7.8. Algebra by Thermometers!#

When you use equations for a living, after a while they take on visual properties that you learn to rely on. They speak to me like a second language might to you. But when you don’t use equations for a living, I still think that the same kind of physical insight can be gained by continuing to construct geometric diagrams that do the job solving the equations of physical models. This is really useful when we begin to consider conservation of momentum and other conserved quantities that we’ll discover. Let’s quickly look at the stop shot using areas and then we’ll “graduate” to a more straightforward approach: “thermometers.”

7.8.1. Momentum as thermometers#

We can solve the momentum conservation equations graphically by eye-balling lengths of what I’ll call “thermometer graphs.”

The lengths of the “thermometers” are momentum and the directions matter: up is a positive momentum and down is a negative momentum (which implies that we’ve chosen a direction in space to represent positive and negative). For our simple stop-shot, the situation is pretty straightforward:

Pens out!

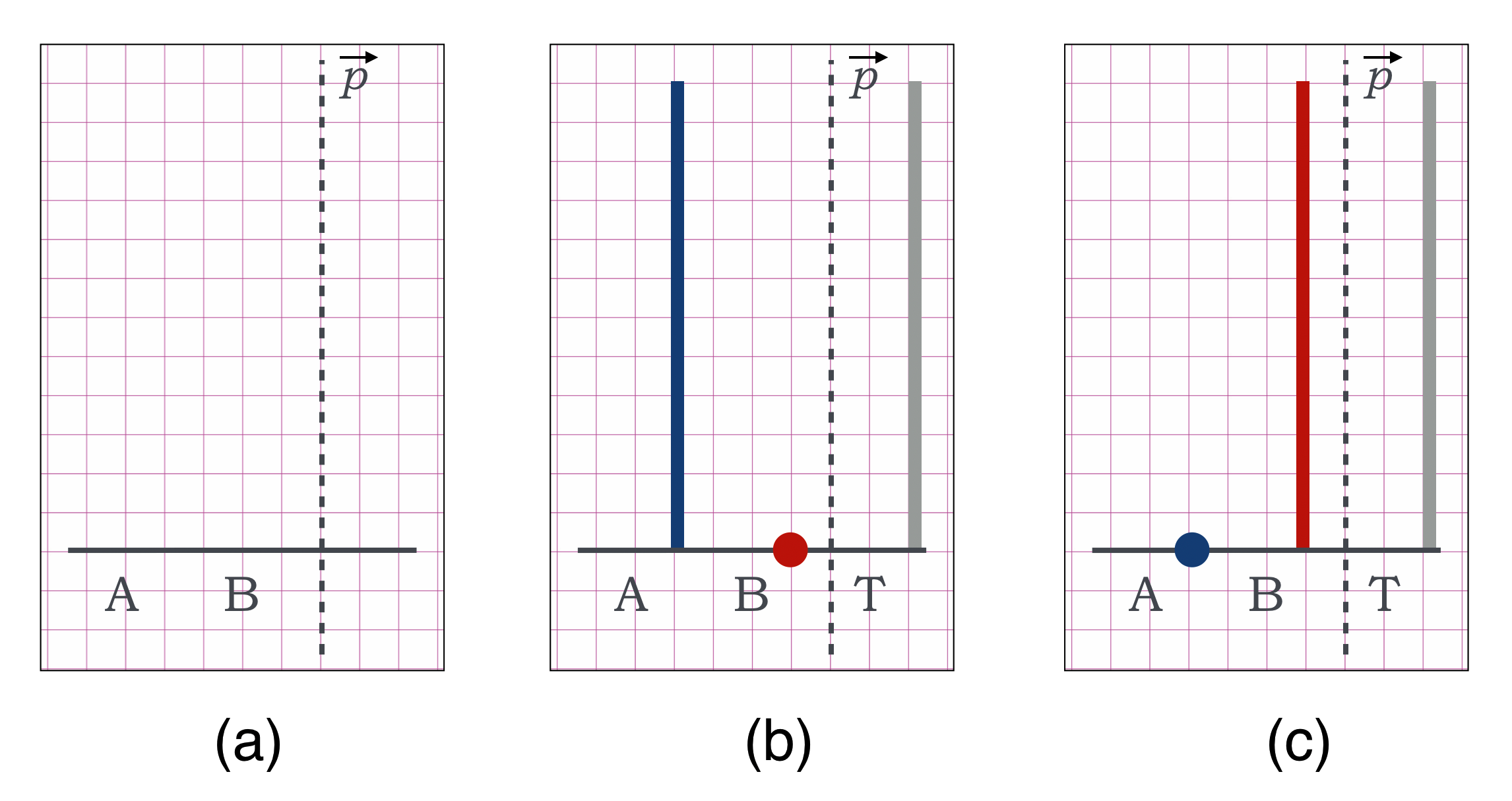

Fig. 7.20 (a) shows the momentum-thermometer axes. Here \(T\) means the total momentum and \(A\) and \(B\) are placeholders where lines will be drawn to represent the momentum values. The \(\vec{p}\) axis can be positive and negative depending on the kind of collision. (b) shows the momenta added for the initial situation and (c) for the final situation.#

\((a)\) sets up the working areas of the thermometer diagram. The vertical units are those of momentum. The horizontal positions just label the players (on the left) and the momentum tally (on the right). Here’s how I would reason this through.

