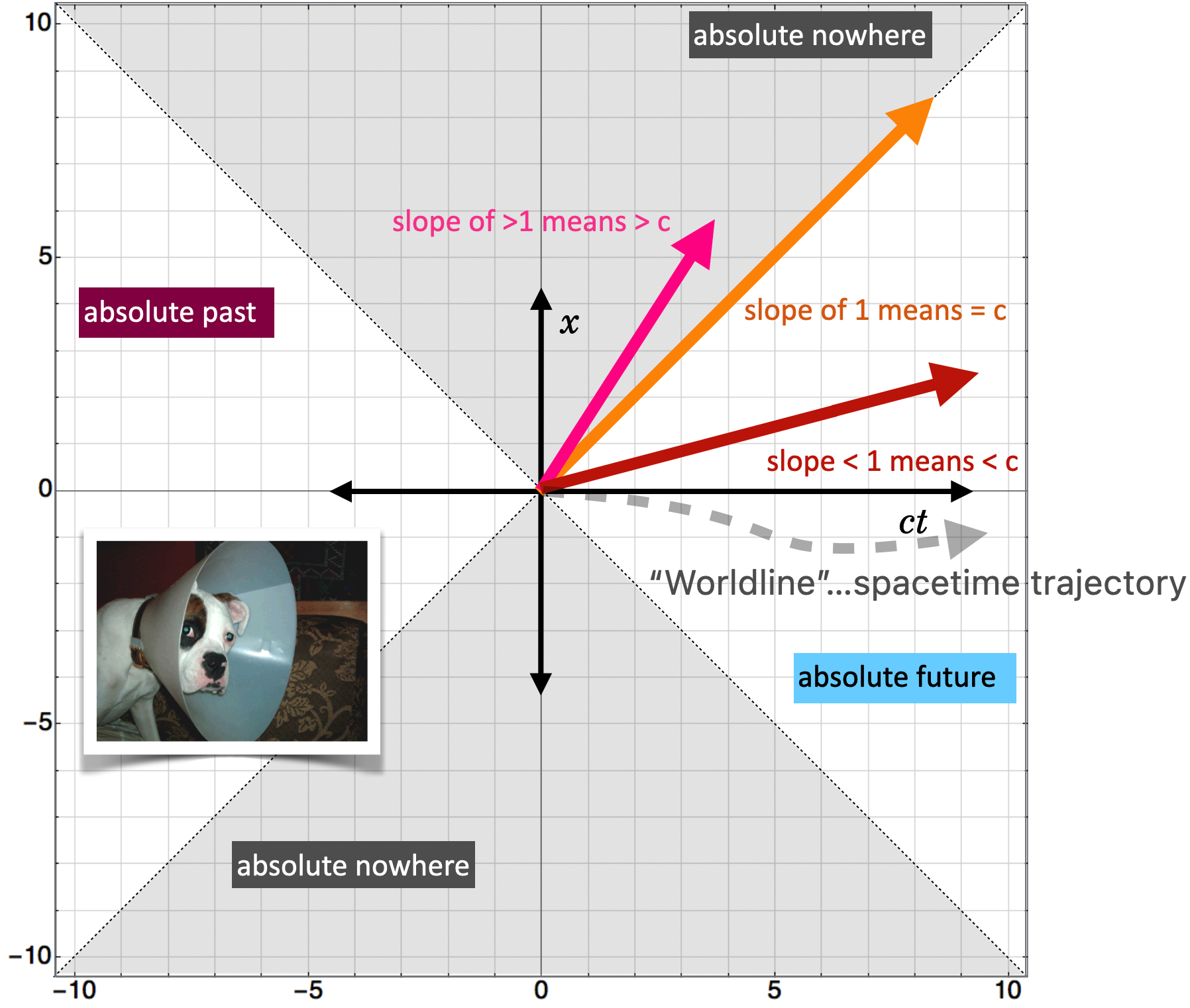

The 45º angles are important since the slope would be

So a trajectory in spacetime for an object that moves at the speed of light is 1. This is a light-like, or “light curve.” These diagonals create a multidimensional volume that looks like a cone, the Light Cone.

So, the diagonals delineate four different regions of spacetime:

In the future, where \(t>0\):

inside of the light curve are objects that leave from us at less than the speed of light. You know, normal stuff. We’d call that region the Absolute Future.

outside of the light curve are objects that leave from us at greater than the speed of light. You know, stuff of science fiction! We’d call that region the Absolute Nowhere.

In the past, where \(t<0\):

inside of the light curve are objects that move at less than the speed of light. You know, normal stuff. We’d call that region the Absolute Past.

outside of the light curve are objects that move at greater than the speed of light. You know, stuff of science fiction! We’d call that region the Absolute Nowhere.

The trajectories of all objects follow their “Worldline” which is of course inside of the light cone.

Notice one other thing about this:

Note

There are regions of spacetime at any point which are unreachable from the past – could not have influenced us – and unreachable in the future – we can not communicate with them. The universe has expanded fast enough by now that there are places in our universe with which we have no contact.

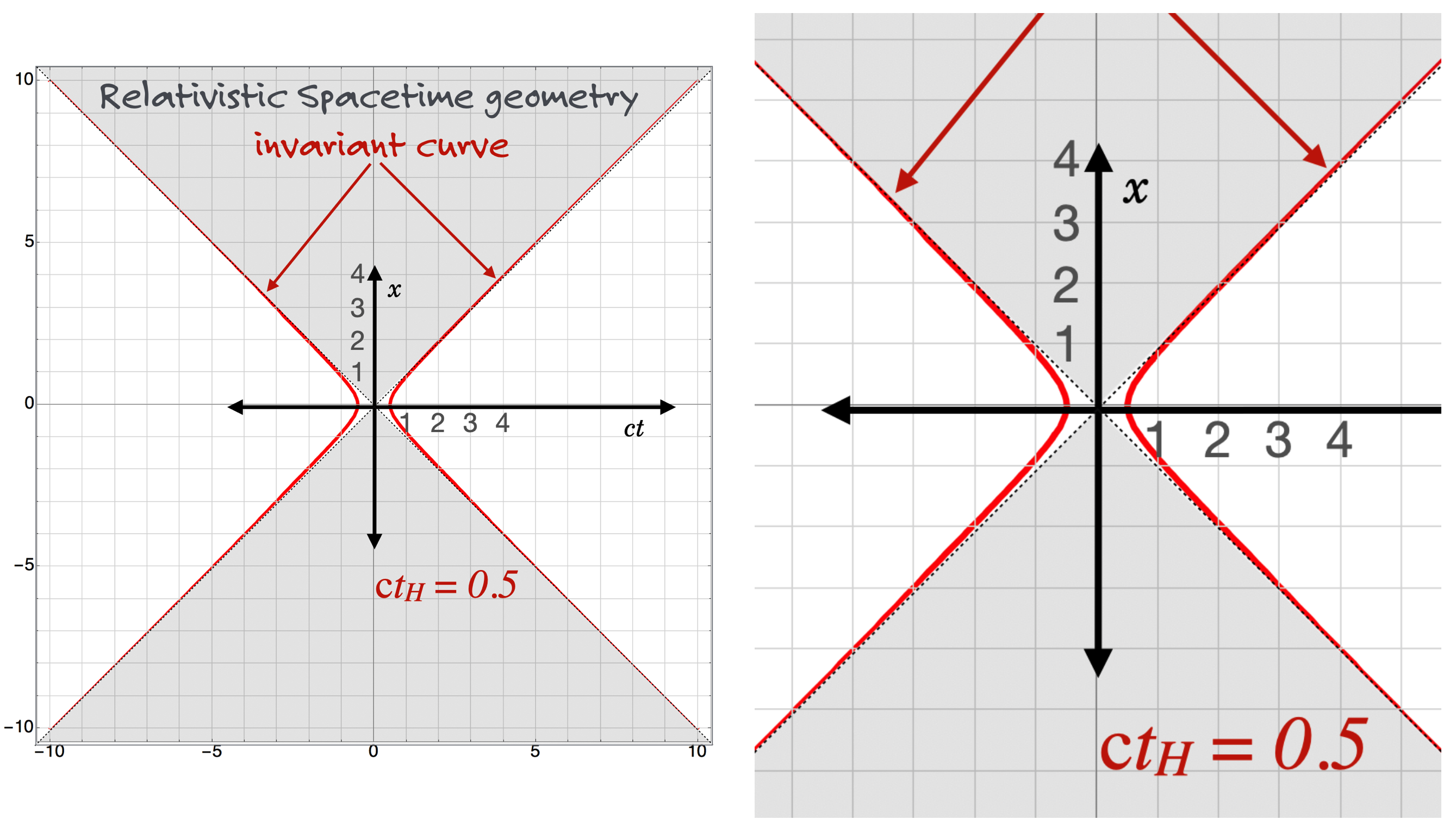

It’s inside this new space of spacetime that we now need to address the lingering question of what is the Invariant Curve for spacetime? That’s where Einstein’s frustrated university math professor enters the scene.

18.5.2. Minkowski Space#

We know that the circle will not work in Spacetime. Otherwise, we’d be seeing babies everywhere before they arrive.

What Minkowski rigorously found was that a Spacetime length is not represented by

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

but rather by:

This is not the equation of a circle! See those negative signs? Let’s make it just one dimension:

The \(H\) reminds us that we’re talking about a spacetime length in some \(A\) frame moving frame as viewed by us, \(H\), maybe lots of us moving relative to one another and that \(A\) frame. All inertial observers would agree on the length of a spacetime interval according to this formula, just like we would all agree on the length from home plate to the pitcher’s rubber in flat “regular” space.

Note

This is the equation of a hyperbola. Spacetime is hyperbolic in shape.

Let’s plot this on our spacetime diagram.

On the left in the figure is a situation for all observers of some event that happened at a time \(0.5\) units of time in the Home frame. You can see that in the blowup around the origin where for no change in \(x\) (after all, it’s in the “stationary” frame). Every point on that red curve are spacetime points that can be reached for a “proper time” of 0.5. That’s the time in the rest frame of the object that’s moving relative to all of the others. You can see that it’s 0.5 as it’s the shortest distance between the origin and the curve and where there is no change in the space dimension – a horizontal line at \(ct=0.5\) .

Now let our object move a little further (live a little longer in the Away frame), to \(ct=1\).

Here’s the counter-intuitive thing about an hyperbola. Let’s go back to the airport. The moving sidewalk has a constant speed, which we could (and did) plot on our graph as a positively sloping line. We can draw arrows on the diagram from our common point of when time starts to some time later. For the weary traveler, that line appears to be longer than it is for the couch people, but in that formula of the relativistic interval, \(\Delta s^2\) are the same for both. We’ll work that out in an example.

So, there are three important quantities that are NOT relative in Special Relativity!

The speed of light, \(c\).

The interval, \(\Delta s^2 = (c\Delta t)^2 - (\Delta x)^2\).

The “invariant mass,” \((\Delta mc^2)^2 = E_T^2 - (pc)^2\).

Even this silly equation expresses a common feature with the last two above:

It doesn’t matter what the variables are called. That the form of the equations are the same expresses a deep mathematical feature of that new kind of geometry. That’s what Minkowski found.