15.8. Frames of Reference, For Real#

Let’s think hard about something simple. What is required in order to determine motion? To measure the speed of a car for example, we could lay out a series of rulers along the side of the road and then drive the car at a constant speed while starting a clock inside the car at the beginning and stopping it at the end. If we drove past 100 meter sticks and it took 10 seconds, then we might conclude that our speed was \(v= \frac{100}{10} = 10\) m/s.

Note

Our first deep thought about ordinary things: Notice that the meter sticks were on the ground but our clock was in the car. You wouldn’t ordinarily find that a problem, right? But this is just the first of the ways that we’ll need to be very careful about what we mean when we discuss simple things.

How might we make a measurement of speed with both a clock and a meter stick in the same place? The way your car does it is by measuring how many times your (known-sized) tires turn during a given time. One trip around for a 26.1x8.9R19 tire has a diameter of 26.1 in, so a circumference of \(C=D\pi= 82\) in. So once around translates to a trip forward of 82 inches. So counting the rotations with an inside clock would be a measurement of the speed of the car using only tools within the car. (And that’s how your speedometer calculates speed. Change your tires’ sizes and you’ll mess up your speedometer and odometer.)

How about measuring speed but only using tools that are on the road? Laying out the meter sticks beforehand is simple. But what do you do about the time measurement? You’d want for a clock on the road to start at when you pass the first edge of the first meter stick and a clock to stop when you passed the last end of the last meter stick. But how do you ensure that the two clocks are calibrated with respect to one another? How might you do that?

Here’s an elaborate scheme, which is actually overblown, but something like this has to occur. Let’s set up two toy trains next to the string of meter sticks, each located at the center of the string and each pointing to one of the clocks at the ends. The toy trains’ jobs are to travel in opposite directions and start the clocks when they arrive. Then we know that they would have both been started at the same time.

Now we let them run and they have digital displays that show the seconds as they go. If the east clock says 20 seconds, then the west clock will also report 20 seconds. They’re now calibrated. Let the clocks continue to run, just counting seconds. We can be sure that they are synchronized.

Now we drive by. When we pass the east clock, we write down the time that first clock is reporting…we travel that 100 meters and then write down the time that the west clock displays. If we subtract the times, we know how much time elapsed in our 100 meter trip – using tools – meter sticks and clocks – which are all located on the road.

Notice that “on the road” is a way of saying that the clocks and the meter sticks all are stationary with respect to one another. Likewise, our tire-clock mechanism is the same way, stationary with respect to the car itself. No mixing of tools and no relative motion among the tools.

In order to make this measurement, we had to calibrate – synchronize – those two clocks.

Wait.

So, what’s the big deal? In fact, aren’t you making a simple thing too hard?

Glad you asked:

Seems like it, doesn’t it. But this clock synchronization issue becomes a critical part of Einstein’s relativity and messes with space and time forever more. Stay tuned.

The point is – apart from setting up a surprise later – is that we can completely specify motion with a meter stick and a clock. In fact, that’s going to be our definition of a Frame of Reference:

A Frame of Reference

is a system in which a length and a time can be determined from within.