On the left of the vertical dashed separator line, I plot the momenta of each of the colliding particles. \(A\) had momentum 12 and \(B\) had momentum zero.

Then I tally up the total momentum of the particles in the initial state and record them in a momentum thermometer on the right of the dividing line labeled “\(T\)” for Total.

Then I construct the final situation where now I’m guided by the Total momentum, right hand thermometer as the final \(A\) and \(B\) thermometers have to add to that \(T\) value.

\((c)\) is the result. The situation already gave us the answer since we saw it in the movie: the final momentum of \(A\) is zero (stops dead) and since its momentum and \(B\)’s final momentum must add to that right hand \(T\) momentum, we must assign the \(B\) thermometer to be 12.

This is a simple problem, but a more complex problem might lead you to make a prediction based on preserving that right hand \(T\) total.

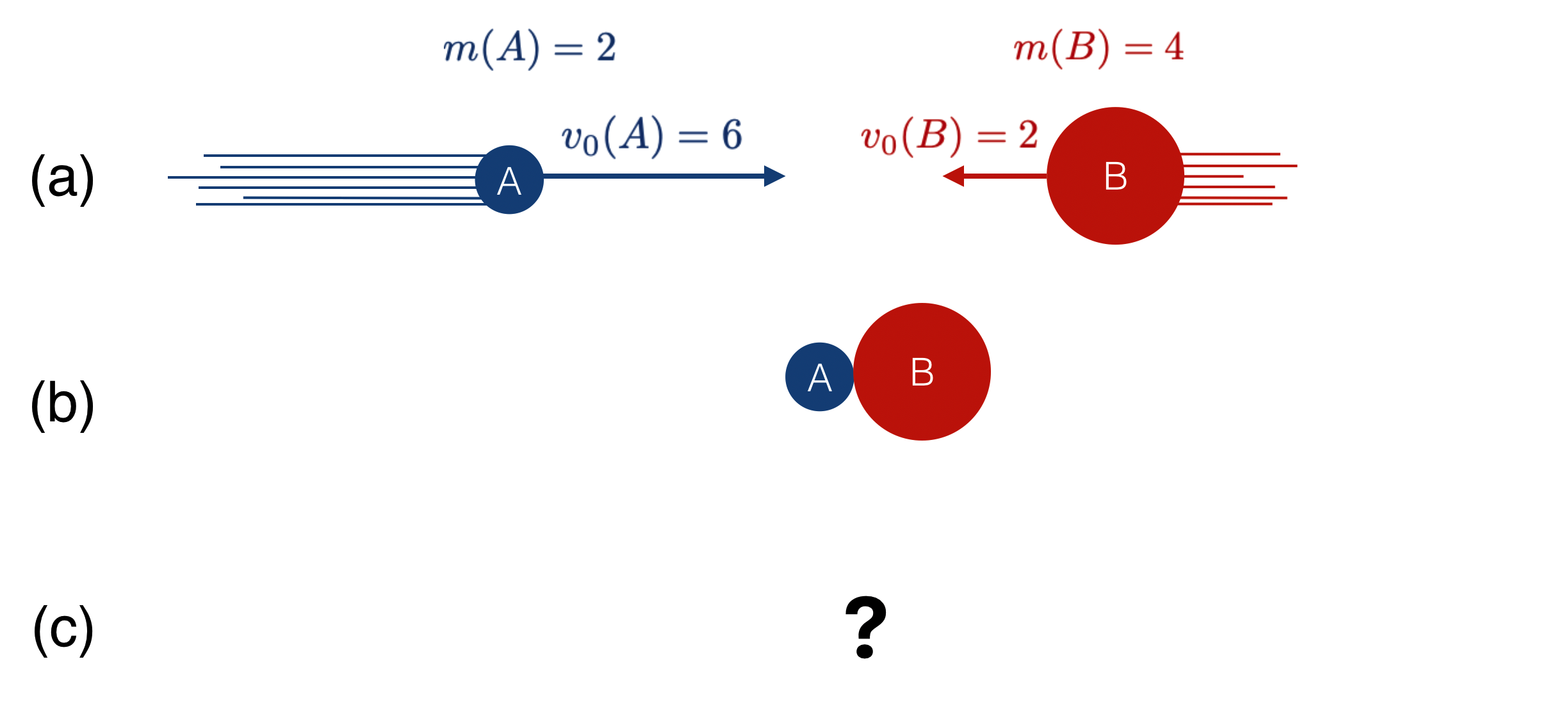

Let’s do one more. The stop shot example was intentionally simple and I appealed to your experience (and a video) to tell you the result. Here’s a different situation: we’ve got a small guy moving fast, colliding, and bouncing off a large guy moving slower. Sounds like football. Let’s conserve momentum for this collision:

Fig. 7.21 Our collision…what happens if they perfectly recoil from one another?#

Please study Example 3:

This is enough to take it our for a spin on your own:

Please answer Question 4 for points:

Please answer Question 5 for points:

Please answer Question 6 for points: