9.4. Putting the Sun Where It (almost) Belongs: Copernicus#

Please answer Question 2 for points:

Please answer Question 2 for points:

Please answer Question 4 for points:

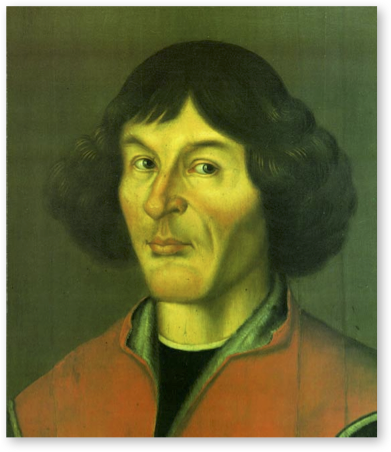

The Renaissance and the rise of humanism brought with them a freedom of thinking. Universities began to flourish, especially in Italy, Paris, and Oxford. A century before Galileo joined the faculty at Padua, an unassuming Pole also went to Padua to study medicine, for which it was particularly renowned, but similarly to Galileo, he couldn’t shake his fascination for mathematics and astronomy. Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) was sent to Italy by his uncle who was the Bishop of Warmia to study canon law at Bologna but he actually studied in Padua, Rome, Bologna, and Ferrara. While in Bologna, he lived with the faculty astronomer and made many observations with him. (The primary job of a late medieval astronomy professor included teaching mathematics and astrology.) He eventually went on to Padua to study medicine and believe it or not, astrology was an important tool for doctors and so Copernicus was well-prepared. While he obviously had trouble “declaring a major” he did manage to receive his canon law doctorate degree and have sufficient training in medicine that he would be a practicing physician and personal assistant to his uncle for the rest of his benefactor’s life.

Fig. 9.10 Nicolaus Copernicus 1473-1543#

Copernicus never took vows and so was a lifelong lay-clergyman. He took a mistress and his hobby: was astronomy. He had learned Greek in Italy and slowly began to question the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic pictures, being especially irritated with Ptolemy’s use of the equant, believing that it destroyed the symmetry. He knew of Aristarcus and began to think differently.

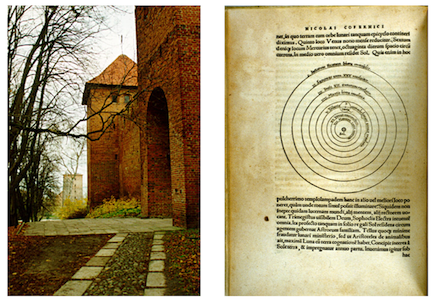

What intrigued him was that the order of the planets was arbitrary in the Ptolemaic system—he thought there should be some correlation of motion with the positions of the planets. In the figure above depicting the Aristotelean universe the planets ordering was Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Saturn, Jupiter, and the stars. Sometimes people put Venus closer to Earth. What he knew however was that the years of each planet were ordered and perhaps the Humanist fascination with the Sun rubbed off on him a little. In any case, he made a stab at suggesting a Sun-centered picture with the planets in the order that we know them now, following the lengths of the years of each as one gets further away from the Sun. His little attempt was written some time before 1514 and distributed to friends and called Nicolai Copernici de hypothesibus motuum caelestium a se constitutis commentariolus, a “little commentary,” or Commentariolus. In it he lays out his plans in about 40 pages, but not logic. It made it to Rome and and it’s known that Pope Clement VII heard a lecture on it 20 years after its production and was intrigued. It listed Copernicus’ objections and a set of assumptions: basically, the Sun is stationary, the Earth moves around it annually, the Earth rotates on its own axis daily, and that retrograde motion is a natural consequence of the relative orbit of Earth and the other planets.

Fig. 9.11 On the left is the medieval tower in cold, marshy northern Frauenburg on the Baltic Sea in Prussia (Poland) where Copernicus wrote his famous book. On the right is the picture that everyone thinks of when they think “Copernicus”…except it’s not quite so simple.#

This went okay and high ranking clergy even offered to support him in the production of a more complete book. But there was enough criticism and it seems that Copernicus had thin skin and he waited almost 40 years to write the complete story: De revolutionibus orbium celestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Orbs (orbits)…the densest treatise on spherical geometry, maybe ever.

He came to produce Revolutionibus somewhat reluctantly. It took decades. It seems he required an odd companion.