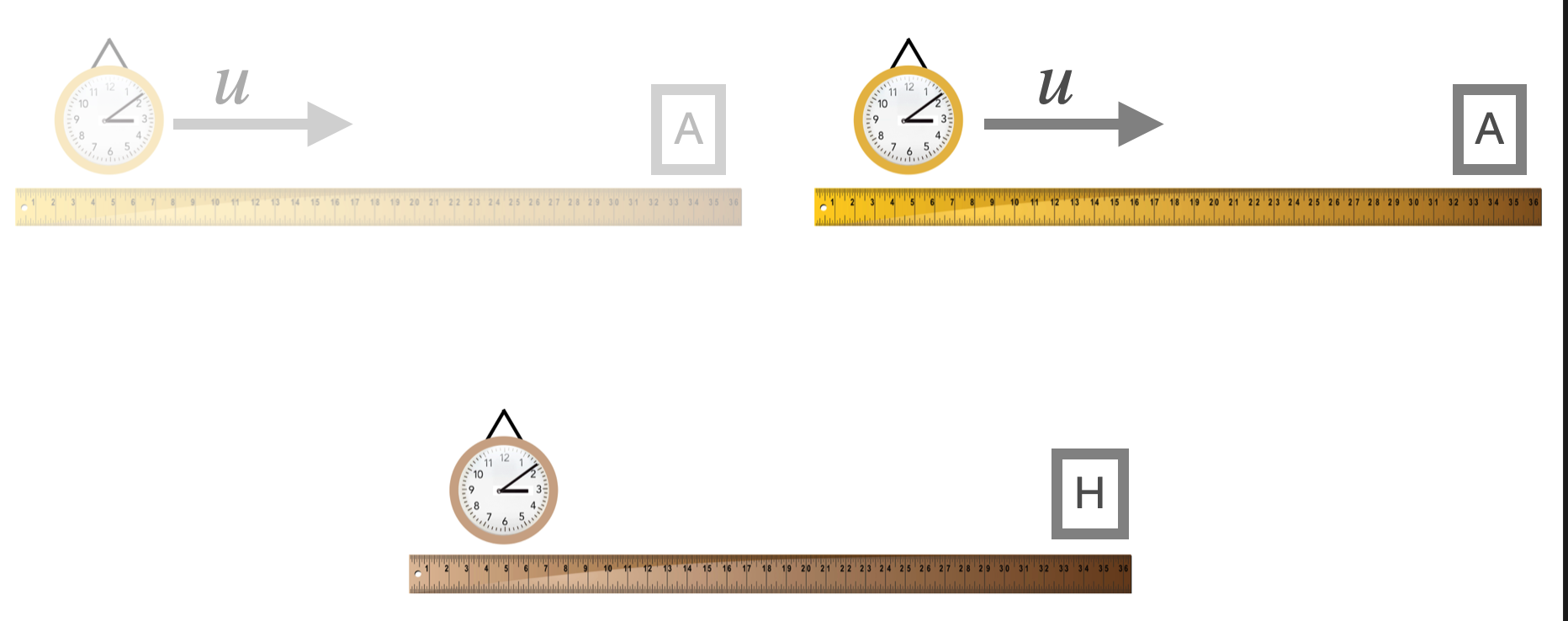

So, we think of every frame of reference as having a ruler and a clock. In fact, all objects which share a Frame of Reference are at rest with respect to one another.

An Inertial Frame of Reference

is a Frame of Reference which is not accelerated…moving at a constant velociy (which could be zero).

We will need to make reference to Frames of Reference many times and I’ll use a variety of pictures to show two frames that are moving relative to one another. They are all meant to portray the same circumstance, like cool guy and old guy here:

Please answer question 1 📺

Each guy has a coordinate system attached to them that allows for measurement in the three space directions and each of them has a watch. Cool guy appears to be in motion towards us while old guy appears to be stationary. That’s because we’re viewing them from old guy’s “reference frame.”

But what does cool guy see? In his reference frame he’s stationary and old guy is moving backwards towards him. Each of them has his own unique frame that the other doesn’t share, their Rest Frame (also called the Proper Frame):

A Rest, or Proper, Frame

is a special frame of reference in which clocks and rulers are stationary with respect to one another.

So our meter sticks and two clocks beside the road are in their own rest frame while we in the car with our clock and our tire-rotating-measuring-device are in our own rest frame.

It’s difficult to keep track and name the frames. We’ll often want to compare what goes on in one frame with another. Most books on Relativity will represent the space and time coordinates in a frame moving relative to a rest frame with primes, like \(x'\) or \(t'\). We’ll do it differently and always consistently:

Home and Away

:class: important

A rest frame we’ll call “Home,” \(H\).

Any frame moving relative to Home will be called “Away,” \(A\).

This nomenclature makes it clear who is who and so instead of \(x'\) I’ll write “\(x_A\). You’ll see.

So here’s a rather typical arrangement that we’ll see a lot.

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

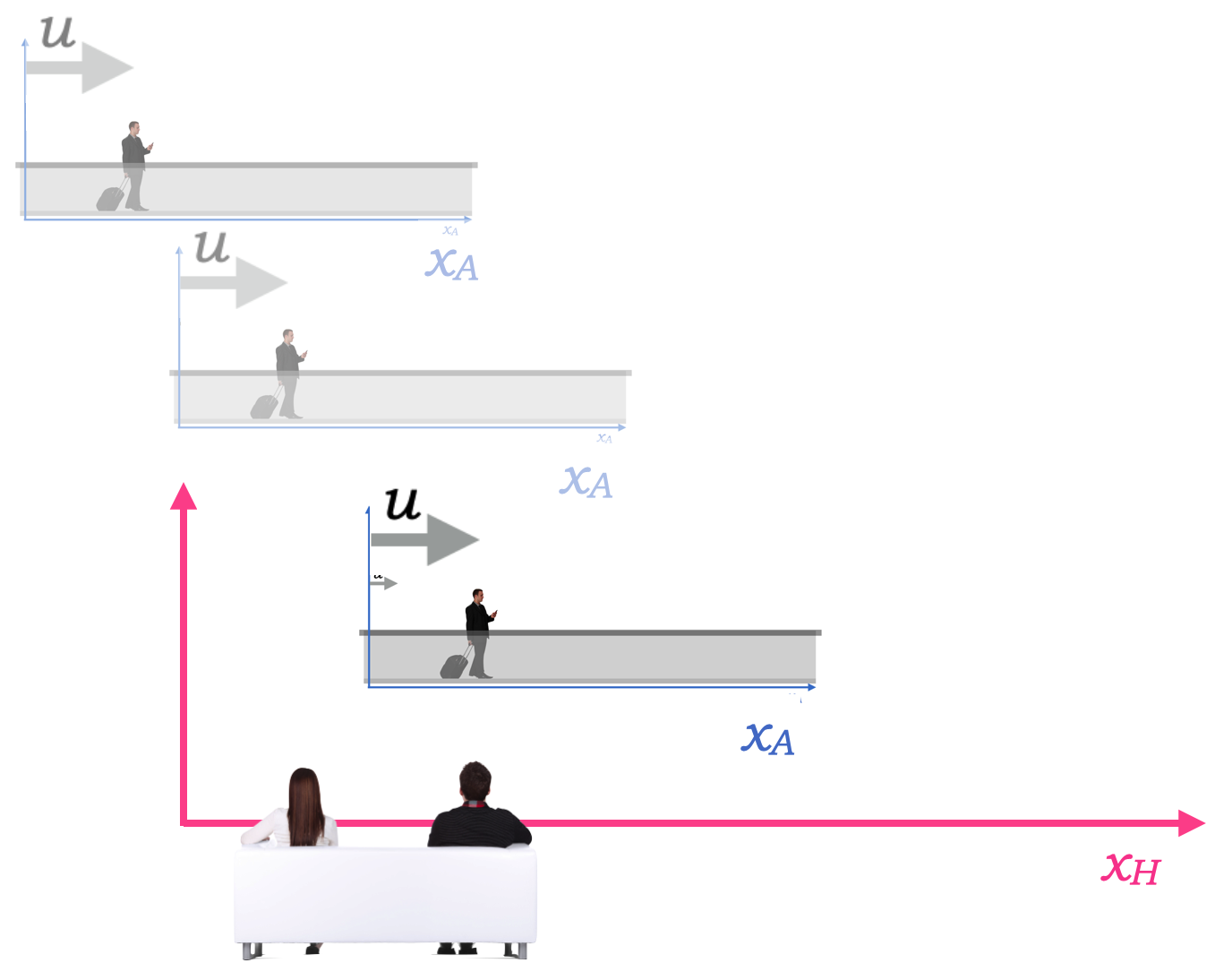

We’ll see this over and over: a Home Frame and what appears to be a relatively moving Away Frame. Each is equipped with rulers and clocks.

Above we have home – in which the picture is drawn – and away frames which we’re viewing from the Home frame (which we always would do) from which we observe an Away Frame moving past us at a speed, \(u\). I’ll always use \(u\) to represent the speed of an Away Frame (reserving \(v\) for the speed of something moving inside of the Away Frame).

One of the standard questions is to ask how things move in the Away Frame when they’re viewed from the Home Frame. You already know how to do this.

Please study example 1 🖋 📓

Let’s go to the airport.

15.8.1. Galileo And The Airport#

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

You’ve all done it. You’ve sat in the airport terminal and watched the people on the moving sidewalk. There are the people who do it right and walk on the sidewalk, and then there’s this guy. The guy who just stands on the sidewalk:

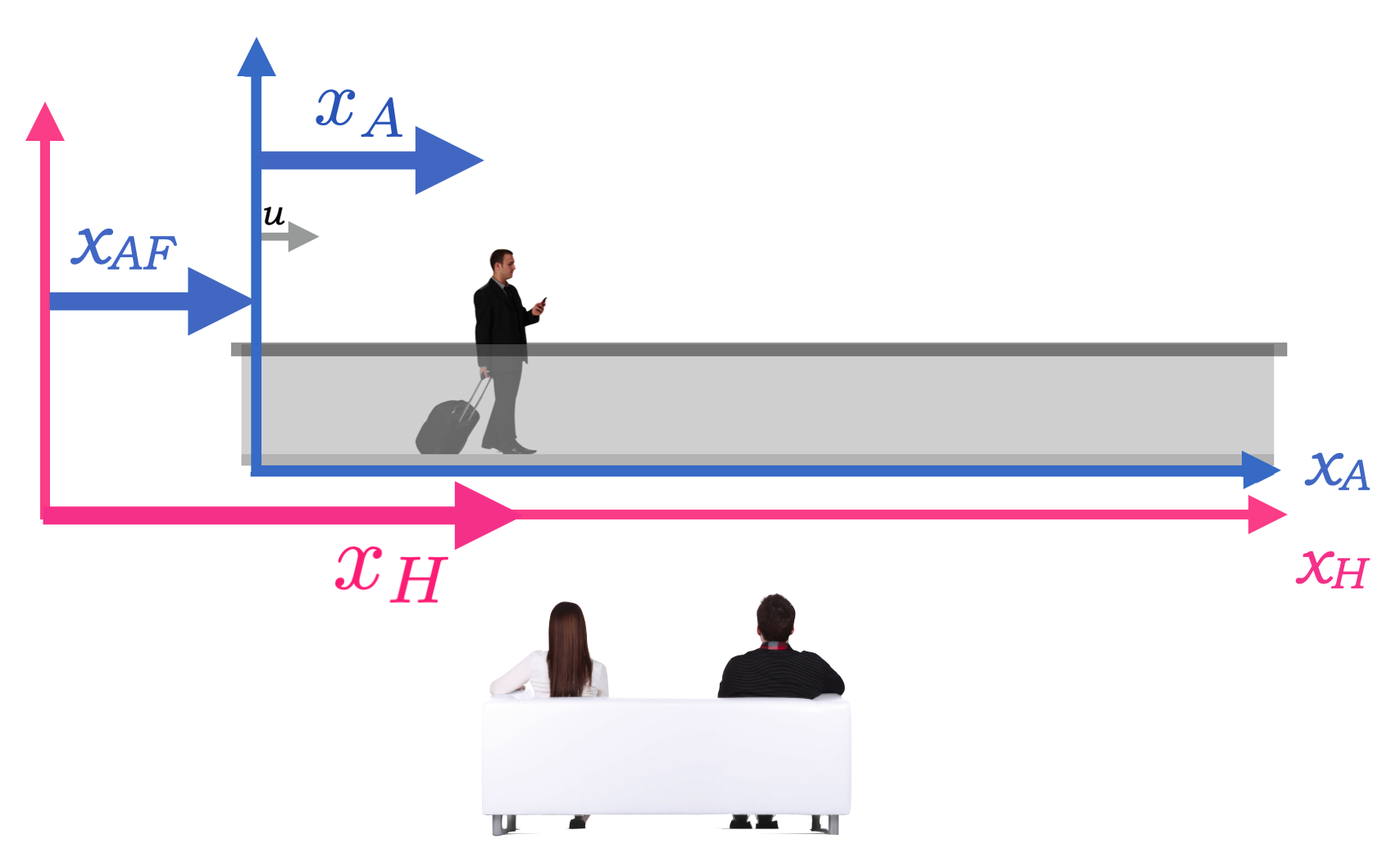

Notice that we’ve got our two frames: Couch People sitting in the terminal are occupying the Home frame while Sidewalk Guy is standing on the sidewalk looking at his phone. When the two vertical axes align, like the middle of the three scenes above, both Couch People and Sidewalk Guy start their clocks so that both have a \(t=0\) reference that’s common.

If Sidewalk Guy is 2 meters from the origin of his coordinate system (\(x_A=2\)) and if the sidewalk is moving at \(u=2\) m/s, then after 2 seconds what is the distance that Couch People would say that Sidewalk Guy is at in their coordinate system? That is, what is \(x_H\)?

Here’s the situation.

Now more quantitatively. In this figure: \(\vec{u}\) is the velocity of \(A\) relative to \(H\); \(x_A\) is the position of Sidewalk Guy relative to his coordinate system which is attached to the sidewalk with the origin as shown; \(x_{AF}\) is the position of Sidewalk Guy *relative to the airport, Couch People’s \(H\) frame.

Let’s be clear about what is what here. (You should draw this for yourself.)

\(x_{AF}\) is the distance that the origin of the Away frame has moved at any time.

\(x_A\) is the distance that Sidewalk Guy is from the origin of the Away frame. That’s constant since he’s lazy.

\(x_H\) is the distance that the Sidewalk Guy has moved as measured by the couch people in the Home frame. That changes with time.

In the Away frame, \(x_A = 2\) meters, and it’s always 2 meters since he’s not moving in his frame.

In 2 seconds, how far has the sidewalk – the whole Away frame – moved? That is, what’s \(x_{AF}\) after 2 seconds? It’s simple:

A Coordinate Transformation

is transforming, or calculating, the coordinates of an event that occurs in one Frame of Reference into another Frame of Reference.

What we just did is calculate a Galilean Transformation, represented by the simple model:

So what is \(x_H\)? It’s

Note

What Galilean Relativity says is that no mechanical experiment can tell you that you’re moving or not moving at a constant velocity.

What that means in detail is that the equations that describe a mechanical process in one frame will be the same equations that describe that process in another inertial frame. So the equations that would describe a ball rolling down a ramp, or a pendulum, or tossing a baseball as described by someone in the Away frame would be the same equations as those watching from the Home frame.

Even more specifically: if you were to take the equations in the Away frame and substitute the variables from the above equation, reversed:

You’d get an equation now in terms of \(x_H\) and the \(u\) would drop out…except for the subscript \(H\) the two equations would be identical.

Please study example 2 🖋 📓

Please answer question 2 📺

Please answer question 3 📺

15.8.2. Coordinate Transformations#

This sort of going from one frame of reference to another is a regular feature of relativity and other areas of physics. In general, what it always means is:

We will start with known coordinates in the Away frame and then a “transformation” among those \(x_A\) and \(t_A\) converts them into those variables measured in the Home frame. Or, the other way around. That transformation is just a formula, and in this case it’s the simple:

Notice that this is just like the constant speed definition from Lesson XX and the reason that’s the case is that the time, \(t\) is just a common parameter. We could plot our airport adventure easily, which is another way of solving that simple equation.

Note

Boy, is that going to change.

15.8.3. Coordinate Transformations Inside of Other Models of Motion#

We can imagine other kinds of transformations. Look at Newton’s second law:

The quantity in the brackets is of course the speed, and the operation in front of the brackets is asking for the change of that quantity with respect to time, which is of course the acceleration.

If we were to replace the A frame variables with those transformed by the Galilean transformation, we would get:

It looks the same, except the subscript is different. That “form independence” is the hallmark of a model that doesn’t care about some transformation done on it.

Here it is: If one were to substitute as above:

Since \(u\) doesn’t change in time, any change of \(u\) with respect to \(t\) drops out and the final result for \(F_H\) has exactly the same form as \(F_A\). This “form independence” is important and signals that an “invariance” has been discovered. We could call the variables Sally and Bill instead of \(x_A\) and \(x_H\)…it doesn’t matter. What matters is the algebraic form of the equations.

So, mechanical equations of motion do not care about relative inertial motion. Said a fancier way: Mechanics is invariant with respect to a Galilean Transformation.

So:

Maxwell seems to fail,

Newton seems to be okay,

when comparing electromagnetic and mechanical phenomena between inertially moving frames of reference. Hold onto your hat.

You’ll never be the same in airports again.