14.1. A Little Bit of Maxwell#

Dafty. That was his nickname as a kid at the Edinburgh Academy when he entered at the age of 10.

By the age of 14 he published his first mathematical paper on a generalization of an ellipse to include “ovals.” His construction involved both a mathematical analysis and a physical model to draw the curves. This connection of the abstract and the concrete would reappear throughout his career. It was the first of three papers that he presented to the Royal Academy of Scotland…none of which were accepted for publication since the editors would not believe that someone so young could have actually done that work. He’d also published poetry before going to the university when he was 16 years old. Not ordinary.

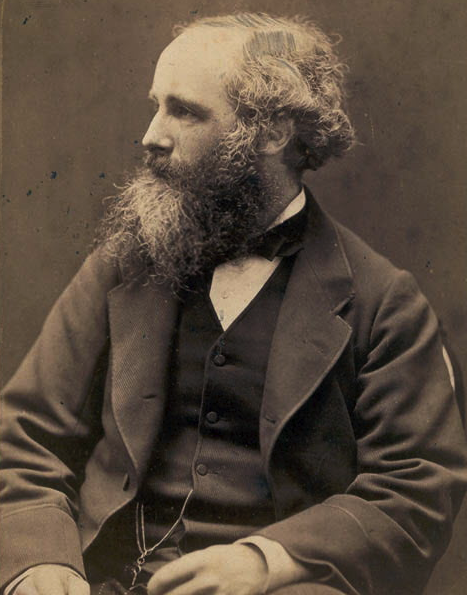

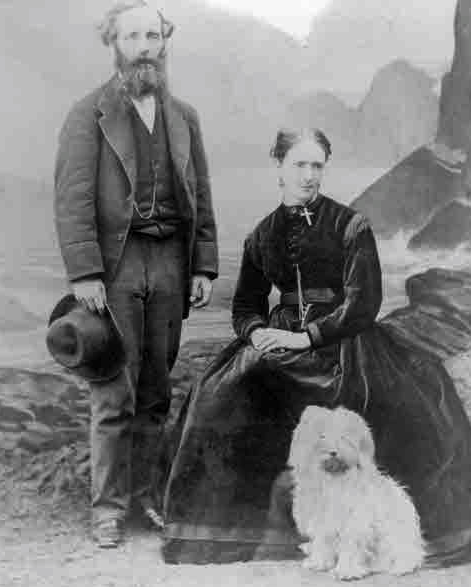

Fig. 14.1 After finishing his degree at the University of Edinburgh, he studied at Trinity College, Cambridge (Newton’s former home-base), graduating in 1854 at the age of 23. By the time he was 25 years old he held the chair of Natural Philosophy (“physics” in those days) at Marischal College in Aberdeen. That’s when he fixed Saturn and married Katherine Mary Dewar, daughter of the head of the college. They were childless, but their marriage was described later as, “married life…of unexampled devotion.”#

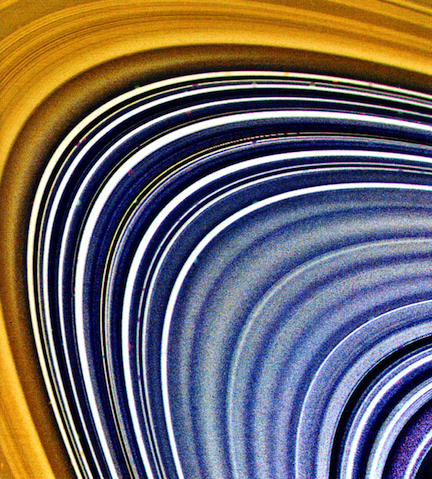

A major prize was announced to explain why Saturn’s rings were stable. If they were solid, they should have broken apart. It took him two years to show that stability could only be achieved if the rings consisted of millions of small solid particles. They would all move together and clump in the way visible from a telescope…and only truly confirmed by the Voyager spacecraft in its Saturn fly-by in 1980. It’s now believed that the debris is left over from some moon of the planet that was broken up either through collision or enormous tidal forces. Said an examiner at the time of Maxwell’s submission, “It is one of the most remarkable applications of mathematics to physics that I have ever seen.”

Calculate it:

Oh. He also did experiments to show that white light would result from the mixture of red, green, and blue light (aka “RGB”)—the principle that you’re likely experiencing on whatever computer display (CRT, LCD, OLED) you’re using to read this document.

Shy Guy

“At school he was at first regarded as shy and rather dull. he made no friendships and spent his occasional holidays in reading old ballads, drawing curious diagrams and making rude mechanical models. This absorption in such pursuits, totally unintelligible to his schoolfellows, who were then totally ignorant of mathematics, procured him a not very complimentary nickname. About the middle of his school career however he surprised his companions by suddenly becoming one of the most brilliant among them, gaining prizes and sometimes the highest prizes for scholarship, mathematics, and English verse.” as remembered by James Tait, a classmate and friend…and a pioneer of mathematical physics.

He and Katherine moved to London in 1860 where he assumed the chair of Natural Philosophy at King’s College. During the six years he was there he did his most important work on electromagnetic theory, the subject of this lesson. He had read Faraday’s notebooks around 1855 and corresponded with the grand old man. But nobody anticipated what he’d do with Faraday’s ideas. While he was in London, he finally met Faraday. It’s quite pleasing to think about the 30 year old Maxwell and the 70 year old Faraday enjoying one another’s companionship and mutual respect.

In 1862 he wrote, “We can scarcely avoid the conclusion that light consists in the transverse undulations of the same medium which is the cause of electric and magnetic phenomena.” And in 1873 he wrote up his research in this area which was the enunciation of the four, fundamental Maxwell’s Equations that put everything together and form the basis of modern physics and relativity theory. It is a high-altitude summary of this work that interests us in this lesson.

Not content with his revolutionizing light and electromagnetism, he laid the foundations for the statistical basis of modern thermodynamics—what we call Maxwell-Boltzman theory today. He reluctantly found himself in the Chair at Cambridge University where he was the first Cavendish Professor of Physics in 1871. He designed the Cavendish Laboratory—in which we’ll see as the home of many 20th century milestones in the 20th century.

Unconscionably he became deadly ill with an abdominal cancer and died at the age of 48 in 1879. James Clerk Maxwell is always regarded as among the class of Newton and Einstein. Einstein wrote of Maxwell:

“[This work was the] most profound and the most fruitful that physics has experienced since the time of Newton.”

That he was as funny and companionable, as well as considerate as a supervisor rounds out a picture of one of the Big Three as being the most normal and highest quality individual among them. In these ways, he was perfectly matched for collaboration with Faraday, about whom nobody would say unpleasant things either—except about his presumed atrocious ideas. James Maxwell was indeed, Michael Faraday’s hero.

Let’s oscillate.